These Are The Dangers Of Visiting Even One Friend During The COVID-19 Pandemic

Visiting even one friend can undo all the good work that social distancing has accomplished.

Over the past few months, people all over the world have come to realize just how serious and deadly the current COVID-19 pandemic actually is. The number of confirmed global cases now exceeds 2.7 million, with a significant percentage of those leading to serious (or worse) complications. At the time this article was written, the number of COVID-19-related fatalities is approaching 200,000, with more than a quarter of those occurring in the United States alone.

And yet, there’s cause for both hope and concern. Social distancing appears to be working: the infection rate appears to be falling as we flatten the curve. The number of new infections and the number of new deaths per day appear to be reaching their peak. But now is the most critical time to keep social contact low. While many clamor to “reopen America,” a team of network epidemiologists are actively warning against close physical contact with even one person outside your household. Here’s the science behind why.

Whenever you have an infected and contagious population, the ideal situation would be to isolate everyone who’s infected from everyone who’s not infected. If we could successfully do that, then everyone who’s currently uninfected would remain so, and everyone who’s infected would be unable to transmit the disease to others. In other words, if we successfully quarantined every person, individually, this disease would be unable to spread.

Of course, that’s not a realistic scenario. For one, people live in households, and so each person cannot successfully isolate from the people they live with. For another, people require essential goods and services: food, medicine, healthcare, police and fire services, etc. For this and many other reasons, it’s impossible to keep everyone completely isolated from everyone else. If we could, isolation practices could successfully stop the spread of SARS-CoV-2: the virus that causes COVID-19.

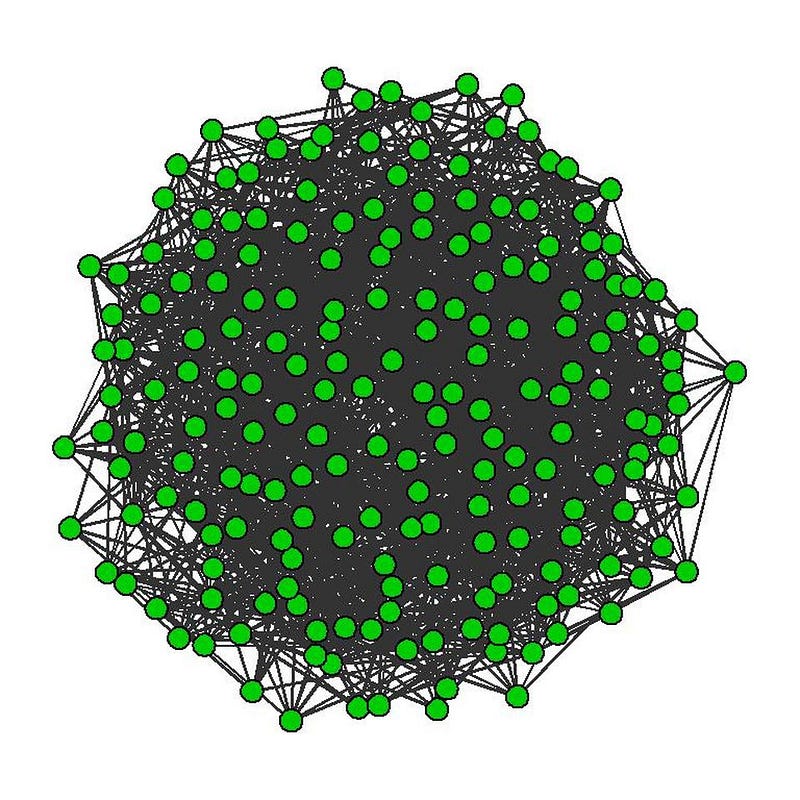

On the other hand, the worst possible outcome would arise if there were absolutely no efforts made to avoid physical contact with others. If everyone came into close physical contact with one another, and some non-negligible percentage of the population were infected, then practically everyone would become exposed to the virus in very short order.

This would lead to the worst possible situation imaginable from a public health perspective: a situation where not only will everyone get infected, but most of the infections will all happen at the same time. The whole point of the push to “flatten the curve” is to spread out the infections over time, particularly the serious infections that require professional medical interventions. Largely due to the social (i.e., physical) distancing measures that people have been employing, the worst possible outcome has been avoided so far.

But everything is now contingent on what we do next. If we continue to physically distance ourselves as we’ve been doing, we can expect that the number of new infections will gradually decline over time, followed by a decline in the death rate. If we put an end to the requirement for physical distancing, some percentage of the population will voluntarily decide to continue with it, but some percentage will not.

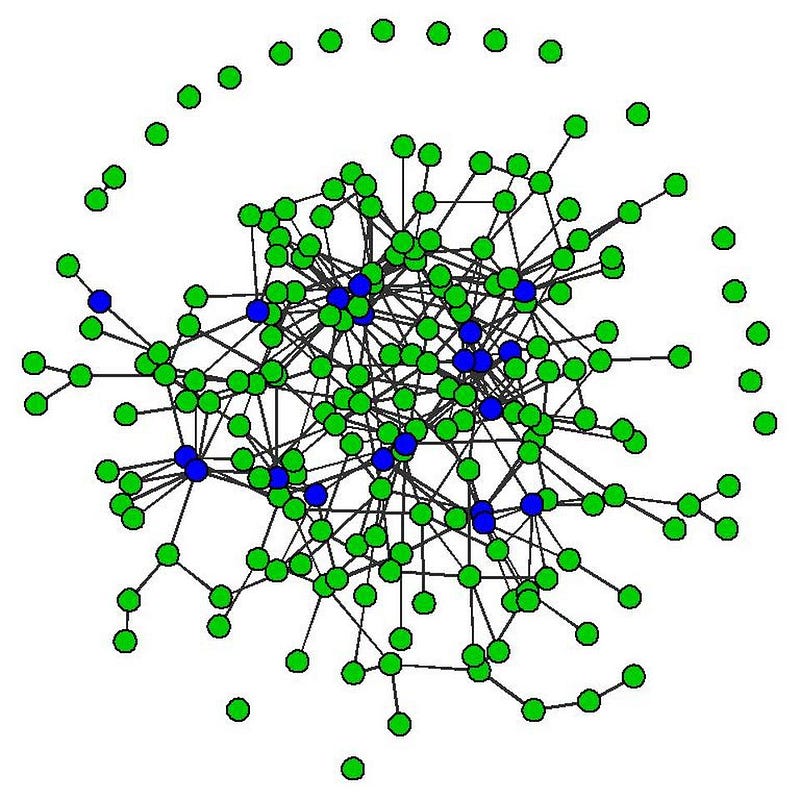

Among those who don’t and those who come into close contact with those who don’t, the infection rate will go right back to growing exponentially, just as it did in the early (pre-social distancing) stages of this pandemic. Everything is contingent on our behavior, and that’s where the science of network epidemiology comes in. Based on factors associated with the disease and how the susceptible population behaves, scientists can come up with the expected consequences under a variety of scenarios.

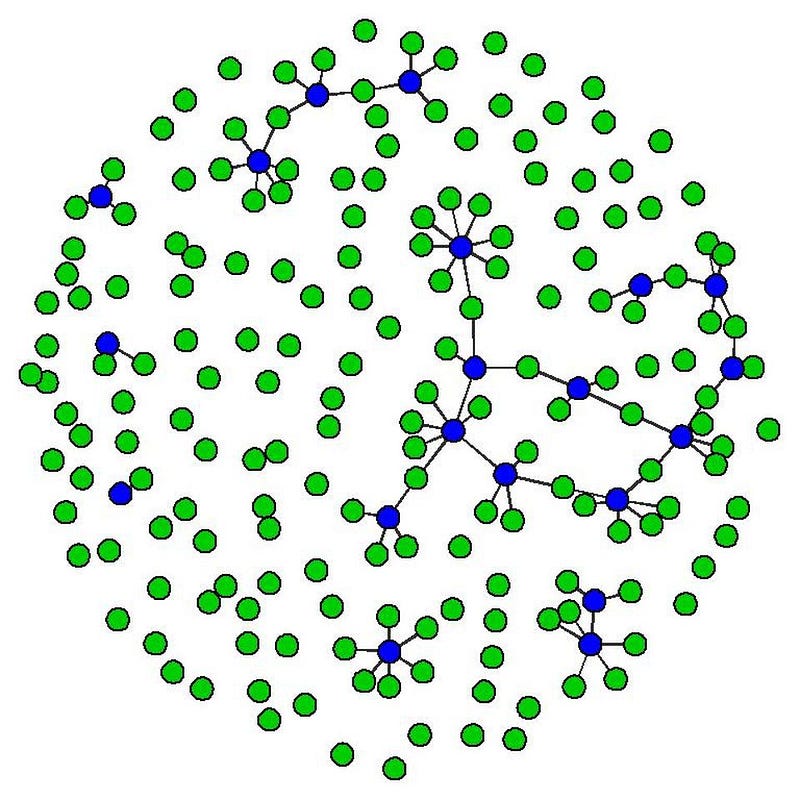

Earlier this month, a team of network epidemiologists from the University of Washington put out a study designed to answer a deceptively simple question: what are the consequences if I visit, without enforcing physical distancing, just one person outside of my household?

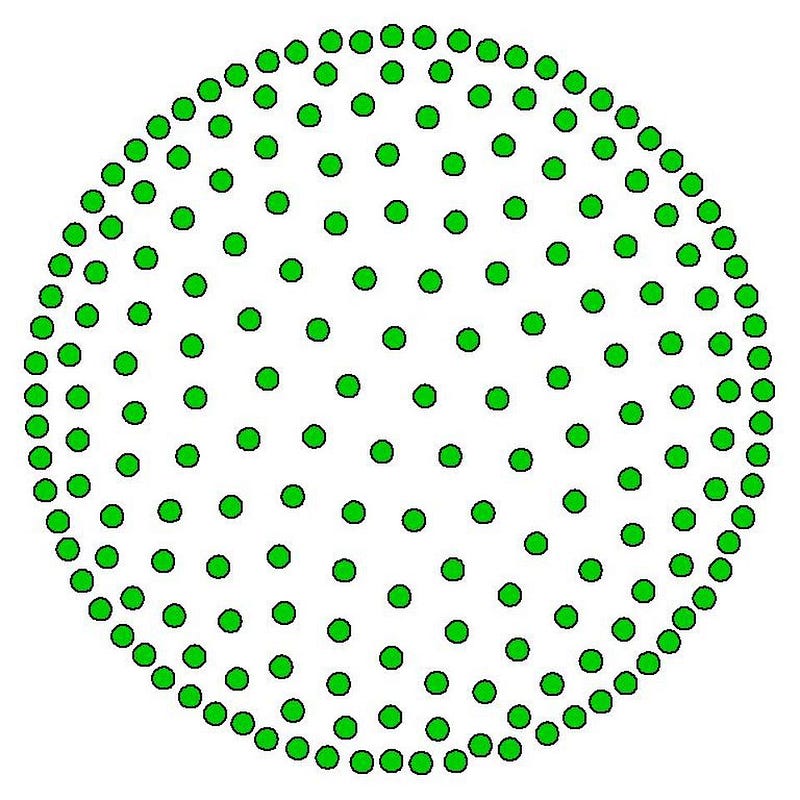

To answer this question, they started with the best realistic scenario: simulating what would happen if only the essential points-of-contact between people occurred. This is unavoidable at some level. Health care workers have to interact with their patients. Workers in the food service industry have to come into contact with their customers. The power has to stay on. Clogged chimneys need to be swept. Internet access is a vital service. Person-to-person contact cannot be avoided entirely.

Even when all the optimal precautions are followed, there’s still a non-negligible risk of disease transmission, as evidenced by the enormous number of health care workers who have fallen ill (and many who have died) from COVID-19.

That’s the realistic best-case scenario: where only essential points-of-contact occur. Yet even in this scenario, the virus still has some room to move around. Doctors, nurses, and EMTs interact with patients and one another; food growers, harvesters, and food transporters all need to interact; water and electricity services need to continue; etc.

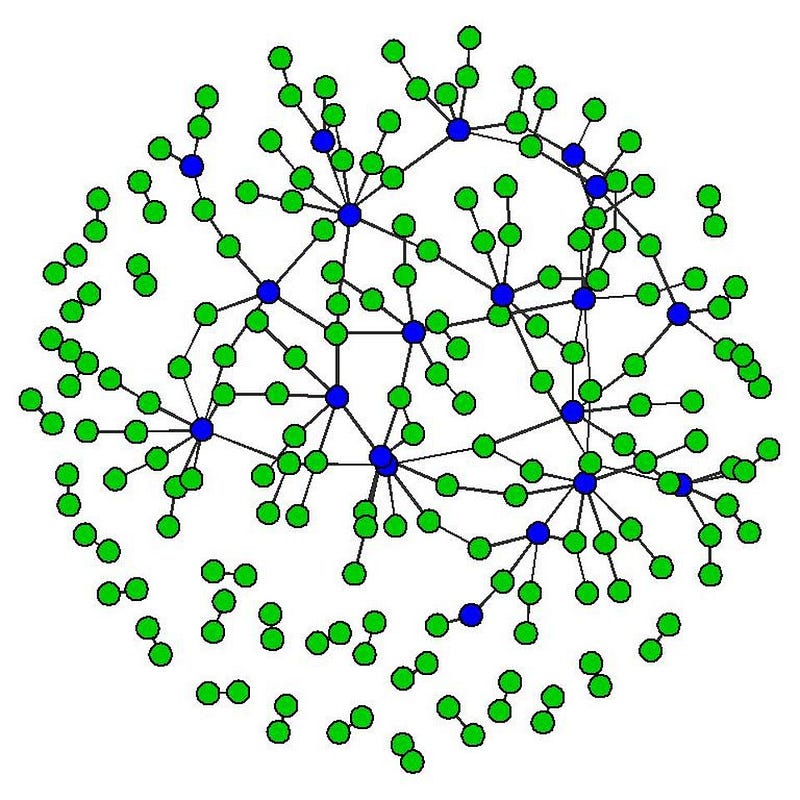

It’s not just 1-to-1 transmissions, but even with only essential workers, networks of potential disease transmission paths emerge, with the largest one affecting up to 26.5% of households. Even in this best-case scenario, the researchers note that many infections and deaths will be unavoidable.

Let us be very clear here: some people are going to get infected, and some people are going to die, because of these connections. It’s that simple.

But these connections are so essential that we as a society are willing to make that trade-off. Without them, many more people would die of other basic things besides COVID-19: starvation, freezing, crime, other diseases.

With all of these essential connections still occurring, it’s hard to see why adding one more in, especially if it’s limited to one-per-person or even one-per-household, would be so dire. As the researchers themselves testify, they’ve commonly heard the same question from a wide variety of populations, “is there really so much harm in meeting up with just one friend?”

Although it might seem low-risk, particularly if there are no elderly or immunocompromised people living in either household, these connections matter more than you might intuit. Visiting even one person without enforcing strict distancing measures, including:

- allowing children to play together,

- having a teacher or tutor come over,

- or close physical contact between two adults who live in different households,

can significantly increase the connectedness between many households that would otherwise be completely isolated.

If each person in a household (with 2.6 people in the average American household) visits only one other person outside of their household, many things worsen dramatically. The three biggest are as follows:

- The largest networked cluster grows by 240% over the essential-only scenario.

- Over 90% of households are now connected, as compared to just 26.5% in the essential-only scenario.

- The average household is now connected to 36.8 other households within 3 degrees of separation, compared to just 4.2 for the essential-only scenario.

Even in a scenario when only one person-per-household visits with only one person from another household, the respective increases are significant. The largest networked cluster grows by 168% over the essential-only scenario; 71% of households are now connected; the average household connects to 12.1 other households within 3 degrees of separation. As the authors summarize,

In short, we see many many more opportunities to acquire the virus from folks who are both near and far from you in the social network. And equally more opportunities for you to transmit it on to other folks both near and far.

All just so people can hang out with one friend!

The key point that we all have to remember is this: the health and safety of everyone — ourselves and our families included — is contingent on what we do next as a society. The best actions we can take, if we’re interested in saving lives and reducing the spread of this infection, are to postpone every single additional connection possible with individuals outside of our own households.

There are always going to be connections that are absolutely essential: connections that, were they to be severed, would pose an even greater threat to our health and safety than the risks that COVID-19 poses. Every connection is also a possible disease vector, and that means every non-essential connection that we make increases the risk of more infections, more deaths, and a longer waiting period before it’s safe to reopen society. The consequences of visiting even one friend now can be dire. Waiting until it’s safe is worth it for us all.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.