Star Trek: Discovery Is Smart-Sounding Scientific Nonsense, Season 1, Episode 4 Recap

IFLS might be fun for the armchair enthusiast, but couldn’t you have at least consulted an expert?

“You were always a good officer. Until you weren’t.”

–Saru, from Star Trek: Discovery

With a captured killer alien on board, a Federation colony about to be destroyed by the Klingons, and a Captain and crew unafraid to break the rules to succeed at their mission, the latest Star Trek: Discovery episode, ‘The Butcher’s Knife Cares Not for the Lamb’s Cry,’ has all the ingredients needed for a masterpiece. Yet quite shockingly, we wound up with the worst episode of Star Trek: Discovery yet. The actions of many characters are reckless and nonsensical. The science is superficial and gallingly at odds with what we already know. And in a show that’s still searching for its moral compass, the closest thing we get to an ethical statement comes from the first officer, Saru, who can only uselessly point out the hypocrisy of Burnham and the rest of Discovery’s crew.

Recap: 6 months after the death of her former captain, Burnham is struggling with the aftermath, and gets a delivery she refuses to open: the last will and testament of Georgiou. Meanwhile, Captain Lorca is preparing for the darkness that war brings, running battle simulations and using the captured creature from last episode as a potential secret weapon. Back on Discovery, Commander Landry names the secret space creature “Ripper,” and prepares to test its capabilities as a weapon. We learn more about Science Officer Stamets’ technology that killed the crew of the USS Glenn: the capability of “jumping” from one star system to the next. We also learn what really killed everyone aboard the Glenn, “the Glenn crashed into an undetectable Hawking Radiation firewall.” (More on that later.) If only they had a supercomputer, they could solve the problem. But instead, all they have is a mystery device they found on the Glenn that appears to be missing a part. The mystery device, by the way, looks exactly like a chair.

Over 80 light-years away, a Federation base that controls a large amount of dilithium is under Klingon attack. They have no defense, and will fall in a matter of hours. Discovery is the closest ship, and only the “jump” technology could get there in time. They go to Black Alert, attempt to jump towards their destination, but wind up somewhere else. Without that “extra computational power” they can’t control the jump destination well enough. But Burnham notices that the mystery creature was behaving curiously during the jump; do you think perhaps the mysterious creature aboard the Glenn, the chair-looking device missing a component, and the need for navigational/computational power could be related? Commander Landry doesn’t, and doubles down on treating “Ripper” like nothing but a weapon, despite evidence to the contrary right in front of her face.

Some of the crew loses their appetite for this war and threatens to pick up their toys and go home, but Captain Lorca plays the audio of Federation members dying in Klingon attacks. This sways Stamets to stay, but also sways Landry towards extraordinary hubris: a one-on-one fight against the mystery creature with no security measures. When she dies, you feel like giving her a Darwin award for her arrogant, suicidal stupidity. Burnham invites Saru under false pretense of an apology to use his threat-sensing ganglia to see if the creature is hostile towards non-threatening creatures. It isn’t, but Saru sees through Burnham’s utilitarian and insincere ruse; she is unapologetic. A bit later, she befriends “Ripper” by offering it the special fungus spores from Stamets’ lab. (Apparently, breaking and entering and stealing is par for the course aboard the Discovery.)

Burnham puts the pieces together than no one else can: the tardigrade-like “Ripper” sees the spores as a symbiotic energy source, and gets to talk with the mushrooms. Since they’re spread throughout space in some sort of galactic network, they see the possibility of putting the pieces together: chair + creature + computer + mycological spores = the ability to navigate where you jump. They transport Ripper into the chamber with the chair, and it instantly works; they have a perfect map of everything in between them and their destination, and they can jump exactly where they want. They arrive in the nick of time as the Federation colony’s shields fail; they bomb them all as they jump away, leaving the Klingon ships destroyed. They don’t rescue the people from the Federation base, despite the fact that there are no other Federation ships close by; guess they’ll get destroyed next episode. Burnham apologizes to “Ripper,” gets talked at by Lilly, and then listens to Georgiou’s message and receives a gift that’s a callback to the premiere: an old optical telescope.

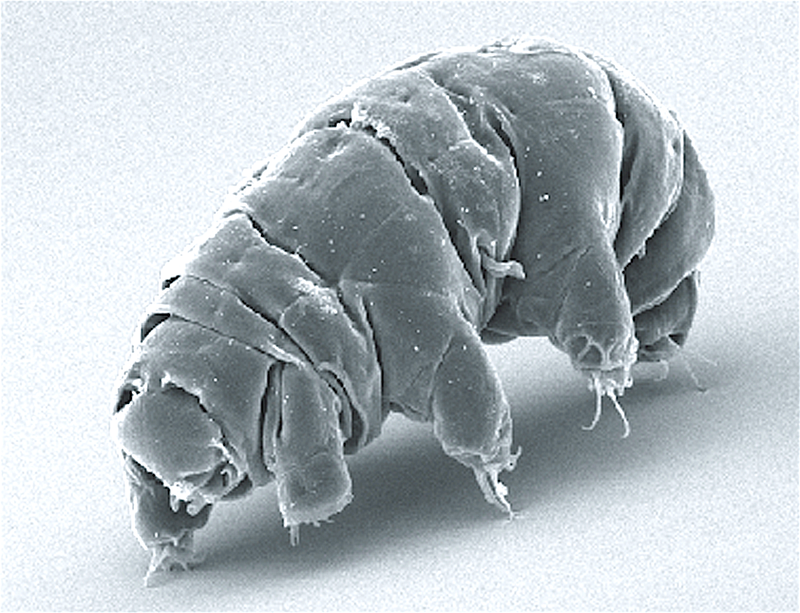

Science: There are a few moments that stand out in terms of science in this episode. The first is the tardigrade-like nature of “Ripper,” the mysterious creature aboard the Discovery. They created a bear-sized creature with a tardigrade-like proboscis/mouth, which moves quickly, leeches energy from fungal spores, and travels through space. If you’ve followed non-scientific (but science enthusiast) sites on the internet like IFLS over the years, you’ve likely seen pictures of tardigrades: microscopic water-bears. If you’ve looked beyond that surface-level stuff, you’ll have learned a few actual facts about the physiology and behavior of tardigrades:

- they are water-dwelling, segmented animals,

- in extreme conditions, they dehydrate, reducing to 3% of their normal mass,

- they can go without food or water for ~30 years, rehydrate, and then reproduce,

- and can survive in temperatures ranging from 1 K (just above absolute zero) to 420 K (well above boiling).

But they are not extremophiles. In other words, they can go into some sort of suspended animation “survival mode” in these harsh conditions until more favorable ones arise, but they do not thrive under these conditions. But in Star Trek: Discovery, the giant version is hairy, with a non-segmented body, is non-aquatic, and can navigate through and thrive in space just fine. It’s science fantasy, not science fiction.

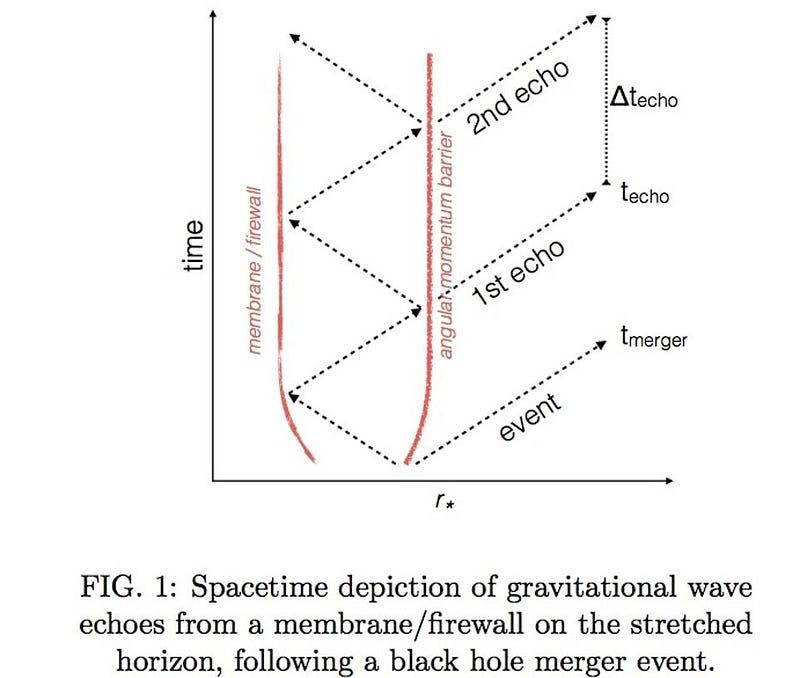

The “Hawking radiation firewall” is some strong evidence that they don’t actually have a science consultant to help with the writing of the show. By combining two unrelated ideas about black holes, Hawking radiation and black hole firewalls, they create a nonsense term and then invent some mumbo-jumbo about how running into it is bad. Yes, running into a black hole would be bad, but there’s no such thing as a Hawking radiation firewall, and it’s unbelievable that they wouldn’t have a map of where black holes are given the other technology in Star Trek some 200+ years in the future.

Hawking radiation is the radiation emitted by the very slow decay of black holes due to quantum effects just outside the event horizon. There will not be a black hole that emits enough Hawking radiation to ionize a single atom in the Universe for another 10⁶⁰ years or so, and even when they do, it will be because the black hole is on the verge of evaporating entirely. A firewall is the idea that either at or just outside a black hole’s event horizon, high-energy radiation surrounds it, frying whatever falls in before sucking it into a singularity. Combining them into “Hawking radiation firewall” and having that murder the crew while leaving the ship intact is what someone whose science education comes from memes on the internet might write into a television show.

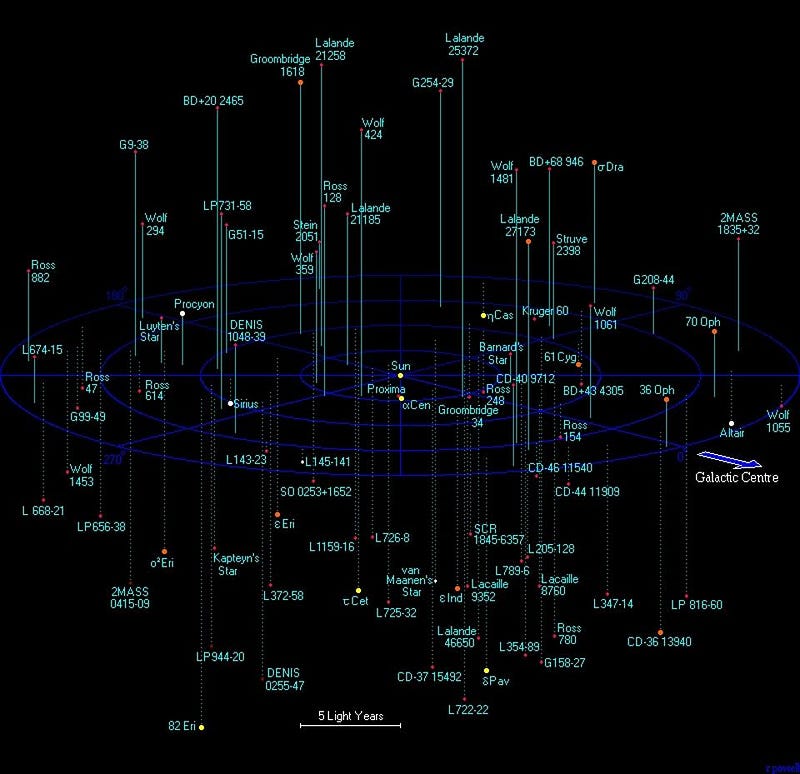

Meanwhile, how do you not have a map of the galaxy yet? Humanity is poised to directly image our first black hole, and its event horizon, thanks to a network of radio telescopes all across Earth. That’s what determines your resolution: how far apart your telescopes are. Are you telling me that hundreds of years in the future, where we have starships that are light-years apart, we still haven’t taken a galactic census of black holes? That they still surprise us?

No matter; apparently we’re not even mapping out stars and planets and putting that into a database, because we need mysterious, mystical, mushroom-spore-communicating aliens to talk to us. And apparently, we don’t have the computational resources that we can expect to have in about 20–50 years more than 200 years from now. We’re making incredible developments in the field of quantum computing, and yet we can’t even calculate a trajectory successfully because we don’t understand how to choose an outcome from a probability distribution. You might say, “of course we don’t, that’s impossible,” and under the laws of quantum mechanics, you’d be right. But aliens like Ripper can somehow do this, while the 23rd century’s best computers can’t? I’m not impressed.

Right and wrong: At last, we see a tiny glimmer of morality from Star Trek: Discovery, as Burnham realizes that imprisoning and exploiting other species, like whatever “Ripper” is, for your own gain is suspect. But lying to your crew, sneaking into places you don’t belong, and taking things that don’t belong to you, as well as meddling in the experiments of others, is second-nature to you. Sure, you want to win the war and save lives, but at what cost? It’s only in comparison to a joke character like Landry that Burnham’s actions display some sort of morality, where Landry’s treatment of the captured Ripper is about as justifiable as the way a cat treats a captured mouse.

But the alleged saving of the Federation colony is the most irksome development in the show. When Lorca speaks with the Federation, they tell him how many Klingon vessels are within range of the colony, how it’s up to Discovery to save them, and that no other help is coming. Discovery gets there with seconds to spare thanks to the jumping technology, sets a trap for all the Klingon ships, then blows them up as it jumps away. And then… just leaves the colony? To die? To fall prey to the next Klingon ship to come by? They don’t return; they don’t evacuate anyone; they don’t provide relief of any type. I guess it’s the perfect analogy for Hurricane Maria and Puerto Rico, but I seriously doubt that was the show’s intent.

Meanwhile, I left the entire Klingon plotline out of the recap, because it does nothing but eat up screen time with actors so heavily-laden in prosthetics that their faces don’t move. The three relevant Klingons are Voq, the “torchbearer” for the legacy of T’Kuvma; L’Rell, T’Kuvma’s former second-in-command, and Kol, the Klingon who was opposed to T’Kuvma’s fanatical rise. We learn that T’Kuvma’s cloaking device is the only one of its kind in the Klingon Empire, and the other houses want it. Voq and L’Rell argue over the ideological purity of cannibalizing the USS Shenzou for its components. After six months of starving and floating, stranded, in space, they finally take the dilithium. But it’s too late; Kol takes T’Kuvma’s old ship (and technology) over from Voq, convincing the entire starving crew to join him with the delivery of food. L’Rell fakes loyalty to Kol to save Voq’s life, leaving him stranded aboard the Shenzou. As Kol rises to power, L’Rell goes to Voq to tell him to sacrifice everything and rise to power. It’s like a choose-your-own dictatorship over there: do you prefer hegemony with or without theocracy?

Conclusion: The hallmarks of Star Trek have always been placing characters into challenging situations where they have to face moral dilemmas analogous to the ones we’re facing in society, today, in a science-fiction setting. The crew has to find common ground with someone or something that is very different from themselves, and seek a mutual understanding to increase knowledge and achieve peace. Obviously, set against the Klingon/Federation war, this is a different series, but I have an increasingly sinking feeling about this.

Discovery is the NCC-1031, and I want you to think about that number. Why? Because Starfleet has “Section 31,” which is their black-ops division that’s tacitly permitted to take extreme measures under threatening conditions. We have “black alerts” on the Discovery; we have secret research projects and secret weapons. And we have a Captain committed to winning by any means necessary. I have a feeling that the Federation is developing a doomsday weapon, aboard discovery, that they plan on unleashing on the Klingon Empire. Will this change the Klingons’ appearances back to the Klingons we know? Will it blow up the moon of their home world, Qo’nos, as occurred in the alternate timeline from Star Trek: Into Darkness?

I can’t help but wonder how different this show would be, and how differently the characters would have been portrayed, if Bryan Fuller has been allowed to realize his dream. What we have instead is superficial science and unexamined amorality: the antithesis of what Star Trek has always been about. Perhaps another visit from Sarek is in order; this episode has left me less hopeful than ever that Discovery will be the Star Trek series our world needs now more than ever.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.