Why do Supermoons always come in a row?

October had one, November will have one and December will have one, too. What’s the science of Supermoons?

“The supermoon is a 16-inch pizza compared with a 15-inch pizza. It’s a slightly bigger moon; I ain’t using the adjective ‘supermoon.’”

–Neil deGrasse Tyson

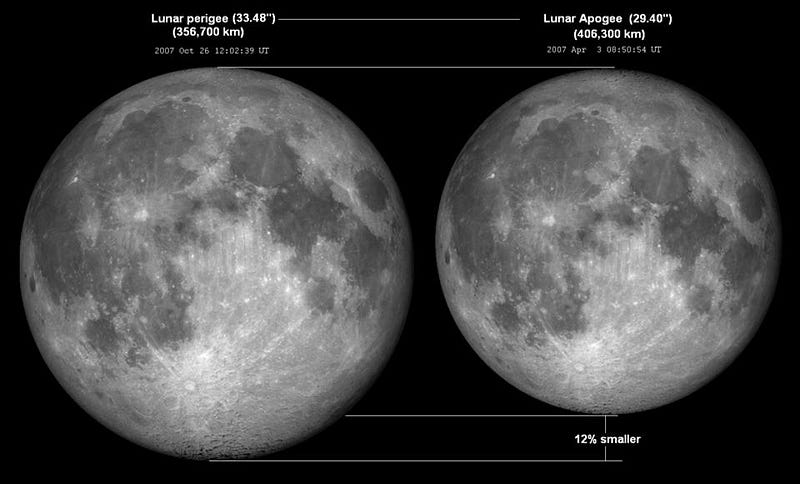

Many of us will look out at a full Moon and think to ourselves, “wow, the Moon sure does look big tonight.” If you’re a very astute skywatcher, you might actually notice that the size of the full Moon varies throughout the year: the largest full Moons are 7% larger and 15% brighter than average, while the smallest full Moons are smaller and fainter by about the same amount. The difference between the largest ones, known as Super Moons, and the smallest, known as Micro Moons, becomes readily apparent if you view them side-by-side in photos: a 14% size difference. But what’s the science behind them, and why they usually come three-in-a-row?

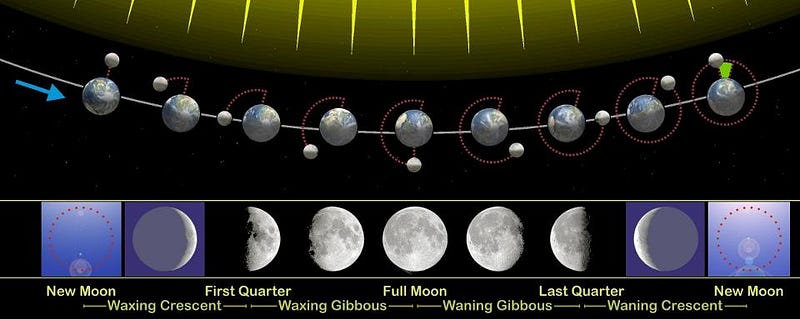

The first key lies in the Moon’s orbit around the Earth. While we think of the motions of planets and moons in our Solar System as being near-perfect circles, the truth is that they’re actually ellipses, with some orbits having quite a significant deviation from true circularity. In the case of our Moon, the differences are pretty severe: the Moon’s closest approach (perigee) to Earth takes it to within 356,375 km of our planet, while at its most distant (apogee), it’s 406,720 km away. Most perigees are around 1% farther than this and most apogees around 1% closer, but these are the orbital extremes. If you watched the Moon’s angular size as viewed from Earth over the course of a month, you’d see these orbital changes in action.

But each Moon cycle would appear different from the previous one. Not every full Moon coincides with perigee, and not every new Moon coincides with apogee. If you picture the Moon’s orbit as an ellipse around the Earth, you then need to consider that the Earth — and therefore the Moon’s ellipse — revolves around the Sun as well. What does the Moon’s orbit do in this situation? The ellipse stays in approximately the same fixed orientation as the Earth revolves around the Sun, actually lagging behind a little bit. While the Earth takes a little over 365 days to return to its original starting point as it orbits the Sun, the time it takes the Moon’s perigee to return to the same starting point with respect to the Sun is 411 days, due to the Sun’s tidal influence on the Earth-Moon system.

This means the Moon appears to go through a full cycle, where full Moons appear largest, smallest and rise to largest again, every 14 lunar months. A “Super Moon” or “Supermoon” is defined as any full Moon that occurs close enough to perigee so that its distance from Earth in its maximally full phase is 361,524 km away or less: 90% or better of the Moon’s closest approach to Earth. If you took a look at a full lunar cycle and examined the Moon’s perigee that occurred closest to a full Moon, you’d find that it met the Supermoon criteria 100% of the time. This year, that date occurs on Nov. 14, which will be the largest — or most “Super” — full Moon of the year.

But the full Moons on either side of that will also be quite “Super” as well! This year, the October and December full Moons are also Supermoons, and in fact on most occasions we’ll see three Supermoons in a row from our perspective on Earth. On rare occasion, the lunar orbits, perigees and the Sun’s position will conspire to give either two or four consecutive full Moons that meet the Supermoon criteria, but three in a row is almost always what we get. Still, only one full Moon will be the “most Super” in any 411 day period, and that’s what November’s will be. Yet the previous one, on Sept. 27, 2015, held a very special treat.

It coincided with a total lunar eclipse, the first time since 1982 that had occurred! If you’re interested in the next “most Super Supermoon Lunar Eclipse,” you’ll have to wait until 2033, where the biggest, brightest full Moon of the year will plunge into Earth’s shadow, bringing a beautiful red glow to the night sky.

In the meantime, enjoy the views that three Supermoons in a row will bring to end the year, with the full knowledge that even if clouds, foul weather or even falling asleep unexpectedly early keep you from missing the most “Super” full Moon of the year, the very next one will always be almost as brilliant!

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!