Why science matters more than ever in Trump’s America

It may be the only way to save the USA — and the world — from alternative facts.

“If your experiment needs statistics, you ought to have done a better experiment.” –Ernest Rutherford

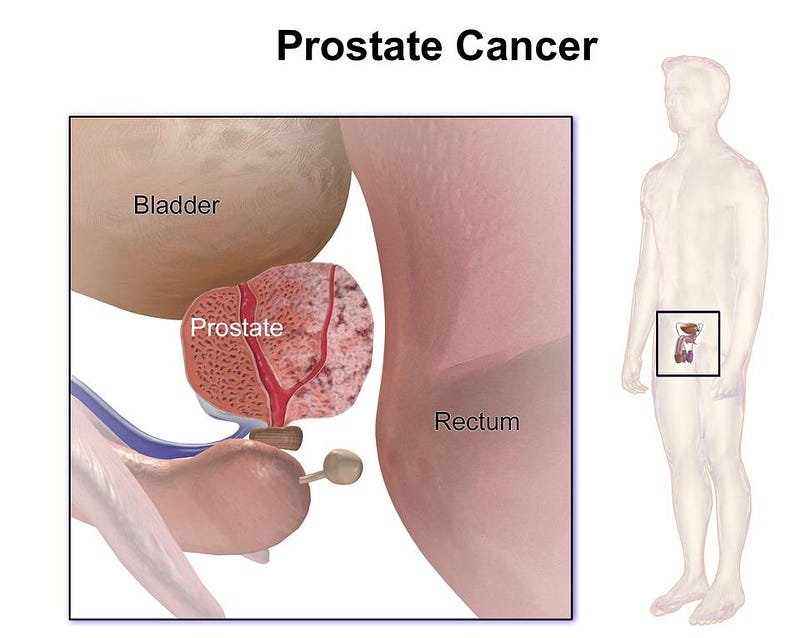

There are big problems that come up in our lives, affecting our hopes and dreams for ourselves, our family, and even our very lives. How are you going to pay for your child’s college education? Is it a better decision to buy a new car, a used car or to fix your current car one more time? When your knee starts hurting chronically, affecting what you choose to do in your daily life, should you have the knee replacement surgery? And if your doctor diagnoses you with prostate cancer, should you have the prostate removed, should you have radiotherapy or should you simply have it actively monitored?

These are hard questions, not so different from the ones many of us face in our lives. But the way we approach them, if we want the best outcomes, is the same way we’d want our government to approach the problems facing our nation today. It’s also, at a fundamental level, the same way scientists approach any problem they face. It’s a way each of us not only applies science to our everyday lives, but should demand that those making decisions on our behalf think scientifically as well.

Each of the personal or family problems we might face appears to be unique, but there are similarities to how we’d approach them.

- For your child’s education, you’d start saving money early, investing it for the future, and later on encouraging your child to apply for student aid, to research and apply for grants and scholarships, work/study and to take out loans as necessary. You’d want them to go to the school of their choice, to follow their educational dreams, and to help them shoulder as much of the financial burden as you can.

- For your car, you’d have to do the math: how much is your current car worth, versus how much does it cost to fix, versus how much life you’re likely to get out of it. And then you’d have to compare that to how much a new/used car would cost versus the lifespan and enjoyment and cost-of-upkeep you’re likely to have to spend on that.

- For the knee surgery, you’ll have to evaluate the cause of your pain, whether there’s bone-on-bone contact, how old you are and how long the replacement is likely to last, and whether a future re-replacement is likely to be a viable option. You’ll also have to look at the success rates for the surgery for patients like you, and evaluate what route is likely to give you the best outcome.

- And finally, for prostate cancer, you’ll have to weigh a whole slew of factors about your quality of life with and without your prostate, whether the cancer is likely to kill you or not, what the outcomes of the different courses of treatment are and what the risks are of having (or not having) various surgeries or treatments.

In all of these cases, there are a slew of commonalities.

To start, you’re likely to have a gut instinct about all of these issues. Maybe you want to put aside all you possibly can and invest it into tech stocks for your child’s education. Maybe you want to fix your current car, thinking that there’s plenty more life in it. Maybe you want your knee replaced, just wanting the pain to end. And maybe you want to go the active monitoring route with your prostate, as the risks of losing urinary control and sexual function are too high a cost to pay.

But going with your gut isn’t always going to be the best approach, and you know that. Even if you have good instincts, you know that you’re better off gathering as much information as you can. That means doing all the research you can into learning as much as you can about all the possible options, outcomes, and how they relate to your specific situation. It means learning the pros and cons of all the options available to you; it means carefully weighing the best evidence you can accumulate. In short, it means doing your homework to the best of your abilities, and making your decision — that sometimes runs counter to your gut — based on the information that you find.

Despite all that you can learn and all the information you can collect on your own, you’ll never have as much expertise as the people who’ve devoted their entire lives to this. A financial planner will offer you options and advice that you most likely wouldn’t have come up with on your own, with a slew of research and reasoning to back up their recommendations. A reliable, scrupulous auto mechanic can tell you whether your car is worth fixing or not in detail, while an impartial third-party expert reviewer can tell you about the value of a new/used car. Medical professionals specializing in knee replacements can tell you about whether knee replacement surgery is recommended for you or not, as they’ve kept up with the latest research and are more aware of the nuances as they affect your particular case than you could ever be. And not only does the same thing go for prostate cancer, but the latest research may influence your doctor’s recommendation; what they would have recommended five years ago might not be the best recommendation today. Our knowledge base grows, and as it does, the best course of action may be different.

That’s why it’s so important to not listen to an authority without the requisite expertise, but to seek out an impartial, third-party with expert knowledge. That’s why it’s so important to not fall victim to the trap of motivated reasoning: the easiest way to fool ourselves. It’s all too easy to arrive at a position and convince ourselves it’s the right/best one. Sometimes, our gut instincts are enough to do so. Sometimes, we’ll do our information gathering and that will cement our positions in our minds. And sometimes, we’ll find the experts who solidify that position. But we have to be open to new information, to the possibility that we’ve gotten it all wrong, and consider the option that there might be a better way of doing things than we’ve figured out so far. It’s how a (scrupulous) scientist views the world, and it’s one of the most challenging ways of thinking, as it requires us to constantly be questioning our assumptions and our prior conclusions.

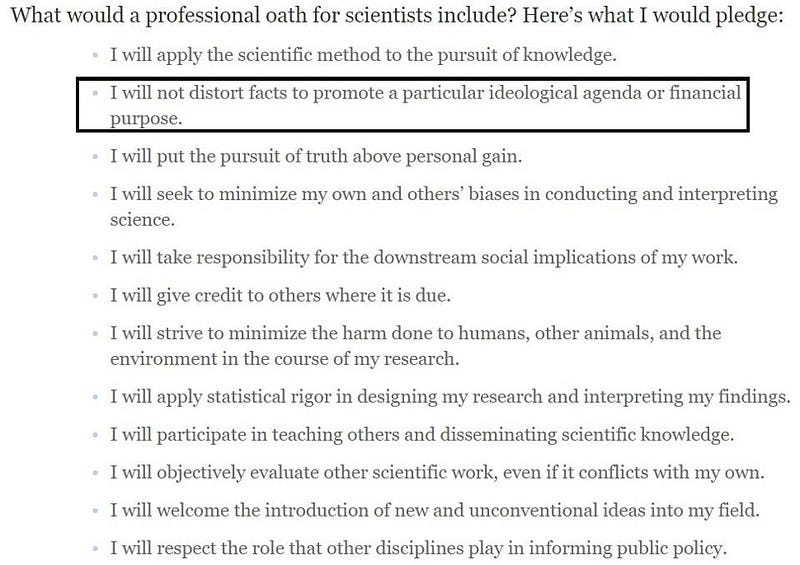

The trap we can all — scientists included — fall into is that we hate to change our minds. Once we’ve made a decision about what the best conclusion or course of action should be, we tend to lose our objectivity. We tend to go with the facts that support our previously-held positions, to interpret neutral facts as supporting what we already believe, and to discount or reject the facts that run counter to our opinions. It’s why so many have proposed that scientists take a scientific oath, similar to the Hippocratic oath that doctors take.

There are a lot of good points, but one stands out in particular as one that we can all apply to our lives.

I will not distort facts to promote a particular ideological agenda or financial purpose.

There are a number of pushes made recently to vilify and disempower scientists; to frame their expertise as mere opinion; to remove them from positions where they can share and make knowledge public. But it’s that very expert knowledge that we all need access to if we want to make the best decisions possible. In the fight for free speech and free information, it’s vital that we value the voices speaking the truths that they’re best qualified to speak about. And when those voices run counter to how we’re living, what decisions we’ve made or what we’re planning on doing next, that’s when it becomes most important to hear and consider that information. Even — nay, especially — when it’s inconvenient.

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!