The Suspect Science Of Star Trek: Discovery, ‘Context Is For Kings,’ Season 1, Episode 3

It isn’t just the morality that’s dubious in the newest iteration of Star Trek.

“If I die trying but I’m inadequate to the task to make a course change in the evolution of this planet…okay I tried. The fact is I tried. How many people are not trying. If you knew that every breath you took could save hundreds of lives into the future had you walked down this path of knowledge, would you run down this path of knowledge as fast as you could.” –Paul Stamets

All’s fair in love and war, but does that make it right? After watching the third episode of Star Trek: Discovery, Context is for Kings, which sees its main character, mutineer Michael Burnham, brought on board the USS Discovery, it sure doesn’t seem so. In shades of the post-WWII Operation Paperclip, where thousands of Nazi scientists were brought to the United States for their expertise in the field of Rocket Science, Burnham is brought on board the USS Discovery, a “research” ship unlike any other we’ve ever seen in the Federation, and we get our first glimpse of exactly what it is they’re researching. While the biological and physical stories presented makes for a very convenient and intriguing plot device, the science, and the ethics, simply fails to add up.

Recap: The show opens with disgraced officer Michael Burnham on a prison transport ship. Unlike the other prisoners, she’s silent, stoic, and displays no outward reaction when species GH54, some micro-bugs that feed on the ship’s energy, threaten to disable and destabilize life support on the transport ship. The pilot goes outside to combat the bugs, only to be thrown into the abyss of space. As the remaining passengers descend into panic, we get out first view of the USS Discovery, as it pulls in the prison ship with a powerful tractor beam.

Once aboard the Discovery, and a victorious scuffle in the mess hall, it quickly becomes clear that Burnham isn’t destined for life in prison at all, but that there’s a tremendous interest in her knowledge and skills. She meets the (literally) starry-eyed Captain, Gabriel Lorca, an eccentric not-what-he-seems type who has an obsession with his family’s old business: making fortune cookies. (We only ever see the cookies; never the fortunes.) “Maybe the Universe hates waste,” Lorca explains, as he explains that his mission is to win the war and send everyone home, and he’s going to use all the resources available to him to do that. That includes Burnham, whether she likes it or not. Burnham meets her special-needs odd-couple-esque roommate, Cadet Sylvia Tilly, who engages in mindless small-talk but won’t tell Burnham what’s really going on aboard Discovery when the “Black Alert” is called.

Burnham, now back in uniform, re-meets Saru, who’s now Discovery’s first officer. He treats Burnham kindly but distantly, expressing his disappointment and demonstrating that he’s yet to forgive Burnham, but that he’s willing to give her another chance. She’s assigned to work under Lieutenant Paul Stamets, who seems to be based precisely (and almost literally) on the mycology-obsessed scientist and advocate, Paul Stamets. (Stamets is perhaps most widely-known for his TED talk.) Stamets assigns Burnham to work on reconciling some code fragments, and the logically-minded Burnham notices equations related to both quantum astrophysics and biochemistry, and has some questions about her work, having found a mistake in the code. Stamets, annoyed at Burnham’s presence and curiosity, dismisses her.

Burnham, uses the sleeping Tilly’s drool to gain access to Stamets’ lab (do they not have two-factor authentication in the future?), discovering the spore-emitting hydroponic forest in his lab. Meanwhile, Lorca receives a transmission regarding Discovery’s sister ship, the USS Glenn, where Stamets’ closest collaborator is found dead, and sends an away team on a shuttle, Burnham included. The probing Burnham asks again whether this is physics or biology, and Stamets loses his patience (but starts talking), revealing that he sees:

- there is no difference at the quantum level between biology and physics,

- that spores are the seeds of panspermia, the spreader of life across the Universe,

- and that he’s an astro-mycologist because of his awe at this miracle.

He also reveals that his best friend is dead because of their mutual research, and he doesn’t trust the war-mongering Lorca. They arrive on board, find a Klingon-and-human-eating monster, as well as Stamets’ friend’s corpse, and all barely escape with their lives.

Back on Discovery, Saru praises Burnham, while Lorca invites Burnham, then appeals to her sense of curiosity, in an attempt to convince her to serve on board the Discovery. It becomes clear that Discovery is more of a black ops vessel, engaged in sketchy-at-best R&D to uncover some big scientific secrets, under Lorca’s command. At the very least, a biologically-powered starship propellant is under development, tenuously linking the mycology network of spores with the cosmic network of matter and energy. He sends a skeptical Burnham on a split-second journey to a variety of worlds, convincing her of the new technology’s potential, and its use in combating the Klingons, and in ending the war that she helped start. She ends by quoting Alice in Wonderland, with the lesson being that the world doesn’t always adhere to logic:

Sometimes down is up,

Sometimes up is down,

Sometimes when you’re lost, you’re found.

At the show’s closing, we learn, as the USS Glenn is destroyed by Discovery, that the violent creature that Stamets and Burnham barely escaped from is being held by Lorca, potentially for use as the ultimate biological weapon.

Science: Star Trek has always pushed the envelope when it comes to speculative ideas about physics and astronomy. Parallel Universes not only exist, but can overlap and intersect as the fabric of spacetime can be broken down. Dyson spheres are real, enclosing entire stars and gathering 100% of their outputted energy. And now Star Trek: Discovery pushes the envelope in a new way: with panspermia and the biology/astronomy connection.

On the surface, it seems like an intriguing argument. Life as we know it has adapted to fill potentially every niche we can imagine, so why not extend that into space? Why couldn’t organisms adapt to feed on pure energy, even if it’s completely parasitic, in order to survive on a traveling starship’s power? That part is eminently reasonable, even if we’ve never found or engineered a candidate for that. At the very least, that idea is plausible.

It’s when we get to Stamets’ explanations, however, that we see how creative Discovery’s writers get with what’s scientifically feasible. There’s a big difference between physics and biology, and simply the fact that both obey the quantum laws that govern all particles isn’t enough to sweep that under the rug. From a single cell to a human being, the difference between a living (biologically active) and non-living (biologically inactive) system, like the difference between a human and a cadaver, isn’t about the quantum state of particles. It’s about energy transport. If you stopped the flow of electrical energy in your brain, you’d still be the same, physically; biologically, however, you’d be very, very different. You’d have ceased to exist.

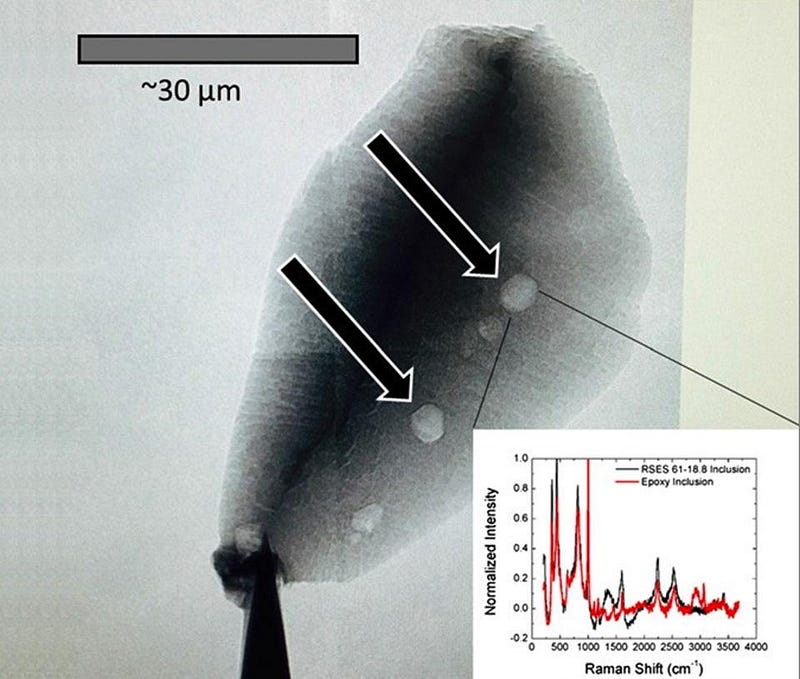

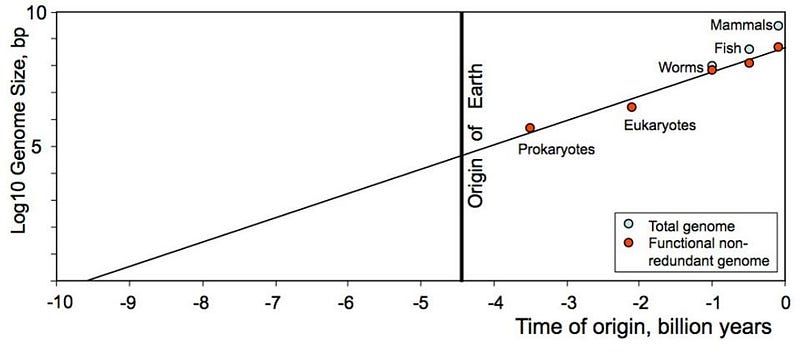

Panspermia is an intriguing and compelling hypothesis. The farther back we go in the geological record, the earlier and earlier we find circumstantial evidence for life on Earth from its inception, currently hitting the four billion year-old mark. If we look at the complexity of life on Earth over time, the extrapolation leads us to the possibility (or even probability) that life began elsewhere at earlier times, and its seeds came to Earth in the early stages. And even if we look at asteroids that have fallen to Earth or to interstellar space, we find the building-blocks of life in the most inhospitable and inorganic of places.

But it is not spores or fungi that seeded life throughout the Universe. When we look at the evolution of life on Earth, fungi, plants, and animals are all latecomers; bacteria and other simplistic, prokaryotic organisms are the seeds from which all the other kingdoms arose. Fungi might be the closest animal relatives among kingdoms in biology, but they are not the seeds of life in the Universe.

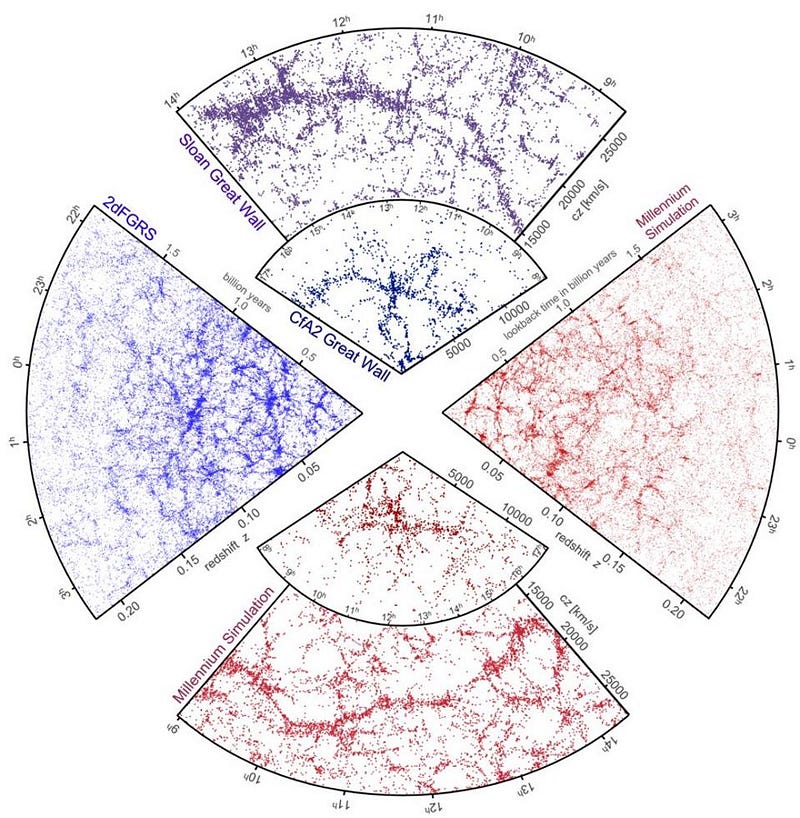

And despite the fact that fungi form complex underground networks, providing the seeds for the fertile humus that plants thrive in, that web is in no way connected to the cosmic web of matter and dark matter that binds the large-scale structure of the Universe together.

Even if they did obey the same mathematical equations (they don’t), there’s not a physical connection there. These are independent systems, and even in a Universe where the Vulcan mind-meld is routine, instantaneous consciousness transferral across hundreds or thousands of light years is not even science fiction; it’s wish fulfillment. The idea of biofuels and bio-propulsion is nothing new, nor are the genetically-altered ravaging monsters we see at the end. But actual mental journeys to physical places? Unless you can recreate the electrical patterns that compose someone’s mind a great distance away, andquantum entangle them across that cosmic distance (which can only happen at-or-below the speed of light, mind you), it’s never going to be physically feasible.

Right and wrong: Unlike other iterations of Star Trek, where humans were placed into unknown, perilous situations and forced to choose between morally ambiguous and difficult options, Star Trek: Discovery doesn’t weigh in on the answer. Lies, incomplete information, misdirection, even the death of many as a consequence of a questionable action isn’t enough to cause even a re-evaluation of the current plan. What’s completely glossed over, as in, no one discusses it, is that a lone Klingon is encountered on the USS Glenn, and the Klingon attempts to warn the Federation crewmembers about the monster, before being mauled to death by said monster.

I was worried, after the first two episodes, that Star Trek: Discovery would be more like War Trek than Star Trek. After “Context Is For Kings,” I’m convinced that this is going to be more about the secret weapons being developed (and potentially used) than exploring the ethical questions surrounding them. We’ve noticed that the Klingons we’ve seen so far in this series look very, very different than the Klingons we’re used to, and they’re treated as sub-human at every turn.

Could the biological weapons the Federation is developing have something to do with the appearance of the Klingons? Will the Federation do something to the Klingons that forever change who and what a Klingon is? Like all of the ethical questions thus far raised by Discovery, these, too, will likely go unanswered and unexplored by the show. There is no moral, right-and-wrong voice in this show as of yet, and I’m not certain it’s going to get one.

Conclusion: We finally know what the Discovery is: a testbed for the equivalent of the 23rd century’s Manhattan Project. Can they make a weapon so powerful and irresistible that it will end the Federation-Klingon war? Will there be side-effects or fallout, and will that even factor into the decision-making process about whether to drop this sort of “bomb” on the Klingons? Honestly, the closest analogy we have in Star Trek canon is when a young Ensign Riker defended Captain Pressman aboard the USS Pegasus, where they were engaging in forbidden, treaty-violating research into Federation cloaking technology. This dark side of the Federation is rarely exposed; in Star Trek: Discovery, it’s a way of life.

Although it still doesn’t feel like a Star Trek series, it does feel like a high-quality space adventure. It’s beautiful, it makes you think, and if I had never seen the previous Star Trek series before, I would be quite pleased about this show. While many across the internet are judging it through the lens of what they expect and hope Star Trek would be, and I am definitely sympathetic to what such a series could do for the world, on its own merits, it’s an interesting story. And now that we’ve met the crew of the Discovery, I’m curious to see where we boldly go from here.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.