The Terrifying Physics Of How Wildfires Spread So Fast

Just a few simple, common conditions can create the perfect storm. 80% of the time, humans are the trigger.

“I’d rather fight 100 structure fires than a wildfire. With a structure fire you know where your flames are, but in the woods it can move anywhere; it can come right up behind you.” –Tom Watson

At about 3:30 PM on a Saturday afternoon, Kevin Marnell was hiking along Eagle Creek in the scenic Columbia Gorge, along the border between Oregon and Washington. The National Scenic Area has been protected for over 30 years and contains the only navigable river to run through the Cascade Mountain range to the Pacific Ocean. Rainforests and grasslands have created a thriving ecosystem along both the Oregon and Washington sides, with humans living there for some 13,000 years. On the afternoon of September 2nd, Marnell heard loud banging sounds, like gunfire. He soon realized it was worse than gunfire, as thick smoke began rising nearby.

Two (at least) teenage boys were tossing fireworks off a cliff and into the gorge, and one didn’t make it, going off in the forest. Just hours later, 153 hikers in the Eagle Creek area were stranded, needing to be rescued and evacuated. Within 24 hours, more than 3,000 acres were engulfed in flames. The nearby town of Cascade Locks was evacuated over Labor Day weekend, followed by five other towns. By that Tuesday morning, a thick haze blanketed most of western Oregon and Washington states, reducing the air quality to the most dangerous levels. Throughout that Tuesday, ash fell from the skies in Portland, accumulating more than an inch in places, as the fire swelled to over 10,000 acres in area. Embers crossed the Columbia River, spreading the fire into Washington State as well.

The fire continues to race westward at an alarming pace, at one point having traveled 13 miles in a span of just 16 hours. Monday and Tuesday evening, 600,000 young hatchery fish were released up to six months early, as it was the only way to give the fish a chance at life in the face of the approaching wildfires. Over 4,500 people had been evacuated from their homes as of that Wednesday morning, and the fire continued to spread, having reached 30,000 acres as of midday on Wednesday. Six days ago, officials were considering whether to order a mandatory evacuation for parts or, potentially, the entirety of Portland, OR. It’s never been more important to understand why and how wildfires are so dangerous, and how they can spread so quickly. Four out of every five wildfires are caused by human activity, and this one may prove to be among the most catastrophic in recent history.

Every summer, when it’s been dry enough for long enough, all the counties west of the Cascade mountain range throughout Washington and Oregon place a burn ban in effect. Summer is wildfire season out here, as the long, wet winters and springs we experience lead to a tremendous amount of tree growth and undergrowth; this past year was particularly spectacular for that. While much of the west coast saw long-standing drought conditions alleviated, we also received record-setting rainfalls in places, both in terms of total accumulation and in the number of consecutive days with precipitation.

All of this served to create a huge amount of potential “fuel” for wildfire season. Coupled with the warm, dry summers that the pacific northwest experiences — and it’s been uncommonly warm this year — that fuel becomes easily combustible. Oxygen is never a problem in this region of the country, and the Columbia Gorge, in particular, is notorious for breezes and continuously-moving air. That means, during the dry season, where you have lots of highly flammable plant matter to serve as fuel, oxygen to keep it burning, and high temperatures and winds to help spread the fire, all you need is something to ignite it. In 80% of situations, that’s a negligent or malicious human.

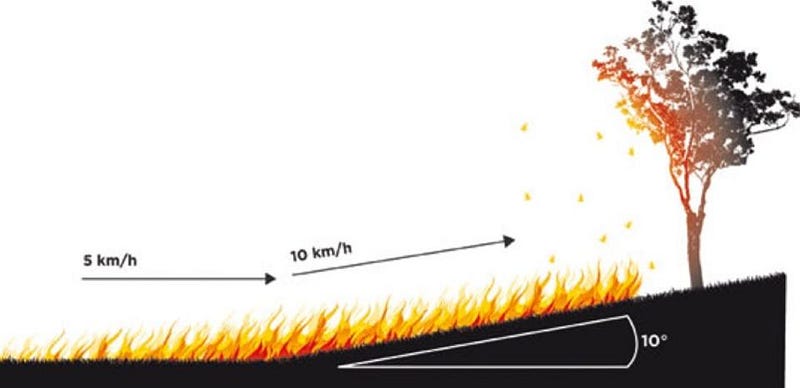

Fires can travel quickly: up to 6 miles-per-hour in forests and up to 14 miles-per-hour in grasslands. If you have an upward-slope to your terrain, the flames can travel even faster; an extra 10 degrees of slope will double the speed of your fire. It’s the reason why, if the fire started near the bottom of the Columbia Gorge, it’s only a brief amount of time before it spreads up and engulfs the entire valley.

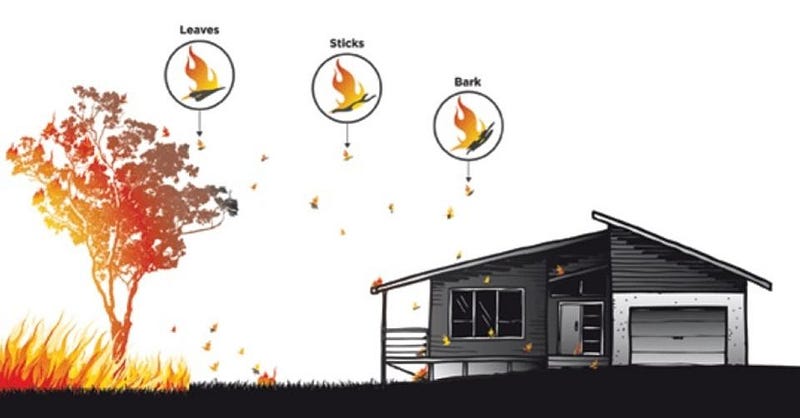

The fires can also spread to homes, jump cleared areas, or even cross natural firebreaks like rivers, owing to what’s known as an “ember attack.” When high-standing plant matter (like trees) catch fire, burning twigs, leaves, and pieces of debris can be carried large distances by the wind, still aflame after traveling tens or even hundreds of feet through the air. Any small, dry, easily flammable thing that it contacts can easily catch fire, from a leaf on another tree across a body of water to the dried pine needles in a house’s rain gutters. If the fire gets too close to a major city, it becomes much more an issue of rescuing and evacuating people than it does about saving homes and preventing property damage. Just a few months ago, 62 people were killed owing to a wildfire in Portugal.

While it’s true that 20% of fires have natural causes — mostly lightning strikes — the remainder, and hence the vast majority, are caused by human activity. There are burn bans all throughout Washington and Oregon that have been in place for two months, but all it takes is one spark to begin that fiery combustion reaction, and the dry, flammable flora can turn it into a catastrophe. While the press may be calling the firestarters “idiot teenagers,” which they may well be, they’re also arsonists, having knowingly started one of the worst fires in a protected (and populated) area that Oregon has seen in decades. As Alex Berezow wrote for the American Council on Science and Health:

All of this was entirely preventable. And all of this was entirely foreseeable; even teenagers understand the consequences of their actions. But they just didn’t care. They didn’t care that a forest fire could not only destroy a true natural treasure, but that it could threaten the lives of thousands of people and cause millions of dollars in damage.

The good news, though, is twofold:

- The fire is likely to slow down its spreading, as temperatures are dropping and winds are blowing only slowly. Rain is even forecast for parts of the valley later this week.

- The Columbia Gorge, being a temperate rainforest ecosystem, will recover quickly. Shrubs and bushes will return within 12 months; young Douglas Firs will tower over humans in a decade. Within about 30 years, there will be scant evidence to hikers, passersby, wildlife, and even forest rangers that there was ever a fire here.

Fires like this can be prevented, but it’s up to all of us to be responsible. One evil or negligent action, even a small one, can grow to an uncontrolled catastrophe: destroying thousands of acres of land, displacing thousands of people, causing millions of dollars worth of damage, and may even threaten to burn a major city before it’s all over. The iconic Smoky the Bear may say “only you can prevent forest fires,” but the truth is that everyone has to be on board. It’s up to all of us. It’s not merely something we “can” do, but rather something we “must” do.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.