This Is Why Three Of The Lightest Elements Are So Cosmically Rare

Helium and carbon are made copiously in the interiors of stars. But the in-between elements? They’re rarities everywhere.

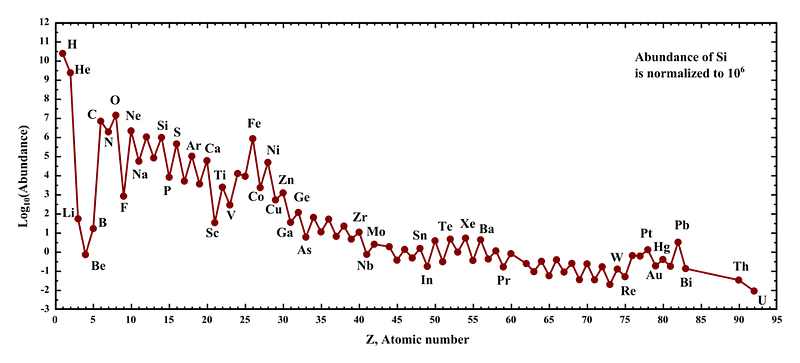

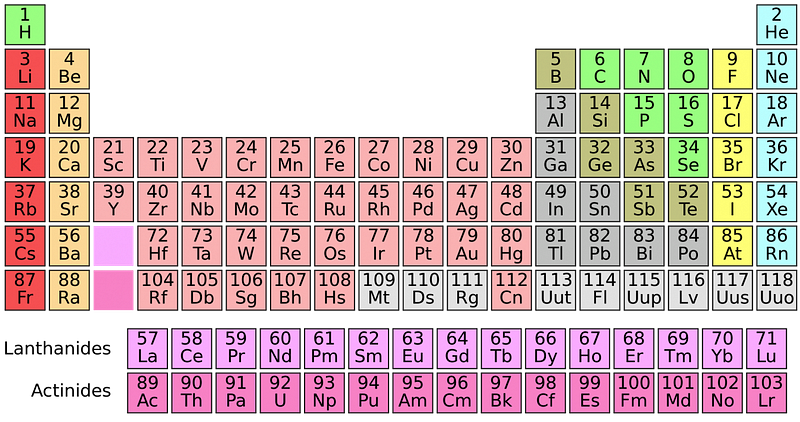

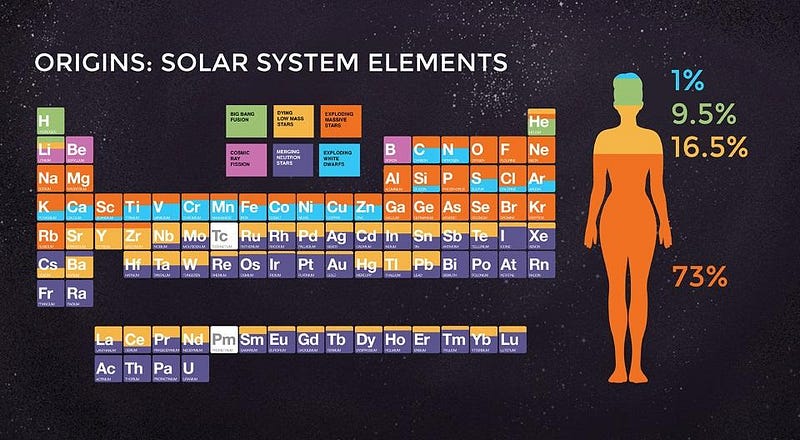

If you were to take every element in the periodic table and order them by how abundant they are in the Universe, you’d find something a little bit surprising. The most common element is hydrogen, composing nearly three-quarters of the Universe by mass. At about one-quarter is helium, produced mostly in the early stages of the hot Big Bang but also produced by the nuclear fusion occurring in most stars, including our Sun.

Beyond that is oxygen at #3, carbon at #4, followed closely by neon, nitrogen, iron, magnesium and silicon, all of which are produced in the interiors of hot-burning, massive, and giant stars. In general, heavier elements are rare and light elements are abundant, but there are three big exceptions: lithium, beryllium, and boron. Yet these three elements are the 3rd, 4th, and 5th lightest of all. Here’s the cosmic story of why they’re so rare.

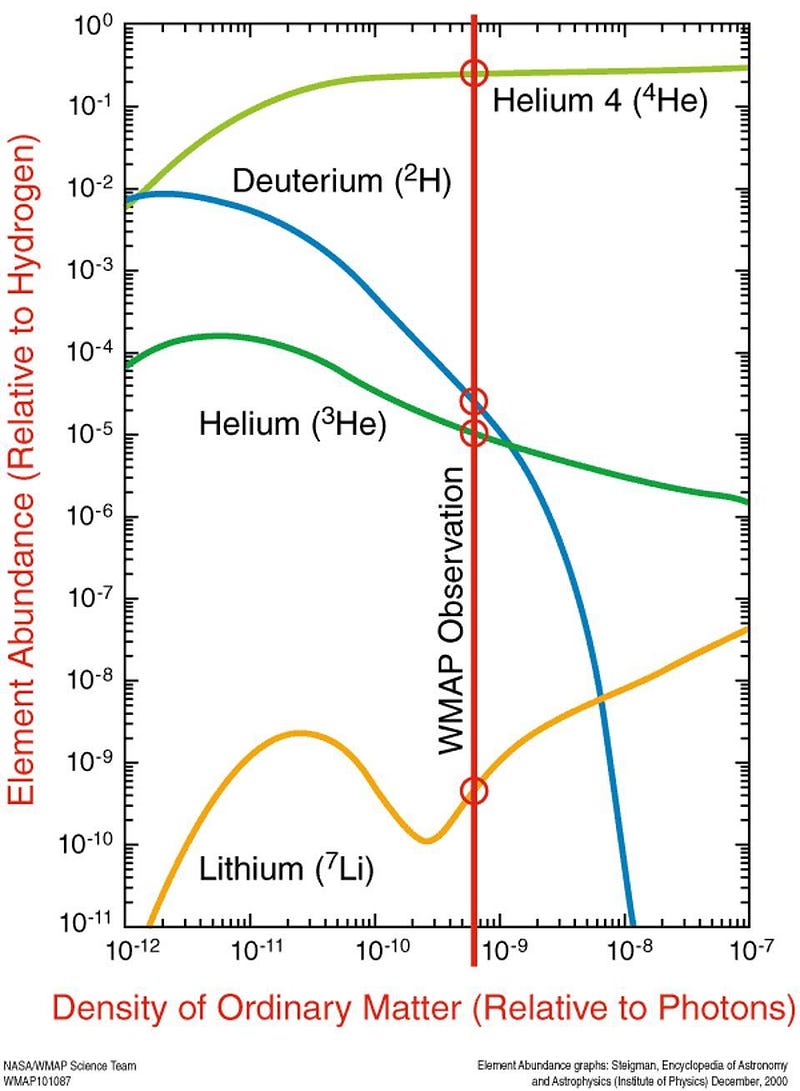

In the immediate aftermath of the hot Big Bang, the first atomic nuclei formed from an ultra-energetic sea of quarks, leptons, photons, gluons, and antiparticles. As the Universe cooled, the antiparticles annihilated away, the photons ceased being energetic enough to blast bound nuclei apart, and so the early Universe’s protons and neutrons began to fuse together. If we could create the heavy elements found on planet Earth, the Universe could have been ready for life from the time the first stars were born.

Unfortunately for our dreams of the Universe being born with the ingredients necessary for life, photons remain too energetic to form even the simplest heavy nucleus — deuterium, with one proton and one neutron bound together — until more than three minutes have passed since the Big Bang. By the time nuclear reactions can proceed, the Universe is only one-billionth as dense as the center of the Sun.

This is still a pretty good deal, as it gives us a Universe made of about 75% hydrogen, 25% helium-4, about 0.01% deuterium and helium-3 each, and approximately 0.0000001% lithium. That tiny amount of lithium is what existed before any stars in the Universe formed, and that’s a really, really good thing for us, because lithium is a pretty important element for many applications, technologies, and even biological functions here on Earth, including in humans.

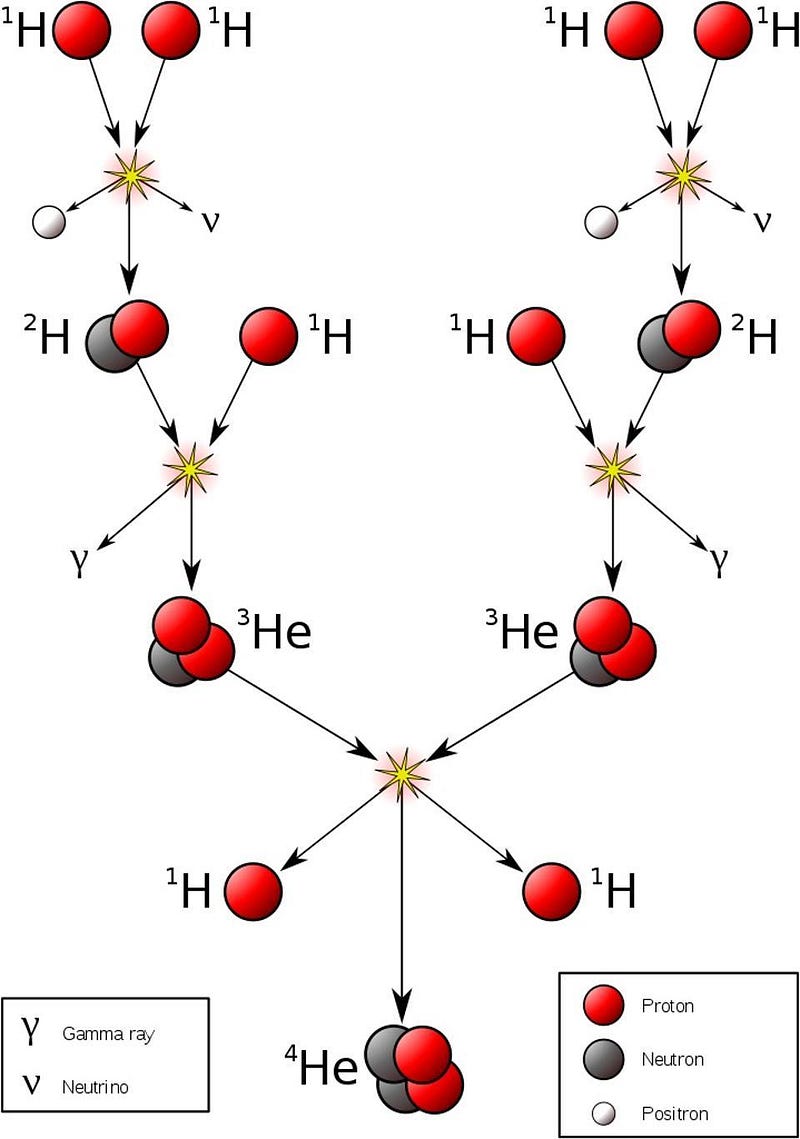

But once you start forming stars, everything changes. Yes, once you achieve star-like densities along with temperatures that rise over about 4 million K, you start fusing hydrogen into helium; our Sun is busy doing that right now. The nuclear processes that occur are literally Universe-changing. Only, they don’t just change things in the way we’d want; they also change things in an unexpected direction.

When you form a star, it isn’t just hydrogen that reaches those astronomically high temperatures, it’s all the particles inside. Unfortunately for lithium, these are temperatures that are more than sufficient to blast it apart. Lithium has been one of the most notoriously difficult elements to measure in the Universe for primarily this reason: by the time we arrive at the present day and can reliably extract a lithium signal, a lot of what the Universe began with has already been destroyed.

“Hang on,” I can hear you objecting. “The Universe is clearly full of these heavy elements: carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorous, and all the elements necessary for life, all the way up the periodic table to uranium and even beyond. Surely there’s got to be a way to make them, right?”

Indeed, you are right.

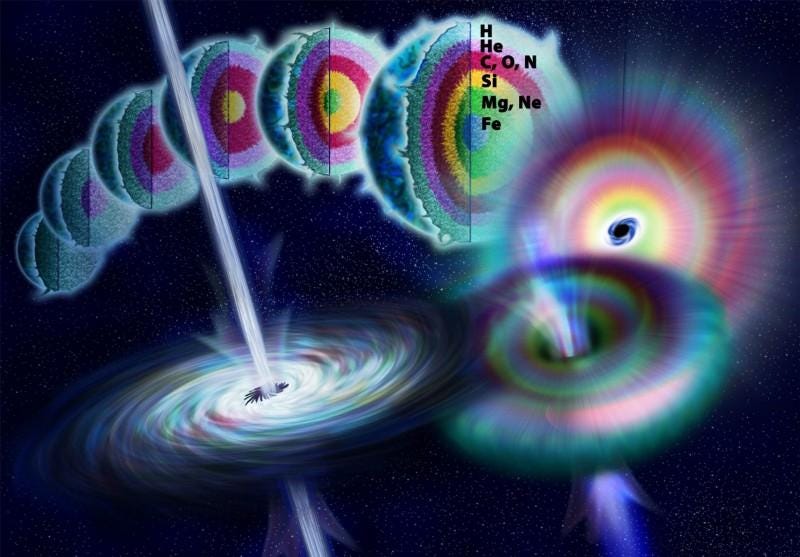

When every massive-enough star (including our Sun) burns through all the hydrogen in its core, nuclear fusion slows and stops. All of a sudden, the radiation pressure that was holding the star’s interior up against gravitational collapse begins to drop, and the core begins to shrink.

In physics, when any system of matter compresses quickly relative to a certain timescale, it heats up. In the interiors of stars, a mostly helium core can reach such extreme temperatures that the nuclear fusion of helium into carbon can begin, through a special nuclear reaction known as the triple-alpha process. In stars like the Sun, carbon is the end, and the only way heavier elements are formed is by the production of neutrons, which can bump you up the periodic table very slowly.

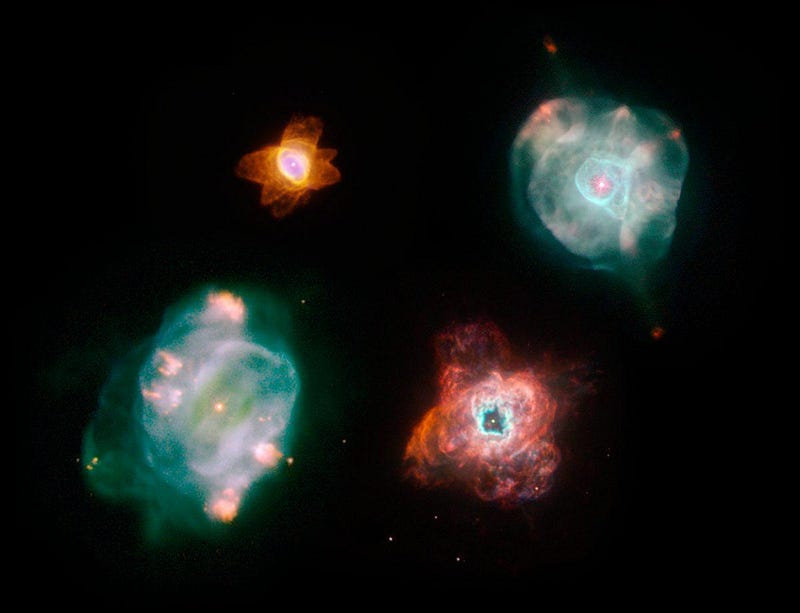

Once helium fusion has fully run its course, the star’s outer layers will be expelled in a planetary nebula while the core shrinks down to form a white dwarf.

But there are stars much more massive than this, capable of undergoing carbon fusion as the core contracts down even farther. Stars where this occurs will fuse carbon into oxygen, oxygen into neon, neon into magnesium, and up and up until they’ve created silicon, sulphur, argon, calcium, and elements all the way up to iron, nickel and cobalt. When they’ve finally run out of useful fuel, they’ll end their lives in a cataclysmic event known as a supernova.

These supernovae are responsible for a large fraction of many of the Universe’s heavier elements, while other events like white dwarf-white dwarf mergers or neutron star-neutron star mergers produce the remainder. Between stars that end their lives in planetary nebulae or supernovae, as well as the mergers of their remnants, we can account for the overwhelming majority of the elements found in nature.

Between the following mechanisms:

- the Big Bang,

- the hydrogen-burning stars,

- the helium-burning stars (complete with the emission and absorption of neutrons),

- the carbon-and-beyond-burning stars (complete with their end-of-life in Type II supernovae),

- the mergers of white dwarfs (producing Type Ia supernovae),

- and the mergers of neutron stars (producing kilonovae and the majority of the heaviest elements),

we can account for practically every one of the elements we find in the Universe. There are a couple of unstable elements that get skipped — technetium and promethium — because they decay away too quickly. But three of the lightest elements need a new method, because none of these mechanisms create beryllium or boron, and the amount of lithium we see cannot be explained by the Big Bang alone.

Hydrogen fuses into helium, and helium is element #2. It takes three helium nuclei to fuse together into carbon, where carbon is element #6. But what about those three elements in between? What about lithium, beryllium, and boron?

As it turns out, there are no stellar processes that make these elements in sufficient quantities without destroying them almost as quickly, and there’s a good physics reason why. If you were to add hydrogen to helium, you’d create lithium-5, which is unstable and decays almost immediately. You could try to fuse two helium-4 nuclei together to make beryllium-8, which is also unstable and decays almost immediately. In fact, all nuclei with masses of either 5 or 8 are unstable.

You cannot make these elements from stellar reactions involving light or heavy elements; there’s no way to make them in stars at all. Yet lithium, beryllium, and boron not only all exist, they’re essential to life processes here on Earth.

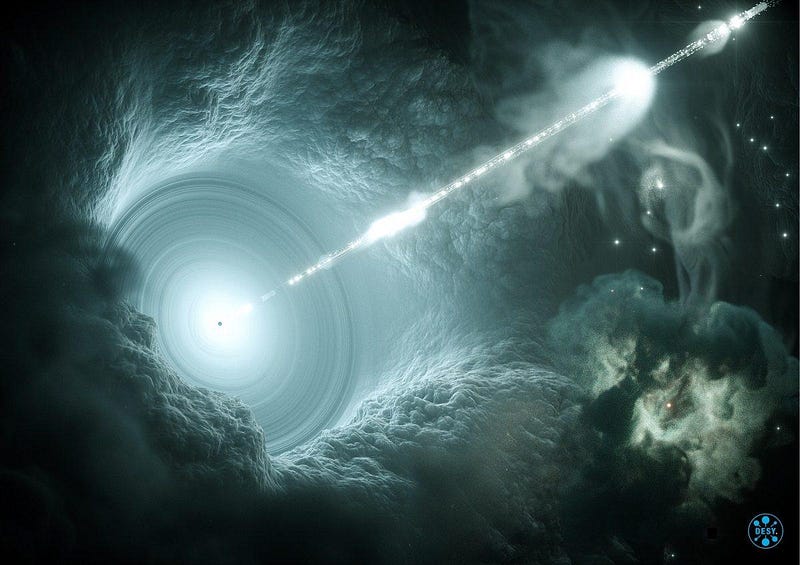

These elements, instead, owe their existence to the most energetic sources of particles in the Universe: pulsars, black holes, supernovae, kilonovae, and active galaxies. These are the Universe’s known natural particle accelerators, spewing out cosmic particles in all directions throughout the galaxy and even across the vast intergalactic distances.

The energetic particles produced by these objects and events move in all directions, and will eventually run into another particle of matter. If that particle that it strikes turns out to be a carbon (or heavier) nucleus, the high energies of the collision can cause another nuclear reaction that blasts the larger nucleus apart, creating a cascade of lower-mass particles. Just like nuclear fission can split an atom into lighter elements, the collision of a cosmic ray with a heavy nucleus can similarly blast these heavy, complex particles apart.

When you smash a high-energy particle into a massive nucleus, the large nucleus splits apart into a variety of component particles. This process, known as spallation, is how the majority of lithium, beryllium, and boron was formed in our Universe. These are the only elements in the Universe that are primarily formed by this process, rather than by stars, stellar remnants, or the Big Bang itself.

When you look at how abundant all of the elements we know of are, there’s a superficially surprising dearth of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th lightest elements of all. There’s an enormous gulf between helium and carbon, and at last we know why. The only way to produce these cosmic rarities is by a chance collision of particles streaking across the Universe, and that’s why there’s only a few billionths the amount of any of these elements compared to carbon, oxygen and helium. Cosmic ray spallation is the only way to make them once we’ve entered the age of stars, and billions of years later, even these trace elements are essential to the book of life.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.