Why 2023’s Venus-Jupiter conjunction won’t be bettered until 2039

- As the third planet from the Sun in our Solar System, five other planets are clearly visible to even the naked human eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

- The brightest planet from Earth is Venus, while Jupiter is usually second-brightest. Every once in a while, including in early March, 2023, these two planets align in the skies: creating an astronomical conjunction.

- Yet we won’t get another conjunction of the two brightest naked-eye planets that’s this easily visible until 2041. Here’s the surprising science of why.

Like clockwork, the planets dance in the night sky, passing one another in predictable, repeating orbits: a dance that’s been ongoing continuously for billions of years. Even despite the effects of General Relativity and the gravitational influence of the other planets on one another, the simple laws of planetary motion that date back to Kepler dictating how quickly the planets move, in ellipses around the Sun, relative to one another are so perfect that they require no corrections over the timescale of many centuries to successfully predict where, at any given time, the planets will appear relative to one another.

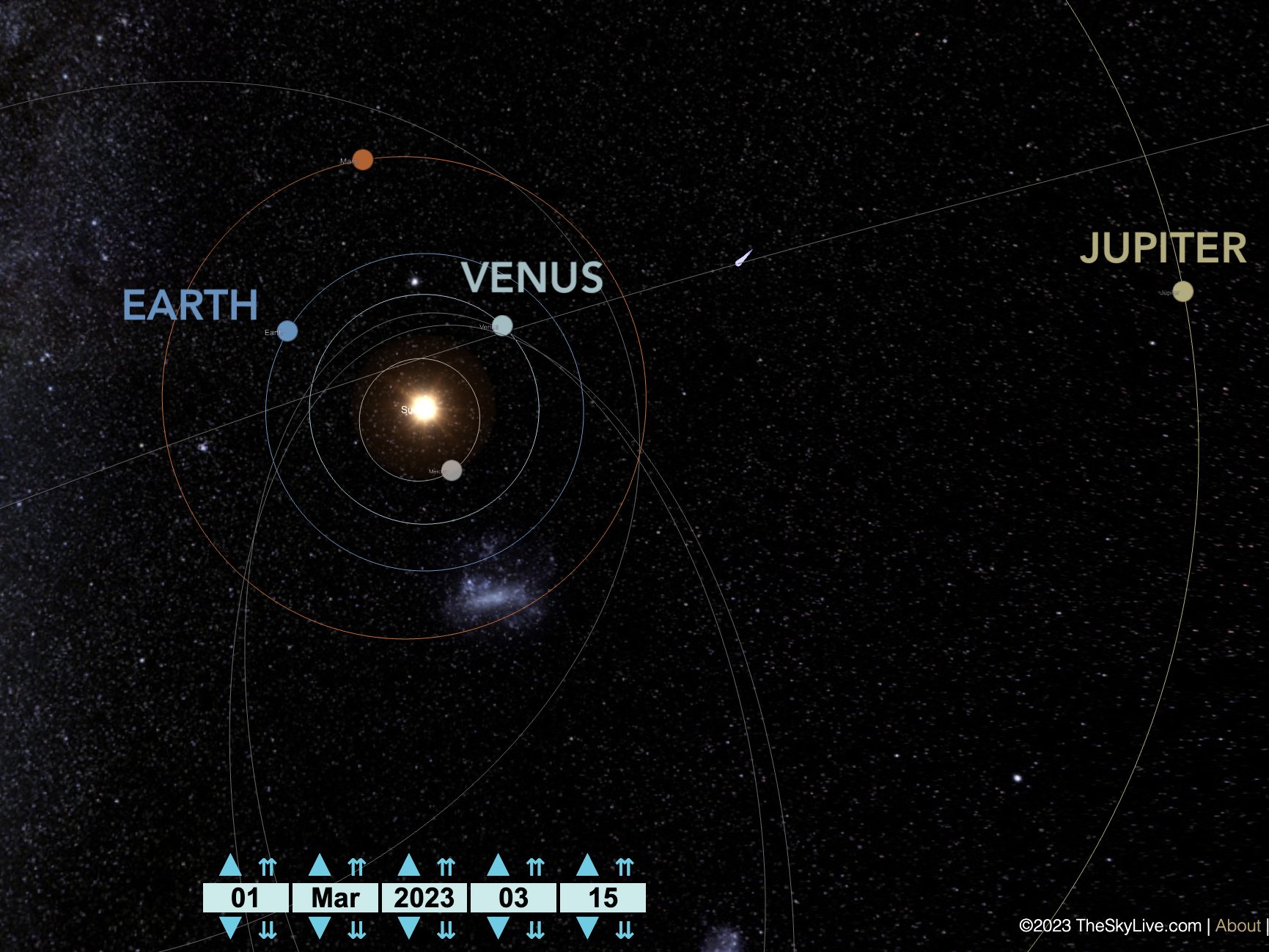

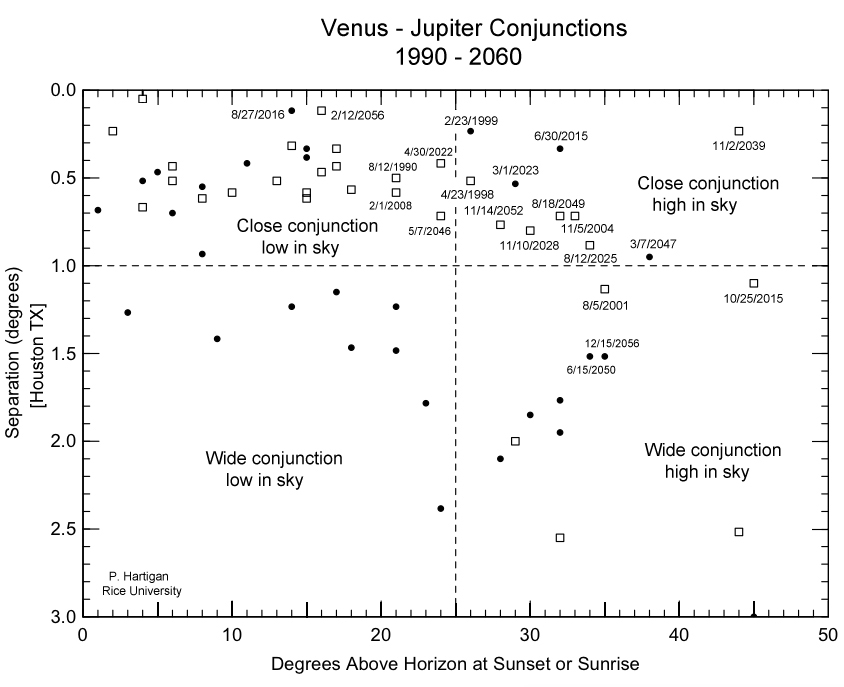

On March 1st and 2nd, 2023, Venus and Jupiter will align in a spectacular conjunction: an astronomical event where the two brightest planets in Earth’s night sky will be separated by merely half-a-degree, or about half the width of your pinkie finger’s nail when you hold it at arm’s length. Easily visible in the post-sunset skies if you have a clear western horizon, this marks the closest, most easily visible meeting of our two brightest planets since 2015, and there won’t be a better show until 2039. Here’s a guide to what you can see and the science of why, plus what you can do to make the most of this and all future conjunctions.

Even on its own, Venus is a remarkable planet and served up one of the strongest pieces of evidence against the old geocentric model when Galileo first turned his astronomical telescope skyward in 1609/1610. To the unaided human eye, Venus is simply a bright point of light: the brightest natural object to appear in Earth’s skies behind only the Sun and Moon. Although its brightness changes by a little bit (about half-a-magnitude) with about a 20 month period, Venus’s more notable property is that it regularly changes positions quite rapidly in our skies, and is alternately known as “the morning star” or “the evening star” dependent on when and where it appears.

As the brightest planet in our skies, Venus is often the first “light” you see once the Sun goes down. Whenever the Sun sets (due to the Earth’s rotation) and Venus is to the East (left) of the Sun, it appears in the evening skies. Similarly, it’s often the last “light” that remains from the night when the Sun rises. Whenever the Sun rises (due to the Earth’s rotation) and Venus is to the West (right) of the Sun, it appears in our morning skies. Venus reaches its farthest from the Sun — its greatest elongation — about 71 days before (for the “evening star”) and after (for the “morning star”) it achieves maximum brightness. However, it was being able to see Venus through a telescope that truly explained what was happening.

Quite clearly, Venus exhibits a full suite of phases: from new to a waxing crescent to a half-full phase to a waxing gibbous to a full phase and then back again, waning through a gibbous, half-full, and crescent phase before returning to a new phase once again. Additionally, Venus never ventures very far from the Sun as seen from Earth. Whereas Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn could appear anywhere in the night sky, even diametrically opposed to where the Sun would be, Venus and Mercury are restricted in how far they could travel: Venus never gets more than 47° from the Sun, and Mercury never gets more than 23° away from it.

Why would this be happening?

Such observations could only be possible if both Venus and Earth orbited the Sun, and if Venus were an interior planet to Earth. As one of only two planets (along with Mercury) to display the new, crescent, and half-full phases as seen from Earth, this definitively showed how heliocentrism could explain phenomena that geocentrism could not. Venus and Mercury orbited the Sun interior to Earth, while the other planets — Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn — had to orbit more distantly. But despite its slow and outer nature, Jupiter was arguably even more convincing in its support for heliocentrism.

That’s because, when you examine Jupiter through a telescope, sure, it always looks roughly spheroidal, but Jupiter has its own prominent satellites that appear even in a very small telescope or a pair of conventional binoculars. In fact, Jupiter has four large satellites — its Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — that lie just below the visibility limits of human vision. Over time, these four objects can easily be seen to orbit Jupiter, following a counterclockwise orbit around their parent planet, just as all the planets orbit counterclockwise about the Sun.

With the discovery that other planets (not solely the Earth) possessed moons, it was clear that whatever “force” was keeping the planets moving around the Sun and that kept the Moon in orbit around the Earth was also at play around other planets, and moons around other planets (such as Saturn) would follow later than century.

Part of the beauty of a close conjunction of Venus with Jupiter is that you can see both phenomena — Venus’s phases and Jupiter’s moons — in the same field-of-view with a pair of binoculars or a telescope. It’s a rare sight that only comes along once every several years!

But that statement, particularly if you’re familiar with astronomy, astrophysics, and the laws of gravity, might puzzle you when you hear it. After all, Earth completes a revolution around the Sun once a year, and the analogy that “planets move like clockwork” has been around for as long as we’ve recognized just how unbearably regular planetary orbits are.

Sure, Jupiter is on an outer orbit, causing it to move much more slowly than Earth does around the Sun. Whereas Earth makes a full revolution around the Sun once a year, it takes Jupiter more like 12 years to move around the Sun. As a result, the Earth, Jupiter, and the Sun return to their same relative positions in the sky once every 13 months.

Similarly, Venus is on an inner orbit to Earth; it takes only about 8 months to complete a revolution around the Sun. In fact, for every 8 orbits around the Sun that Venus completes, Earth completes 5 of its own, which is where we get the figure that it takes 20 months for Venus, Earth, and the Sun to return to the relative positions they’re in right now. These planetary motions have been known for many centuries, and are disputed by pretty much no one.

And yet, the March 1/2, 2023 conjunction of Venus and Jupiter was preceded by earlier conjunctions from:

- April 30, 2022,

- August 27, 2016,

- June 30, 2015,

- February 1, 2008,

- and November 5, 2004.

This represents all of the close conjunctions (within 1 degree or less) that have occurred between Venus and Jupiter since the dawn of the 21st century. The 2022, 2008, and 2004 conjunctions occurred in the pre-dawn skies, while the 2015, 2016 and 2023 conjunctions took place in the post-sunset skies.

But if Venus-and-Earth return to the same relative positions every 20 months, and Jupiter-and-Earth return to the same relative positions every 13 months, then shouldn’t there be many more conjunctions of Venus and Jupiter than we’re documenting here?

You might expect that, and you’d have every reason to make such a forecast. But there are two factors that work against those expectations, and we cannot ignore them if we want to predict the motions of the heavenly bodies and the occurrences of their conjunctions correctly.

The first thing you have to realize is that all of the planets don’t truly orbit in precisely the same plane. We can start by defining the plane that Earth’s orbit defines as it revolves around the Sun: the ecliptic plane. If you slid a sheet of paper (or any other two-dimensional surface) through the Sun and oriented it so that Earth always orbited along that plane, you would find that orbits of the other seven planets were inclined to that plane, as each individual planet has its own unique orbit around the Sun. Compared to the ecliptic plane defined by the Earth-Sun orbit, the inclinations of the other planets are:

- Mercury, 7.01°,

- Venus, 3.39°,

- Mars, 1.85°,

- Jupiter, 1.31°,

- Saturn, 2.49°,

- Uranus, 0.77°,

- and Neptune, 1.77°.

Relative to the Earth-Sun plane, then, Venus can appear up to 3.39° either above or below that plane, while Jupiter can appear up to 1.31° either above or below that plane. While there are many Jupiter-Venus conjunctions that will occur where the two planets are located within 1° or even 0.5° (or less) away from one another, a large number of these conjunctions — nearly about half of them — occur with separations that are greater than 1°. Many Jupiter-Venus conjunctions, in other words, don’t actually bring the two planets particularly close to one another, at least, as seen from Earth.

But what’s even more impactful is this: most of the conjunctions that occur between Venus and Jupiter are not visible by human observers located on the surface of the Earth.

In other words, conjunctions truly are far more frequent than leap years are; in fact, they occur roughly annually, on average. But conjunctions that are actually visible from Earth are much more rare, because most of the ones that occur aren’t visible for a simple reason: you can’t see planets with your naked eye during the day.

In fact, the sky has to darken quite substantially once the Sun goes down (or has to remain dark before the Sun comes up) if you want to see a planet that’s close to it. Yes, Venus never ventures more than 47 from the Sun, but during most of the time, Venus appears much closer to the Sun than that. During 50 days out of every 20 month interval, Venus is behind the Sun, and is invisible from Earth entirely. Similarly, Venus spends 8 days out of every 20 month interval in between the Earth and Sun, rendering it equally invisible. Only when Venus is either approaching the Earth from behind or receding from the Earth after recently passing it is it visible, and during most of the time, is in the teens-to-20s of degrees from the Sun.

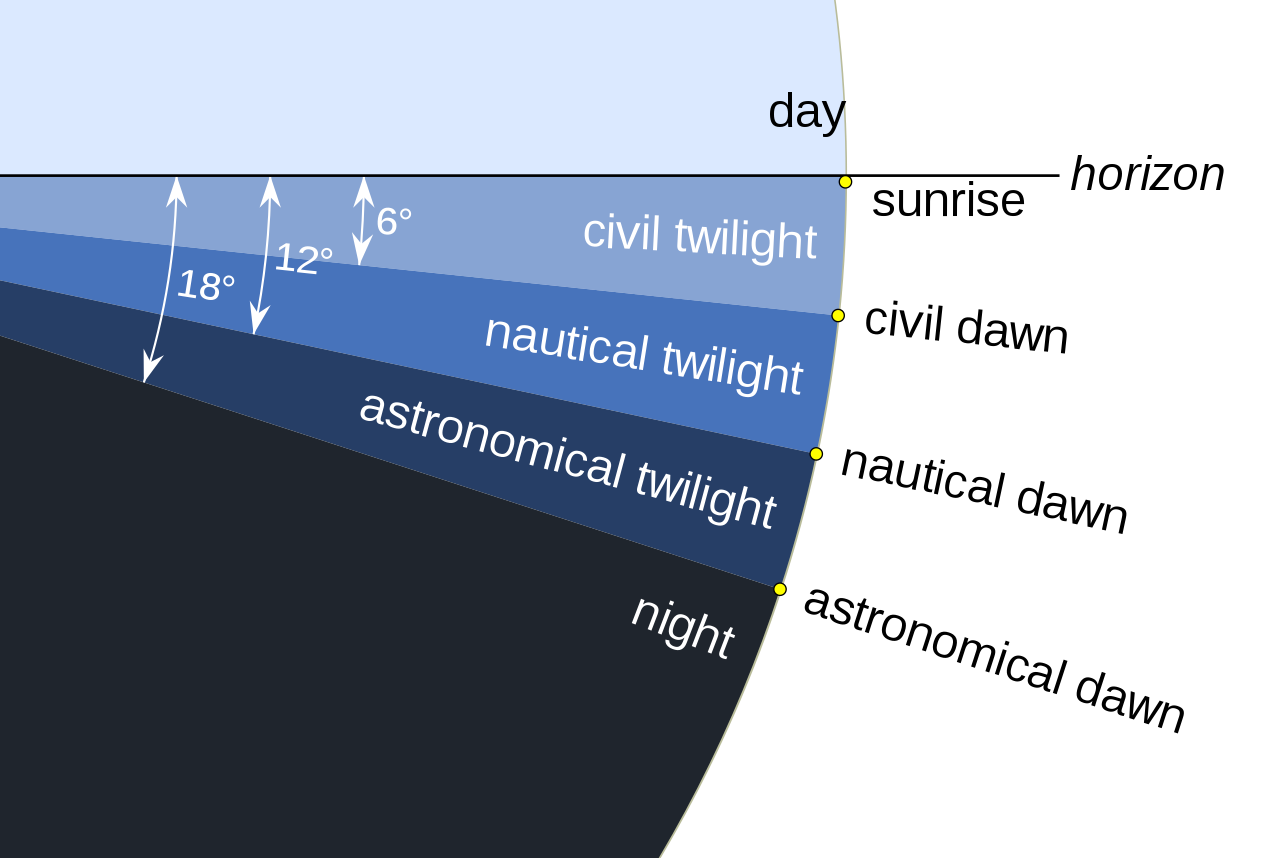

Now, here’s where we can really see why visible conjunctions of Venus and Jupiter are so rare: unless a conjunction occurs where the planets are more than 18°-to-20° from the Sun, you simply won’t be able to see them from Earth. Astronomers normally divide the post-sunset and pre-dawn portions of the night into four categories, depending on how low below the horizon the Sun actually is.

- 0° to 6°: civil twilight, where no artificial light is needed for full visibility and no planets or stars are generally visible.

- 6° to 12°: nautical twilight, where the sky starts to considerably darken and where only bright stars and planets not located near the Sun itself (i.e., so that they won’t be lost in the Sun’s glare) are visible.

- 12° to 18°: astronomical twilight, where observers making a special effort can see bright objects (like stars and planets) that are located very close to the horizon, even though the Sun’s glare will pose a substantial obstacle.

- And more than 18°: full-on night, where stars and planets are visible everywhere they appear, even at the horizon.

Additionally, especially at higher (non-equatorial) latitudes, the Sun typically both goes below and rises above the horizon at an angle, meaning that it may take more than 60-90 minutes after sunset (or before sunrise) to achieve dark skies. If the objects you’re interested in are below the horizon during that time, you simply won’t see them. As a general rule-of-thumb, the best “hunting time” for these planets occurs when their separation from the Sun is 25° or greater.

Most conjunctions of Venus and Jupiter occur during these unfavorable viewing conditions: too close to the Sun to be seen by humans on Earth. Additionally, very close conjunctions, where Venus and Jupiter are separated by 0.5° or less, are extremely rare, especially when taken as a subset of easily visible Venus/Jupiter conjunctions.

The March 1/2, 2023 conjunction is special because Venus and Jupiter are separated by only 0.5° while the Venus/Jupiter pair is separated from the Sun by 25° or more. (Specifically, this conjunction has a separation of 29°.) From 1990-2060, the only other dates that have such a close conjunction with such a large separation are:

- April 23, 1998 (pre-dawn), with a 0.5° conjunction and a 26° Sun separation.

- February 23, 1999 (post-sunset), with a 0.2° conjunction and a 26° Sun separation.

- June 30, 2015 (post-sunset), with a 0.3° conjunction and a 32° Sun separation.

- And September 2, 2039 (pre-dawn), with a 0.2° conjunction and a 39° Sun separation.

If you want to see Venus and Jupiter at their closest, you’ll have to make a very special effort to combat the horizon. The February 12, 2056 pre-dawn conjunction will have Venus and Jupiter separated by only 0.1°, but at just 16° above the horizon, it’ll be a supreme challenge. On November 22, 2065, Venus will actually occult Jupiter: passing in front of it for our first planet-planet occultation since 1818, but only 8° above the horizon. Planets routinely make close approaches, but in order for humans to see and enjoy it, it takes a far rarer confluence of circumstances.

Enjoy the sights we have when we have them, and may your attempts to enjoy the Universe be met with clear, dark skies!