Throwback Thursday: The Bad Math of the Biggest Loser

How the show most likely isn’t sending home the right people every week.

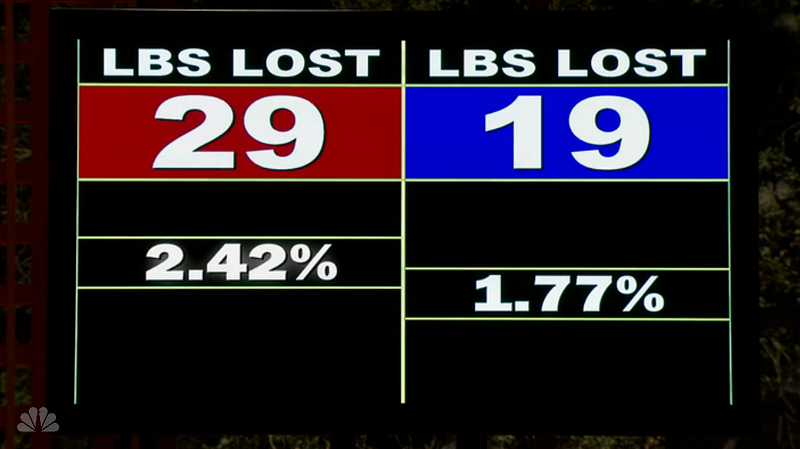

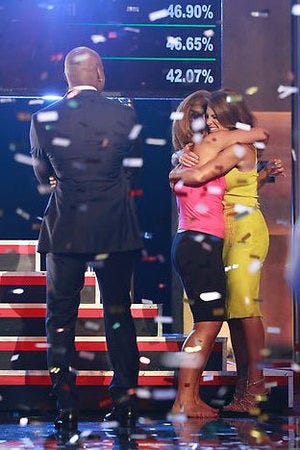

Image credit: NBC Universal / The Biggest Loser, Season 13 finale.

“Our external environment no longer seems to have any firm boundaries, any limits, or any positive cues about when to stop consuming anything. I mean, there is a reason that people get fat — it’s easy and cheap to get high-calorie, tasty food.” –Bob Harper

We all have guilty pleasures in life, the things we know aren’t good for us, but that we indulge in anyway. For me, one of those guilty pleasures is the TV Show The Biggest Loser, where morbidly obese contestants participate in a reality weight-loss show, where the end goal is to lose the greatest percentage of your original body weight. At the end of the season, the show’s “Biggest Loser” wins a huge sum of money, the title of the Biggest Loser and the chance to have a bunch of confetti rain down on them.

Now, I know that incredibly rapid weight loss — achieved by a combination of extreme dieting and extreme exercise — is not a sustainable plan for a long-term, healthy permanent lifestyle. But the opportunity to train full-time with a professional personal trainer and to have a chance at winning $250,000 (up from $100,000 in early seasons) makes it seem a lot more appealing! The catch, and there’s always a catch, is that you have to avoid having the lowest percentage of weight loss every week.

Those are just the rules of the game: sometimes it’s the team with the lowest percentage of weight loss that has to vote someone home, sometimes it’s the two people with the lowest individual percentages of weight loss that have to be voted on for elimination, and sometimes it’s simply the individual whose lost the lowest percentage of weight that week who goes home.

I don’t really mind setting arbitrary rules for a competition like this, but the thing that infuriates me about watching the show is that the way they measure “percentage of weight lost” potentially sends the wrong person home a large amount of the time.

Take last week on the Biggest Loser, for example.

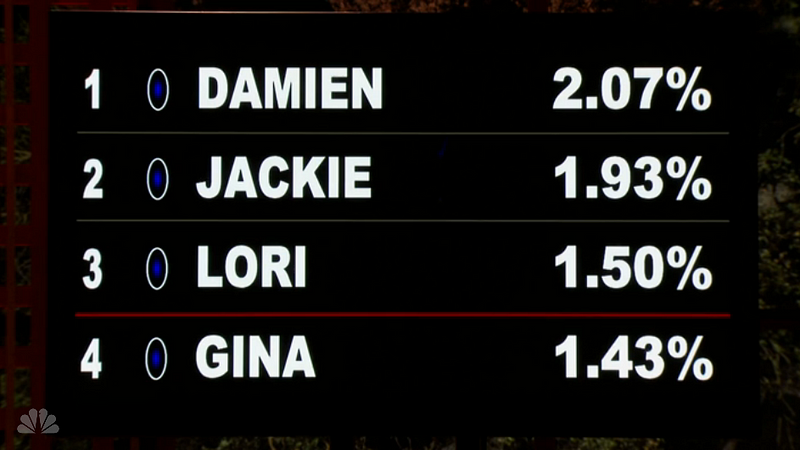

The blue team lost the weigh-in, having lost a lower percentage of weight than the other two teams, meaning that the person on the blue team who lost the smallest percent of their previous weight would have to go home.

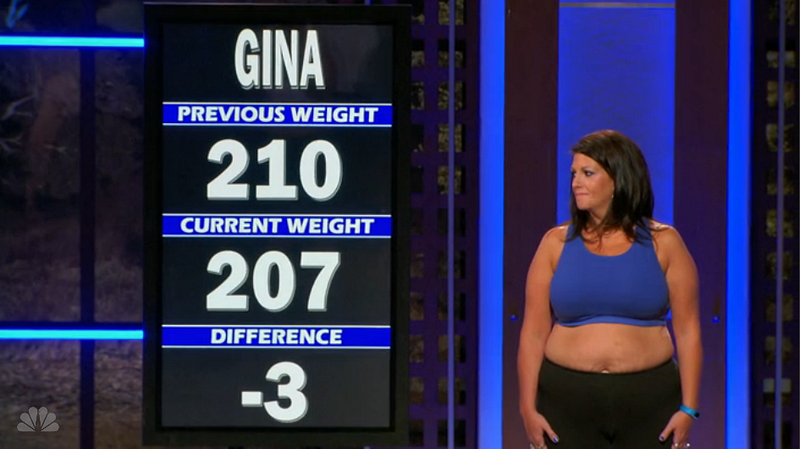

According to the math of the show, that person was Gina. Sorry, Gina.

But did Gina really lose the least amount of weight on her team? Let’s go back to Gina’s weigh-in and examine this.

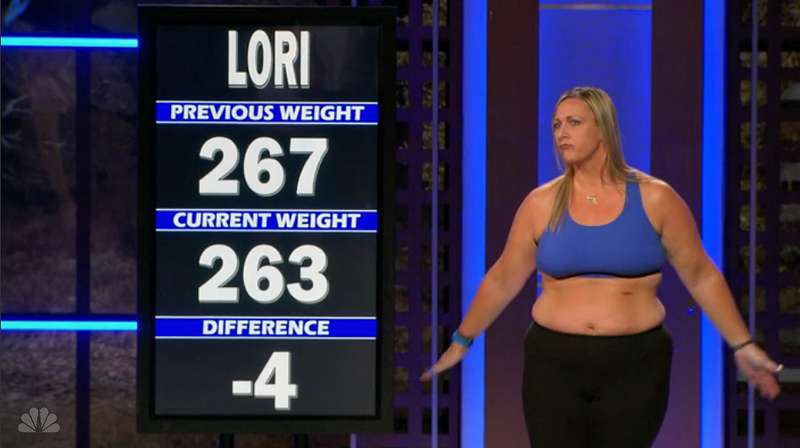

According to the scale, Gina lost 3 pounds from the prior week. This was still pretty good, considering she had lost 7 pounds the week before, and considering she only weighed 210 pounds going into the weigh-in. But losing three pounds when you weighed 210 means she had a percentage weight loss of 1.43%. Now, that’s clearly a smaller number than 1.50%, which is what Lori — the next closest competitor on her team — had lost.

Lori had lost 4 pounds from the prior week, which she had begun at 267 pounds. And that makes sense according to this math: 3 ÷ 210 is a smaller number than 4 ÷ 267, so Gina deserved to go home.

Or did she?

This is a big problem that shows up for scientists and science students all across the country, from the research lab to college to high school to even middle and primary school: your results are only as reliable as the precision and accuracy to which you measure them.

When the scale says that Gina had lost 3 pounds, it doesn’t mean that Gina lost 3.0 pounds or 3.00 pounds, it only tells us that Gina lost somewhere between 2.500 pounds and 3.499 pounds. In other words, we can only conclude that the amount of weight Gina lost was closer to 3 pounds than it was to either 2 pounds or 4 pounds.

And when the scale says that Lori had lost 4 pounds, it doesn’t mean that Lori lost 4.0 pounds or 4.00 pounds, it only tells us that Lori lost somewhere between 3.500 pounds and 4.499 pounds. In other words, we can only conclude that the amount of weight Lori lost was closer to 4 pounds than it was to either 3 pounds or 5 pounds.

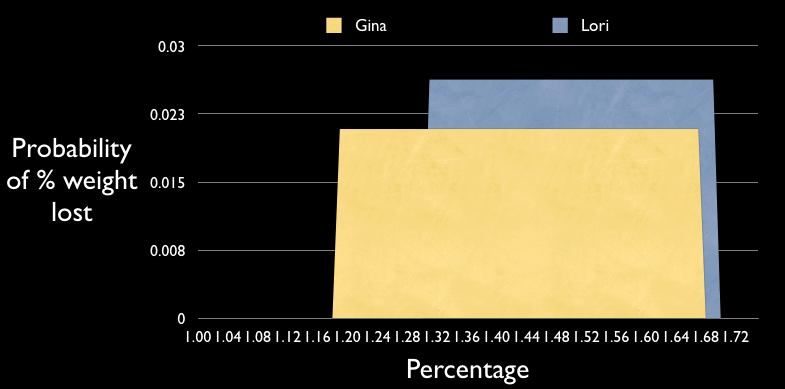

But in reality — assuming that their starting weights were exact — we can only say the percentages they lost fell somewhere within the following range:

We know that Gina lost somewhere between 1.19% of her weight and 1.67% of her weight, and we know that Lori lost somewhere between 1.31% and 1.69% of her weight. This is the problem that scientists refer to as not having enough significant digits in your data.

Could we decide who actually lost more? Sure we could! There’s only one thing we’d need to make that happen: we’d need a better scale.

If we knew that Gina lost 2.67 pounds and Lori lost 4.23 pounds, then Gina should definitely have gone home. But if Lori had lost 3.60 pounds and Gina had lost 3.10, then it should have been Lori who lost. Even getting the precision down to a tenth or even a quarter of a pound would help tremendously when it came to making sure the right person went home (or stayed on) according to the rules of the show.

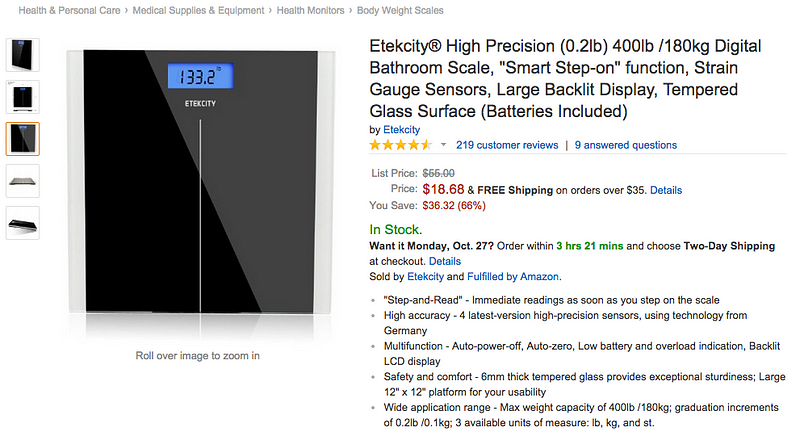

The thing is, I don’t know why The Biggest Loser does it this way; you can get a more accurate scale — one that measures to 0.2-pound precision and holds weights up to 400 pounds — for less than $20.

On a week-to-week basis, this is bad enough. But when season 14 aired, the finale was so close that the winner — Danni — would have lost to Jeff if she had lost one fewer pound, meaning that this very practice of rounding off the results to the nearest pound may have awarded $250,000 to the wrong person!

And so I’ll continue to enjoy my guilty television pleasure, but I’ll have to do it with extra fist-shaking every week, knowing that on any given week, the wrong person could be going home simply because the show’s producers were too lazy to use a more accurate scale.

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!