Ask Ethan: What explains the Fibonacci sequence?

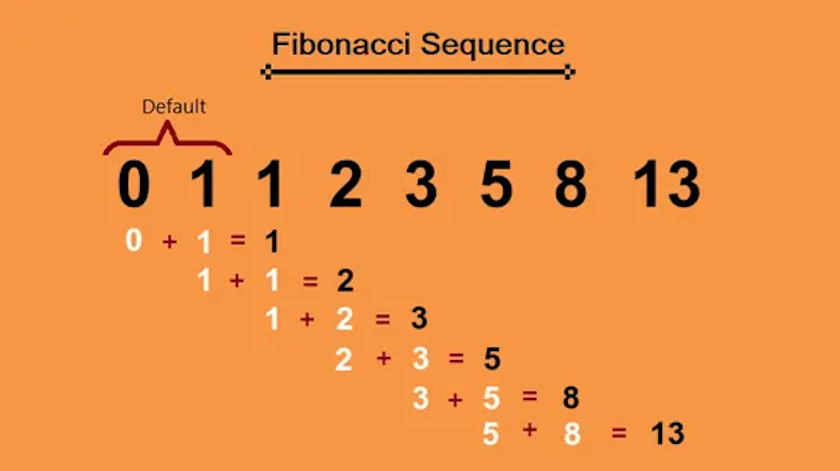

- If you start with the first two numbers in a sequence as “1” and “1,” you can add them together to make the next number, “2,” and then add that new number to the prior number to make the next one.

- Named after the Italian mathematician, Leonardo of Pisa (better known as Fibonacci), these numbers often appear in mathematics, computer science, and even nature itself.

- Even though it doesn’t explain every “spiral” or recurring and progressive structure, it does explain a lot. Its mathematical roots, however, are both simpler and more complex than you might imagine.

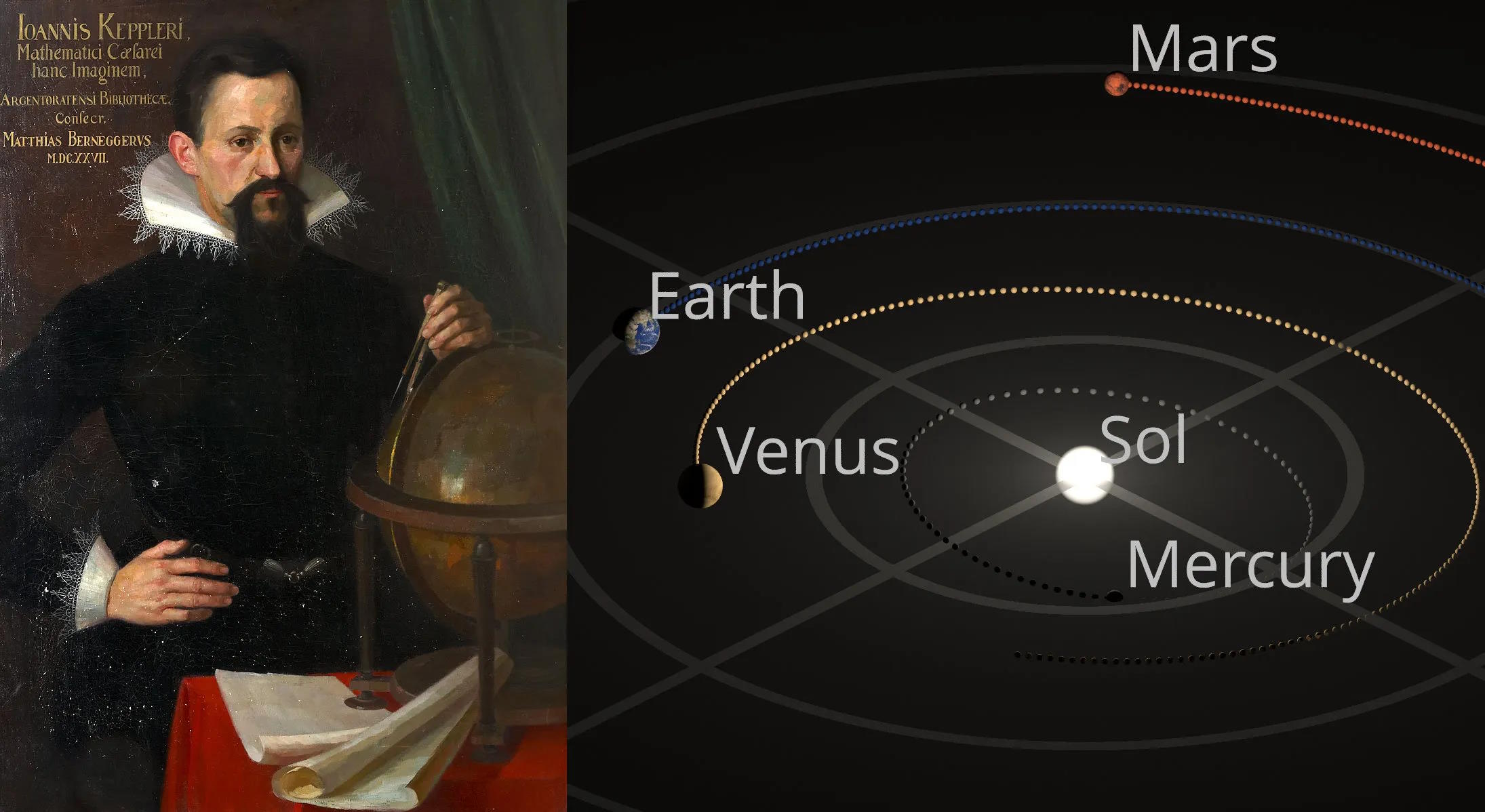

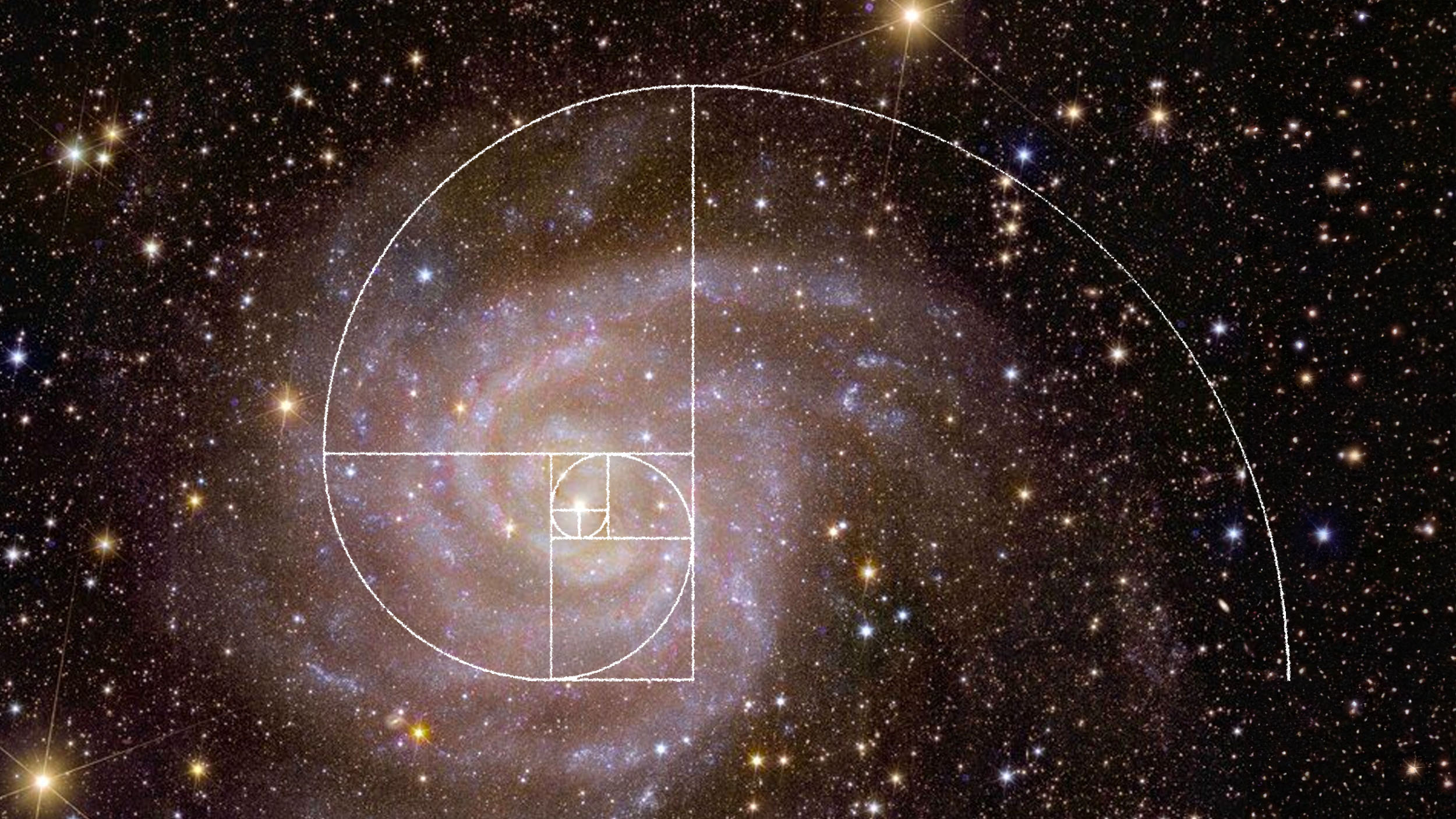

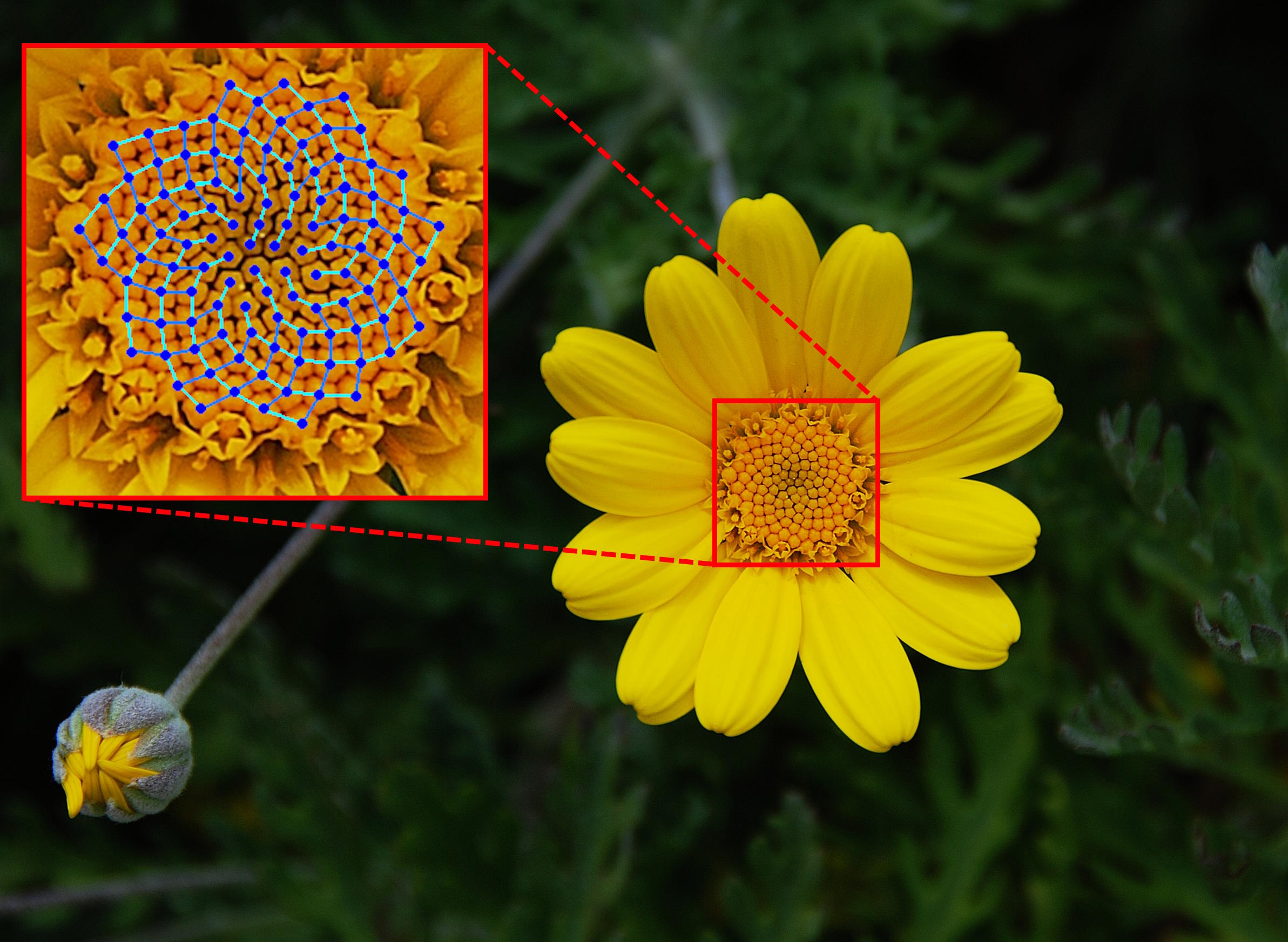

One of the most fascinating facts about the natural world is that so many entities within it — both biologically and purely physically — obey a specific set of patterns and ratios. Many galaxies exhibit spiral shapes and structures, as do a wide variety of plant structures: pinecones, pineapples, and sunflower heads among them. Ammonites, shelled animals that went extinct more than 60 million years ago, also show that spiral pattern, where one of the key features of spirals is that the next “wind” around outside the prior one displays a specific length ratio to the size of the prior, interior winding.

That ratio, in any such structure, is often extremely close to the ratio of two adjacent numbers found in the Fibonacci sequence. This mathematical sequence, often taught to children, simply starts with the numbers “0” and “1” and then gets the next term in the sequence by adding the two prior terms together. It’s arguably the most famous mathematical sequence of all, but what explains the sequence’s pattern, and is it truly, inextricably linked to nature? That’s what Ragtag Media wrote in to ask, inquiring:

“Is there a Fibonacci sequence with regards to the way galaxies develop?”

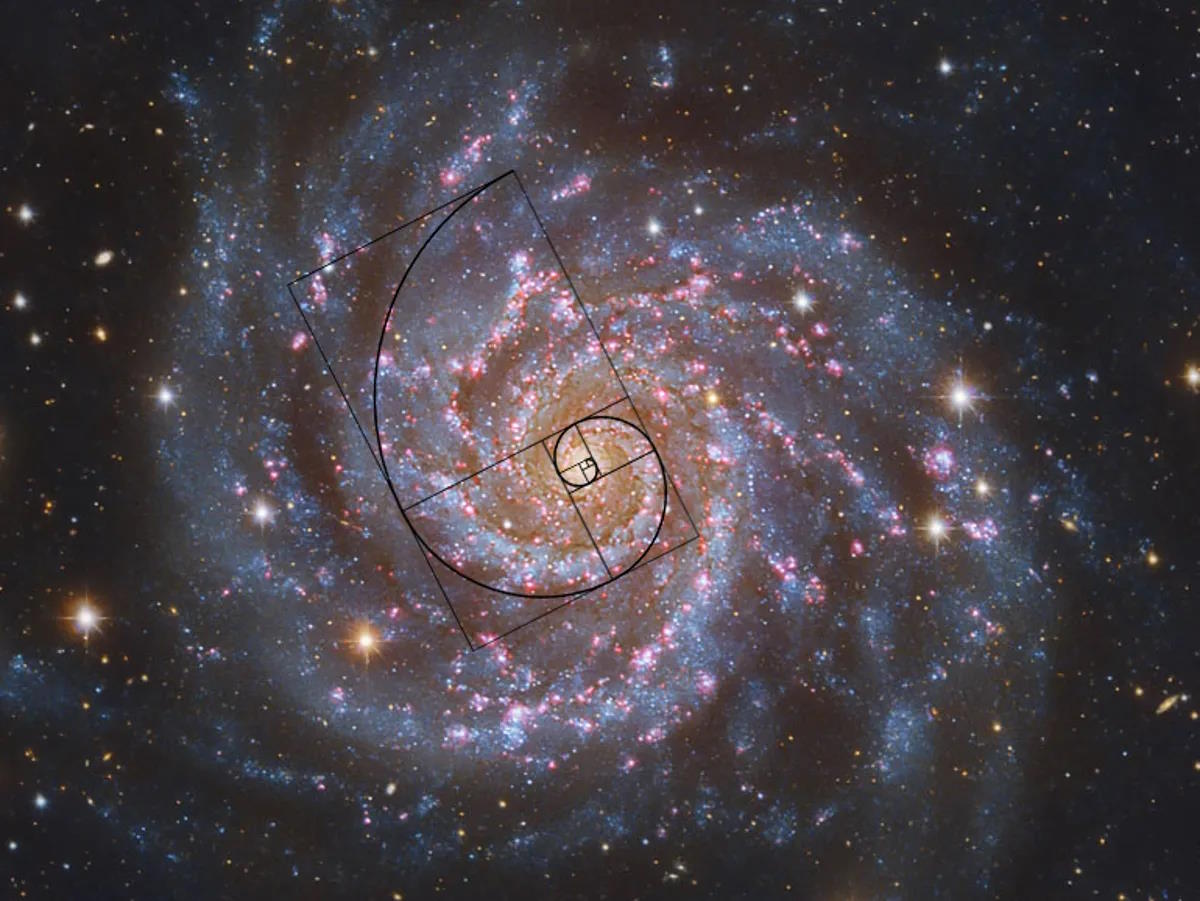

Indeed, simply looking at the “spiral” structures in galaxies might appear to be Fibonacci-like, but is that real, or just our minds making superfluous connections where only an apparent link exists?

Galactic and other physical spirals

When it comes to spirals that naturally occur in the purely physical sciences, “spiral galaxies” are undoubtedly the most famous among them. Somewhere just over half of all known large, nearby, massive galaxies have spiral shapes and structures within them, but when we examine them mathematically, it turns out that there are very few of them that exhibit a Fibonacci-like pattern.

Importantly, a Fibonacci-like pattern is what we call “self-similar,” where if you zoom out, and look at it on larger scales, that same structural pattern repeats itself when you zoom in to smaller scales. The spiral structures seen in galaxies don’t do that in two separate ways, as:

- the interiors of spiral galaxies rarely spiral in all the way to the center, but rather terminate in an asymmetric galactic bulge or bar,

- and the exteriors of these galaxies — in which the stars, gas, and dust are largely confined to a disk — are better approximated by the curve of a circle than by any “spiraling-out” structure.

Remember that the spiral arms within a galaxy are caused by density waves, and by the galaxy “winding up” over time. There are a few notable features that exist in some spiral galaxies that exhibit a Fibonacci-like pattern over those in-between regions, but this is not the norm.

The few spirals that do show that Fibonacci-like pattern are a part of a class of spirals known as Grand Design Spiral Galaxies, and these represent only about 1-in-10 spiral galaxies, as opposed to the most common types with multi-arm spirals (including the Milky Way) and the second most common type with subtle, many-laned spiral structure known as flocculent spiral galaxies. These “grand design” spirals are almost exclusively galaxies that have recently undergone or are currently undergoing a gravitational interaction with a nearby companion galaxy, and it’s only that external gravitational influence that pulls the outermost arms and features into shapes that are more consistent with ratios found within the Fibonacci sequence.

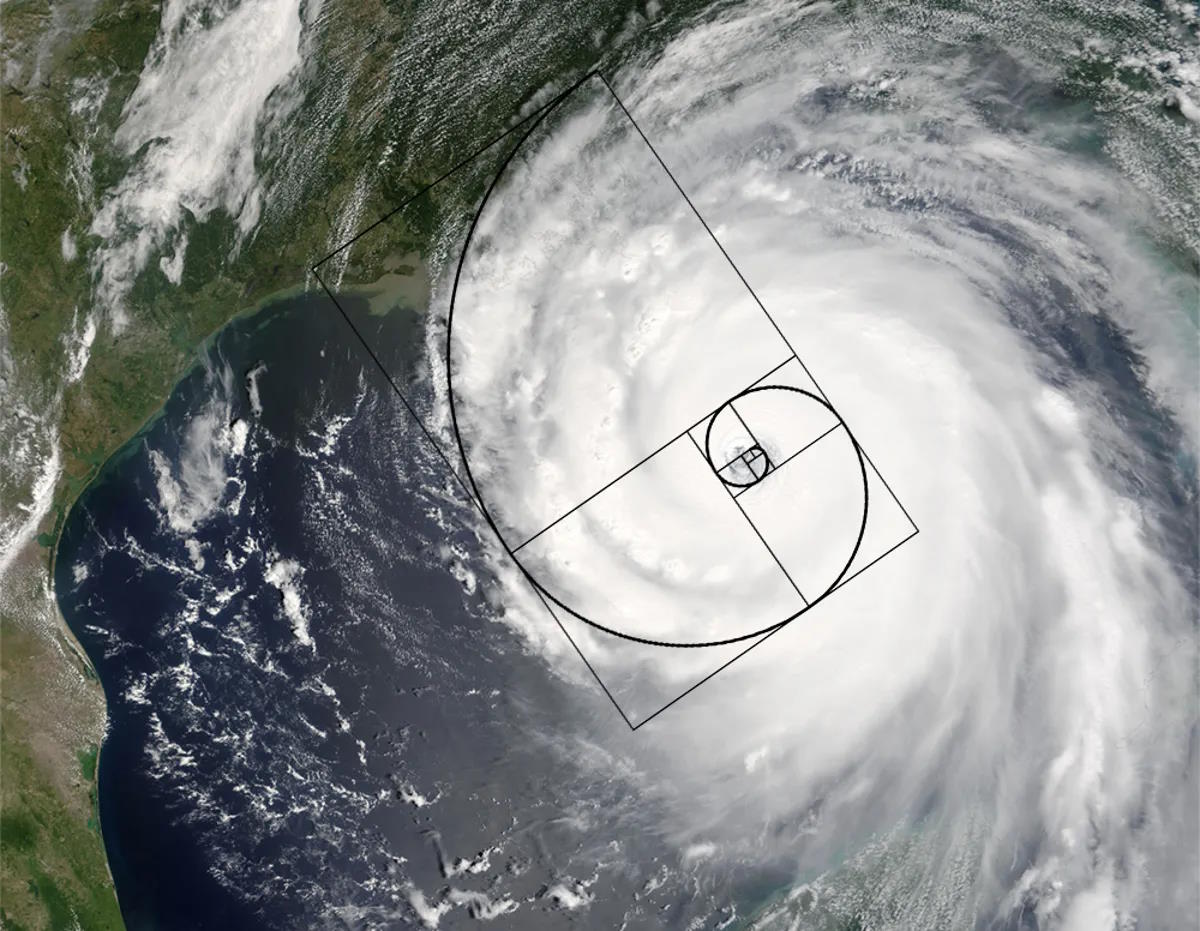

While there are many spiral shapes that occur from purely physical, non-biological processes in nature — from whirlpools and vortices that form in bodies of water to the aerial shapes of hurricane clouds and clear lanes — none of these spirals are Fibonacci-like when it comes to the actual mathematical details of their structures on a sustained basis. You may be able to take a “snapshot” where one or more of the features exhibits ratios that are consistent with the ratios found in the Fibonacci sequence for a particular moment, but those structures don’t endure and persist. The Fibonacci-like patterns seen in spiral galaxies are inventions of our eyes, rather than a physical truth of the Universe.

Biological Fibonacci spirals

However, the Fibonacci-like patterns and ratios found in many biological organisms, including in plants, truly are related to the Fibonacci sequence: both in a mathematically rigorous fashion and also for an evolutionary reason that makes perfect sense. Let’s tackle the biological properties first, and return to the mathematics.

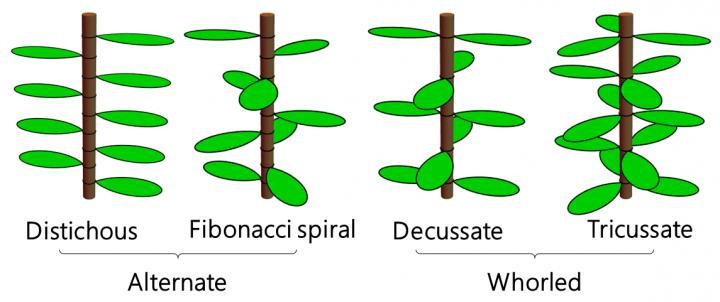

Biologically, let’s imagine you’re a plant: a primitive plant at that. You have the ability to generate your own energy from sunlight, soil nutrients, water, and carbon dioxide, and make sugars (stored energy) through the process of photosynthesis that takes place in your leaves. When you sprout from a seed, you have to put leaves out, and somewhere — buried in your genetic code — will be a piece of information telling you what angle to put your “next leaf” out at relative to the previous leaf.

You can go the simplistic route that a plant like a clover takes, and simply put out three leaves at an angle of 120° to one another: making a triangular pattern. The problem with that route is that it’s efficient, but not scalable. We don’t have giant clover trees because you can’t “scale” that up: when you put out three leaves at 120° angles relative to each other, there’s no place to put a “next” leaf that isn’t either very efficiently blocked by the prior leaves, or won’t be an efficient blocker for the prior leaves collecting sunlight.

But what if you wanted to encode the most efficient way to put your “next leaf” out, based on wherever you put the previous leaf? Sure, for a total of three leaves, 120° is mathematically perfect, but for an arbitrary number of leaves, it won’t do you any good. Imagine that you’re a plant, growing upward, and you’ve just put out your first leaf. As you grow upward and you go to put out your second leaf, what angle should it go out at so that not only the first and second leaves, but also the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and so on, will all get the maximum amount of sunlight when they’re all in place?

The answer is that, for each leaf, the next leaf should be put out right around 61.8% of a complete circle away from the prior leaf. For a circle with 360° in it, that corresponds to an angle of 222.5°, and the exact number that corresponds to is what mathematicians define as –ψ, which equals (√5 – 1)/2, or approximately 0.61803398875. The positive version of that, (√5 + 1)/2, is known as φ, or the golden ratio, and is 1/(-ψ), which happens to equal 1 + (-ψ) as well: the ratio between each Fibonacci number and its predecessor. If you keep putting out leaves at that key angle, 222.5°, relative to the prior leaf, you’ll wind up with your leaf patterns forming a Fibonacci spiral. That same mathematical property, encoded into pineapples, pinecones, and more, explains why biological organisms often display numbers found in the Fibonacci sequence.

The mathematics of Fibonacci

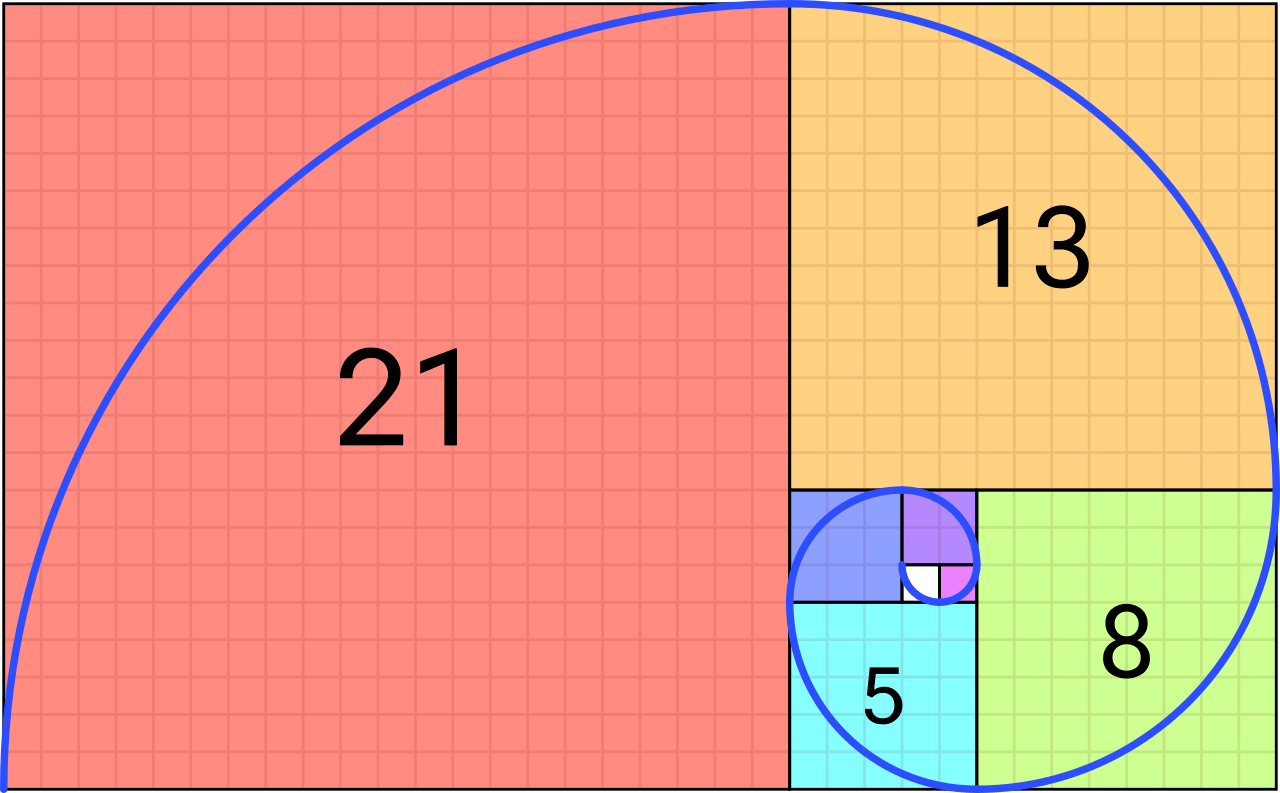

But the big question isn’t “why the Fibonacci sequence is found in nature,” but rather, “what is it that determines the Fibonacci sequence” in the first place? It’s pretty easy to calculate the Fibonacci numbers; all you have to do is start with the first two numbers: “0” and “1” to begin, and then make the next term out of the prior two terms combined. The first few terms of the Fibonacci sequence are then:

- 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181, 6765, etc.,

where you can verify that each successive term can be arrived at by looking at the two terms prior.

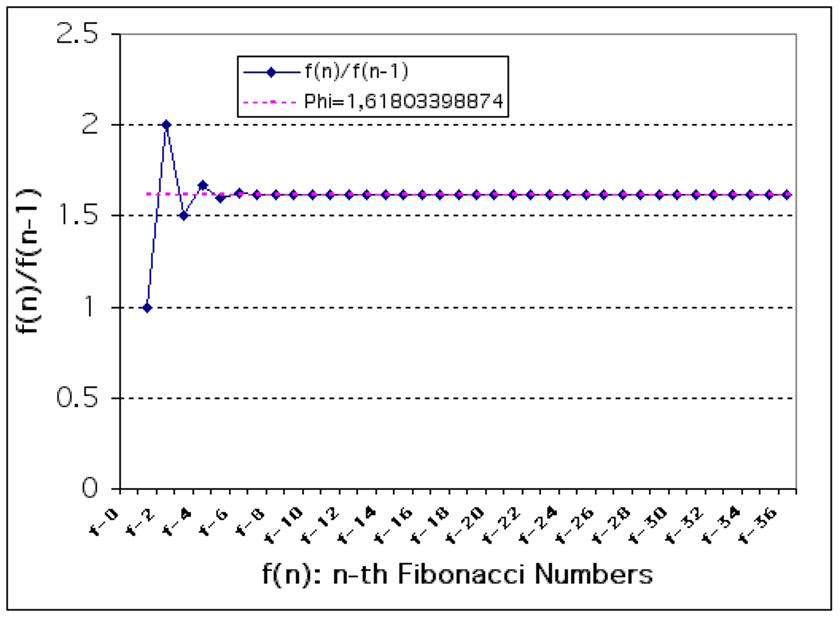

Now, let’s look at the ratios of any two successive terms relative to one another, and figure out what the ratio of the “next” term is to the “prior” term, starting with the two “1s” in the sequence (so that we don’t wind up dividing by zero).

- 1 ÷ 1 = 1.0,

- 2 ÷ 1 = 2.0,

- 3 ÷ 2 = 1.5,

- 5 ÷ 3 = 1.66666…,

- 8 ÷ 5 = 1.6,

- 13 ÷ 8 = 1.625,

- 21 ÷ 13 = 1.61538462…,

- 34 ÷ 21 = 1.61904762…,

and so on. As you can see, terms oscillate between being slightly less than φ, the golden ratio, and slightly greater than φ, but approach it, both from above and below, as we go to greater and greater terms.

By the time you get up to very large terms, it’s easy to see how close you get to the golden ratio. If we were to look at the final three numbers written above — 2584, 4181, and 6765 — you can see that the ratios:

- 4181 ÷ 2584 = 1.61803405573, and

- 6765 ÷ 4181 = 1.61803396317,

very quickly and very closely approach the golden ratio, φ, itself. If we go up just a few more numbers, to 10946, 17711, 28657, 46368, and then 75025 (the last Fibonacci number under 100,000), we find that the ratio 75025 ÷ 46368 = 1.61803398896: an estimate for the golden ratio that only differs once you expand out to the 11th significant digit.

It turns out there’s nothing special about the starting point of the Fibonacci sequence, either. You can start with any two non-negative numbers that you like where at least one of them is non-zero: they need not be “0” and “1,” they need not be whole numbers, they need not be close together. All you need to do is follow the same formula, where you take the first two numbers and add them together to make the next (third) number, and then add that number with the previous to make the next subsequent number, and so on. No matter which numbers you start with, the ratio of any two successive numbers will quickly approach φ, the golden ratio.

A generating Fibonacci fraction

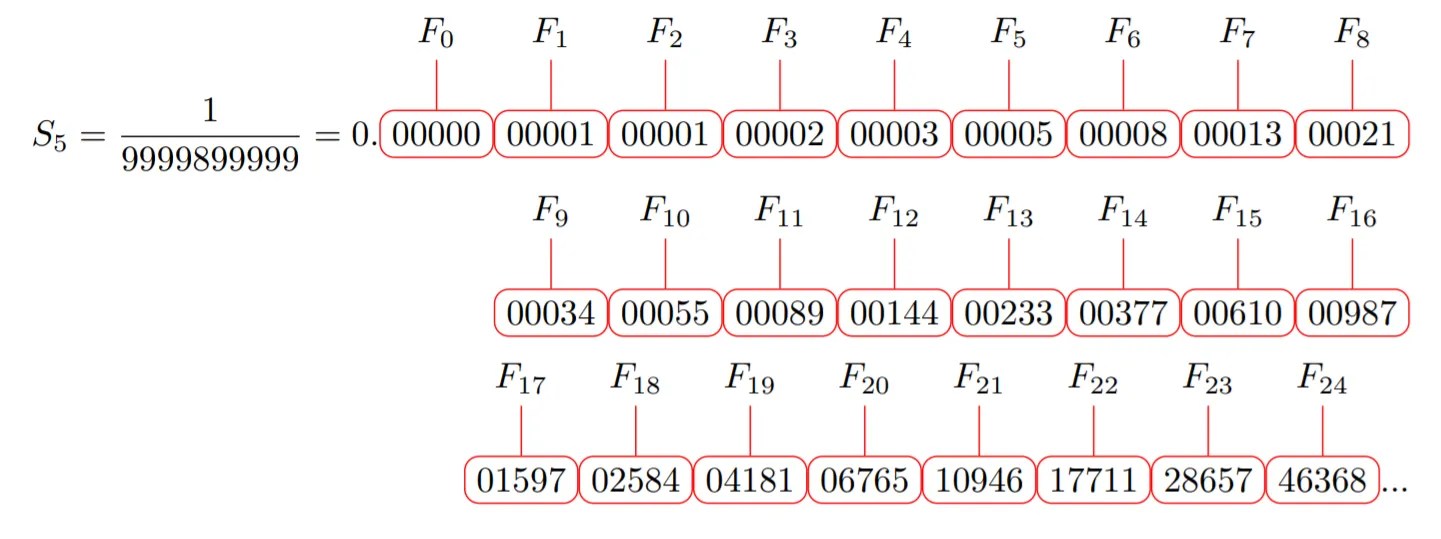

It’s enough to make one wonder: is there a way to simply generate any-and-all of the Fibonacci numbers without having to sum up each of the previous terms to get there? It turns out there is, and it’s an incredible mathematical curiosity. The key, believe it or not, is the 11th number in the Fibonacci sequence: 89.

What’s so special about the number 89? On the surface, not so much. The two ratios that it’s a part of, 89 ÷ 55 and 144 ÷ 89, don’t appear special: they come out to 1.6181818… and 1.6179775…, respectively. But if you instead take a very different ratio, of the number 1 to the number 89, you notice something a little bit odd. If you write it out as an expanded decimal, you’ll find the first few numbers of the Fibonacci sequence just appear, and appear in order.

- 1/89 = 0.011235955…,

in which we can see the first few recognizable numbers easily: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, and 5. You might look at the “9” and think it goes awry there, but remember that the next two numbers are 8 and 13, and so we involve some sort of “carrying over” that can transform what we’d hope to be an “8” into a “9” if we do our addition properly. There’s a clever trick we can then leverage to test for the Fibonacci pattern a little more expansively.

Instead of using the number 89, let’s remember we’re in base 10, so let’s help ourselves out by appending a “9” on either side of that number 89, to instead create the fraction 1/9899. When we expand that out — to more digits this time — here’s what we find as its decimal expansion:

- 1/9899 = 0.0001010203050813213455…,

and suddenly we see many more Fibonacci numbers emerging. What if we tried adding a few more 9s to either side? Say, 1/99989999? Now the decimal expansion becomes:

- 1/99989999 = 0.00000001000100020003000500080013002100340055008901440233037706100987159725844181…,

and we can see that more and more terms are emerging before we run into “carrying” errors. Add more 9s on either side of your denominator, and you’ve got a formula for generating the Fibonacci numbers, in order, appearing in your fraction, as far as you dare to expand it out. You can simply read the numbers off, and by adding as many 9s as you like, in equal numbers, on either side of “89” in the denominator, a decimal expansion will give you all the Fibonacci numbers, guaranteed, with fewer digits in it than the number of “9s” you put on either side of the fraction’s denominator.

But it all comes back to “89” for a profound reason. Imagine that we added up the terms in the Fibonacci sequence by dividing each term by 10(n+1), where n is the number of that term. In other words, that means our additive sequence looks like:

- 0.0 + 0.01 + 0.001 + 0.0002 + 0.00003 + 0.000005 + 0.0000008 + 0.00000013 + 0.000000021 + 0.0000000034 + 0.00000000055 + 0.000000000089 + 0.0000000000144 + ….,

and so on. Now, let’s do a little math trick: we’ll multiply that sequence by 10, and then subtract the original sequence from it (giving us nine times the original sequence). That looks like this (ignoring the first term, which equals zero):

- 0.1 + 0.01 + 0.002 + 0.0003 + 0.00005 + 0.000008 + 0.0000013 + 0.00000021 + 0.000000034 + 0.0000000055 + 0.00000000089 + 0.000000000144 + … – (0.01 + 0.001 + 0.0002 + 0.00003 + 0.000005 + 0.0000008 + 0.00000013 + 0.000000021 + 0.0000000034 + 0.00000000055 + 0.000000000089 + 0.0000000000144 + …),

which, if we take the first term separate and then group each subsequent term together, gives us:

- 0.1 + (0 + 0.001 + 0.0001 + 0.00002 + 0.000003 + 0.0000005 + 0.00000008 + 0.000000013 + …),

which tells us that nine times the original sequence equals 0.1 + one-tenth of the original sequence!

Or, in other words, that the original sequence, i.e., the sum of the numbers in the Fibonacci sequence sorted by decimal places, equals 0.1/8.9, or 1/89. And that’s why the Fibonacci sequence isn’t inherent to nature, but rather, to pure mathematics instead. It appears in nature because the golden ratio has a biological utility, but wherever it appears in the physical sciences, including in some spiral galaxies, it’s only by pure coincidence!

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!