Why you can’t see the Moon during a total solar eclipse

The new Moon is brighter than every star in the sky. But you’ll never see it during an eclipse.

“Even though the reason for taking the photographs was science, the result shows the enormous beauty of nature.” –Miloslav Druckmuller, eclipse photographer

The moments of totality during an eclipse are something rare and special for anyone who gets to experience it. They’re only possible when the Sun, Earth and Moon perfectly align at a moment when the Moon is close enough to block the entire Sun’s disk, from an Earth-bound observer’s perspective. As the shadow of the Moon falls on the Earth, the sky darkens, and stars, planets, and the Sun’s corona appear visible to human eyes during the day. Yet to those of you who’ve seen a thin crescent Moon before, one sight is missing: the face of the Moon itself, normally illuminated by Earthshine. To someone who’s viewed the Moon routinely, it may come as a baffling surprise.

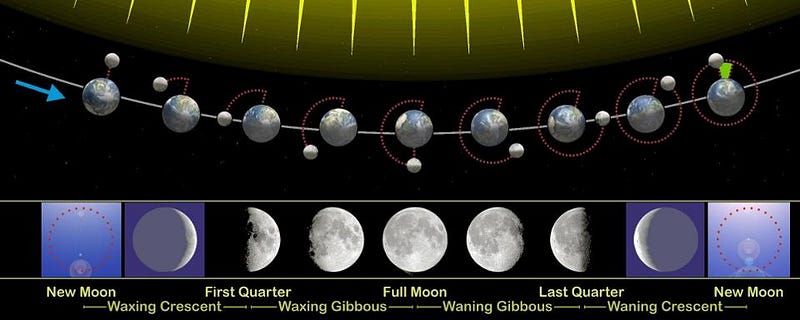

The Moon is very close to a perfect sphere in shape, and like all spheres (including Earth), precisely 50% of it is illuminated by the Sun at any given time. When the Moon is very closely aligned with the Sun, it appears in a “new” or “almost new” (crescent) phase, as the hemisphere that’s lit up mostly faces away from Earth. But you can still see the non-illuminated portion thanks to the phenomenon of Earthshine. Even when direct sunlight doesn’t fall on the Moon, light from the Earth does.

Imagine the Earth as though it were a mirror. It may be a fairly lousymirror, reflecting only about 30% of the incoming sunlight, but it’s also large enough that a significant portion of the sunlight reflected by the Earth winds up falling onto the Moon. If you stood on the surface of the Moon during its “new Moon” phase and looked towards the Earth, you’d see an object that appeared to be 1/10,000th the brightness of the Sun.

This light would be more than 40 times brighter than the full Moon appears from Earth. The light that the Earth reflects onto the Moon is so great that even during a perfectly new phase, even during a total solar eclipse, the Moon is still 150% brighter than Sirius, the brightest star in the entire night sky. At the maximal moment of a total solar eclipse, dozens (if not hundreds) of stars are visible to the naked eye, all of which are are fainter than the new Moon.

But despite all that you can see, the face of the new Moon isn’t visible to human eyes, even during a total eclipse. In fact, only if you take quite a long-exposure photograph with a camera can you see anything other than total blackness where the Moon resides in the sky. Yes, the light is really there, but your eyes are completely unable to perceive it, even when the sky gets so dark that objects hundreds of times fainter can be seen.

Why is that? The same reason you can’t see stars at night if they’re located too close to the full Moon: there’s something else that’s much brighter than the new Moon right by it. That’s the Sun’s corona! At temperatures of over 1,000,000 degrees, the corona is never visible when there isn’t an eclipse, due to the fact that the Sun itself is shining right next to it. But the Sun’s corona is approximately as intrinsically bright as the full Moon; if it weren’t located so close to the Sun itself, you’d be able to see it even during the day.

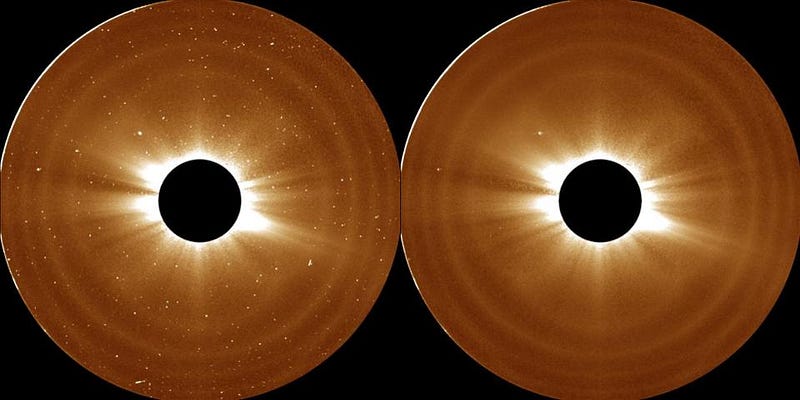

Astronomically, if you were to build a device that blocked out the disk of the Sun but not the corona beyond it, you can view that hot, outer atmosphere of the Sun during the day. Such a device is called a coronagraph, and astronomers have used them since the 1930s to view the solar corona. Without one, however, the brightness of the Sun overwhelms the brightness of the corona; it’s 400,000 times brighter and too close in proximity for you to view it. The situation is very analogous to what happens during totality between the corona and the new Moon.

Yes, there is Earthshine illuminating the face of the Moon. And yes, the new Moon’s face is 150% brighter than even the brightest star in the sky. But the corona is 10,000 times brighter than the new Moon, and is located only a quarter-of-a-degree from even the new Moon’s center. Your eyes may be sensitive enough to see something as bright as the new Moon, but not if something 10,000 times brighter is that close to it. If you stood 20 feet (6 meters) away from a 25 Watt light bulb, you couldn’t see a firefly light up one inch (2.5 cm) from the bulb, which is to take nothing away from the firefly.

Proximity matters, and in the case of the new Moon, it’s the solar corona that washes it out. The Moon is still illuminated, and that’s why a camera can pick up the details of its face. But the same corona that provides such spectacular sights is also what makes it so difficult to see anything around it. This applies not only to the full Moon, but to the stars closest to the Sun’s limb itself: essential for testing Einstein’s relativity!

There are some astronomical observations, even with a powerful telescope, that can only be made with the help of photography. To gather enough light to stand out against the brightness of other objects is something that goes beyond what human eyes can deliver. Thankfully, that technology is widespread today, and enables us to enjoy a whole slew of sights our eyes cannot deliver. It may be dark during the eclipse, but darkness, as we perceive it, is relative. Our Sun’s corona, during totality, will become the brightest thing in the sky, and is the reason the Moon, to human eyes, will be completely invisible.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.