How an “underwater waterfall” came to exist on Mauritius

- About 2000 miles off the eastern coast of Africa lies a chain of islands, with the largest of them known as Mauritius, inhabited by over 1.2 million people.

- Formed by a volcanic hot spot in the Indian Ocean, Mauritius is home to its own unique flora and fauna, an enormous series of coral reefs, and a spectacular sight: an underwater waterfall.

- Although you might think the notion of an “underwater waterfall” is impossible, there’s a compelling physical explanation behind this stunning phenomenon.

Although most of the land masses on Earth are present in the well-known form of continents, there are a few exceptions to that rule. In a few select locations, even surrounded by ocean waters that can sink to depths of multiple miles or more, land masses emerge, compelled upwards by the eruptive volcanic forces springing forth from Earth’s mantle. These geological hotspots frequently create oceanic islands and/or chains of islands, with some of the more famous ones including the Hawaiian Islands, American Samoa, and the Galapagos Islands.

However, a less-widely known set of oceanic islands is found about 2000 miles east of the eastern coast of Africa. Beneath the water’s surface, a submarine plateau persists, known as the Mascarene Plateau. In a few select locations, such as the Seychelles to the north and the Mascarene Islands to the south, the volcanic features have led to the emergence of land masses, poking up above sea level and have been inhabited by humans for centuries. The second largest of the southern islands, Mauritius, is not only one of the most beautiful natural locations on Earth, but also has one striking feature that’s unparalleled: what appears to be an underwater waterfall. Here’s the science behind this fascinating phenomenon.

The first thing you have to recognize is that a submarine plateau, in general, has a series of features specific to it that are very different from what continent-dwellers are used to. On a continent, you have a large land mass that very, very gradually transitions into deep ocean waters. Surrounding the land masses on all sides are continental shelfs where the water is, at most, a few hundred feet (or up to around ~150 meters) deep. You have to travel a substantial distance away from the land mass to reach the edge of the continental shelf, where finally the transition to deep ocean waters — tens of thousands of feet (and thousands of meters) down — occurs.

By contrast, on a submarine plateau, the islands that are found on the borders of the plateau might have those typical continental-shelf depths on two or three sides, but the remaining side(s) can experience an almost immediate plunge into deep ocean waters. Instead of going from dry land into shallow waters, it’s possible to take a casual swim where, after only a few minutes, you find yourself in waters that extend down to a depth of thousands of meters.

The entire southern half of the Mascarene Plateau is one of the newest major features on our planet, having only been created over the most recent few million years. The Réunion hotspot, which for some reason went relatively quiet about ~45 million years ago, became active about 10 million years ago. The emergence of lava from the bottom of the seafloor created all of the Mascarene Islands in the geological blink-of-an-eye.

Mauritius, where this unusual “underwater waterfall” exists, was created about 8 million years ago, and is the second-largest of the Mascarene Islands. The largest island, Réunion, is even more recent: created about 2 million years ago, it contains one of the most active volcanoes in the world. Wherever you have a shallow-water shelf around these islands, you have an abundance of tropical life, thriving in the coral reefs found there. But in the locations where there’s a deep-water plunge, not only are the flora and fauna vastly different, but the water itself has an appearance that presents a stark contrast to the shallows.

That’s expected; the reason the ocean is blue is not, as people commonly state, because it reflects the sky. Even though the sky really is blue of its own volition, its appearance has nothing to do with the blue color of Earth’s oceans. Water, just like the atmosphere, is made out of molecules of a finite size, and those molecules are much smaller than the wavelengths of any light that our eyes can detect. But unlike the atmosphere, where the scattering of visible light causes its color, the reason liquid water takes on a color is because of absorption.

Water is excellent at absorbing light of certain wavelengths, including:

- infrared radiation,

- ultraviolet light,

- and red visible light.

This means, when you head down to even a modest depth, you’re well-protected from ultraviolet radiation, you won’t feel the Sun’s warmth on your skin, and things will start to turn blue. As you go progressively deeper, the orange colors go away next, followed by the yellows, greens, and violets. It isn’t until you get down to a depth of multiple kilometers that blue light, the last set of wavelengths of visible light to get absorbed, go away entirely.

This means that the deeper the waters are, the deeper the blue color that you’ll see. When you have solids or liquids that enter into that water, whatever is less dense will “float” atop the typical-density waters, while whatever is denser will sink down below the typical-density waters.

You might immediately start asking yourself, “is that true even if the thing you’re adding into the water is other water?”

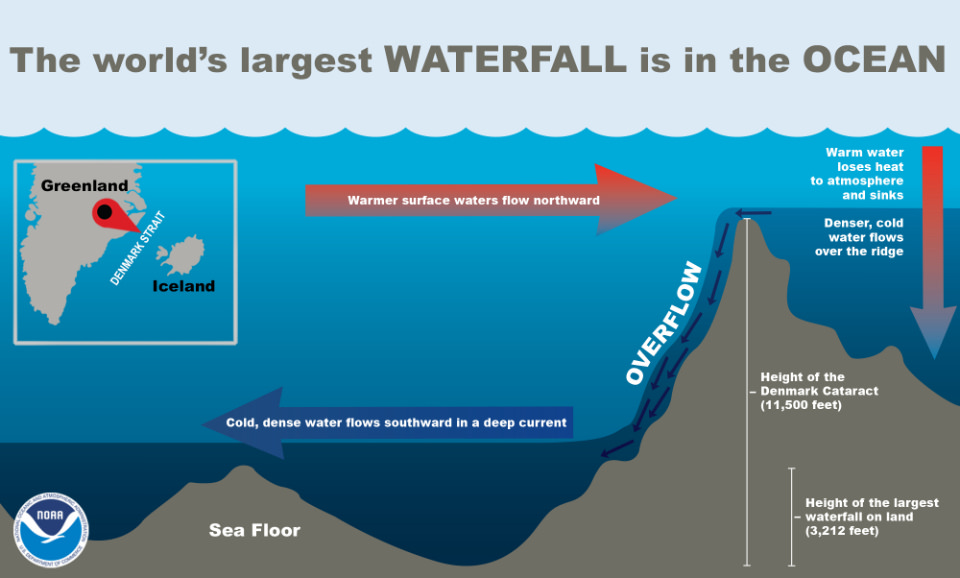

The answer, surprising to some, is yes. The largest example in the world is the Denmark Strait Cataract, located in the Arctic Circle in the waters between Greenland and Iceland. The waters on the eastern side of the strait — the Iceland side — are significantly colder than the waters on the western side. Since water reaches its maximum density at near-freezing temperatures of 4 °C (39 °F), the colder eastern waters, with temperatures of only 2 °C (35 °F) or lower, are significantly denser than the warmer western waters, and sink beneath them where the two water masses meet.

The Denmark Strait Cataract is the world’s highest underwater waterfall, where the cold water sinks down a shocking 3.5 kilometers, or more than two miles.

But that type of underwater waterfall, despite the extreme rate of fluid flow it creates, is fundamentally different from what’s happening in Mauritius. First, because water is simply water, an underwater waterfall of “water flowing into water” isn’t exactly visible; the human eye wouldn’t be able to detect it.

And second, what’s happening on Mauritius isn’t an example of “water flowing into water,” which is what most people think of when they envision an underwater waterfall. Instead, there’s:

- no significant temperature gradient,

- no continuous flow of water from higher depths to lower depths,

- and no situation where multiple sources of water are meeting.

What’s driving Mauritius’s amazing underwater waterfall is something else entirely.

The surprising culprit, and the cause of this striking phenomenon?

It’s sand.

That’s right: what’s happening is nothing more complicated than erosion, the same process where flowing water and air weather away the coastal regions, grinding a solid land mass into tiny, grain-sides fragments. The volcanically formed island of Mauritius has copious amounts of sand on its coast, and ocean currents move that sand back-and-forth over the shallow shelves that border the island.

However, where the shallow shelves that are part of this submarine plateau end, there are only deeper, bluer, darker waters. And when the ocean currents drive that coastal sand off of the southern tip of Mauritius and into the deep ocean waters, what appears to be an “underwater waterfall” is actually the result of sands sinking through the deep water, down to the bottom of the ocean.

There are many horseshoe-shaped waterfalls in existence, with perhaps the most famous ones being the Canadian side of Niagara Falls and the spectacular Icelandic waterfall Goðafoss — the “Waterfall of the Gods” — shown above and below, respectively.

It’s perhaps for that reason, when we see something that’s visually similar, even when it occurs underwater, our minds immediately take us to the conclusion that we’re seeing a waterfall.

Even so, the underwater waterfall off the southern coast of Mauritius is truly a one-of-a-kind phenomenon, as the erosion that’s occurring is particularly directional. There’s a horseshoe-shaped crevasse at the very end of the underwater plateau, leading to deep ocean waters below.

As the sand gets swept, via ocean currents, off of the shallow shelf and into that crevasse, that familiar sight we associate with waterfalls appears quite prominently, showcasing the power of flowing water and the fragile nature of small land masses at the same time.

Although Mauritius, like its neighboring large island Réunion, has over 2,000 square kilometers of land area, and a population of right around one million human inhabitants, it’s unlikely that it will remain an above-sea-level island for very long. Even the longest-lived volcanic islands, found where the largest volcanic plumes occur over the slowest-moving tectonic plates, only persist for a few tens of millions of years, at most.

The island of Mauritius stopped growing long ago and is in the process of being eroded away, until it becomes nothing more than a ridged section of the greater undersea plateau. This is neither a bug nor a feature, but rather just one more example of the transient nature of all geological structures on Earth. Even though it’s caused by the motion of sand from shallow waters into deeper ones, the “underwater waterfall” off of the southern coast of Mauritius is sure to remain a spectacular natural wonder for millions of years to come.