Ask Ethan: Can you explain wide binaries and modified gravity?

- Stellar systems come bound together in many different ways: in singlet star systems, in multi-star systems, in clusters, and with stars at all distances, from contacting each other to barely being gravitationally bound.

- Over the past few years, multiple separate teams of researchers have put forth claims contending that this data supports modified gravity, refutes modified gravity, or supports one model of modified gravity over the others.

- In reality, the situation is much more complicated, as there is little agreement on how to interpret this data. However, the truth about modified gravity theories should be known by everyone.

For more than 50 years, there’s been a mystery about the Universe that the greatest minds in physics and astronomy have been unable to solve: the fact that, when we map out all of the known matter that we can see and apply the known laws of gravity, it doesn’t add up to match the Universe we observe. Somehow, there are additional gravitational effects that appear, and on a wide variety of scales.

- In the Solar System, the matter we observe explains the gravitational effects we see according to our standard theory of gravity.

- On the scales of a galaxy, either a new type of unseen matter or a modification of gravity is required.

- On the scales of galaxy clusters, either an additional, massive ingredient or a modification to the rules of gravity is needed.

- And on large, cosmic scales, again, some additional ingredient or some modification to gravity is required.

If we seek to add just one new ingredient, cold dark matter can take care of the present mismatch on all scales. If we seek a modification to gravity, the most common one considered is MOND, or MOdified Newtonian Dynamics, which can explain the first two but requires some sort of additional ingredient or extra modification for the last two. But that’s not the only way to try to modify gravity. Another is brought to our attention by reader George Hampton, who was curious about something he came across:

“You’ve probably seen the recent paper Wide Binaries and Modified Gravity by J W Moffat. It would be great if you wrote about this and explained it a bit. I took a look at it and the math is beyond my knowledge.”

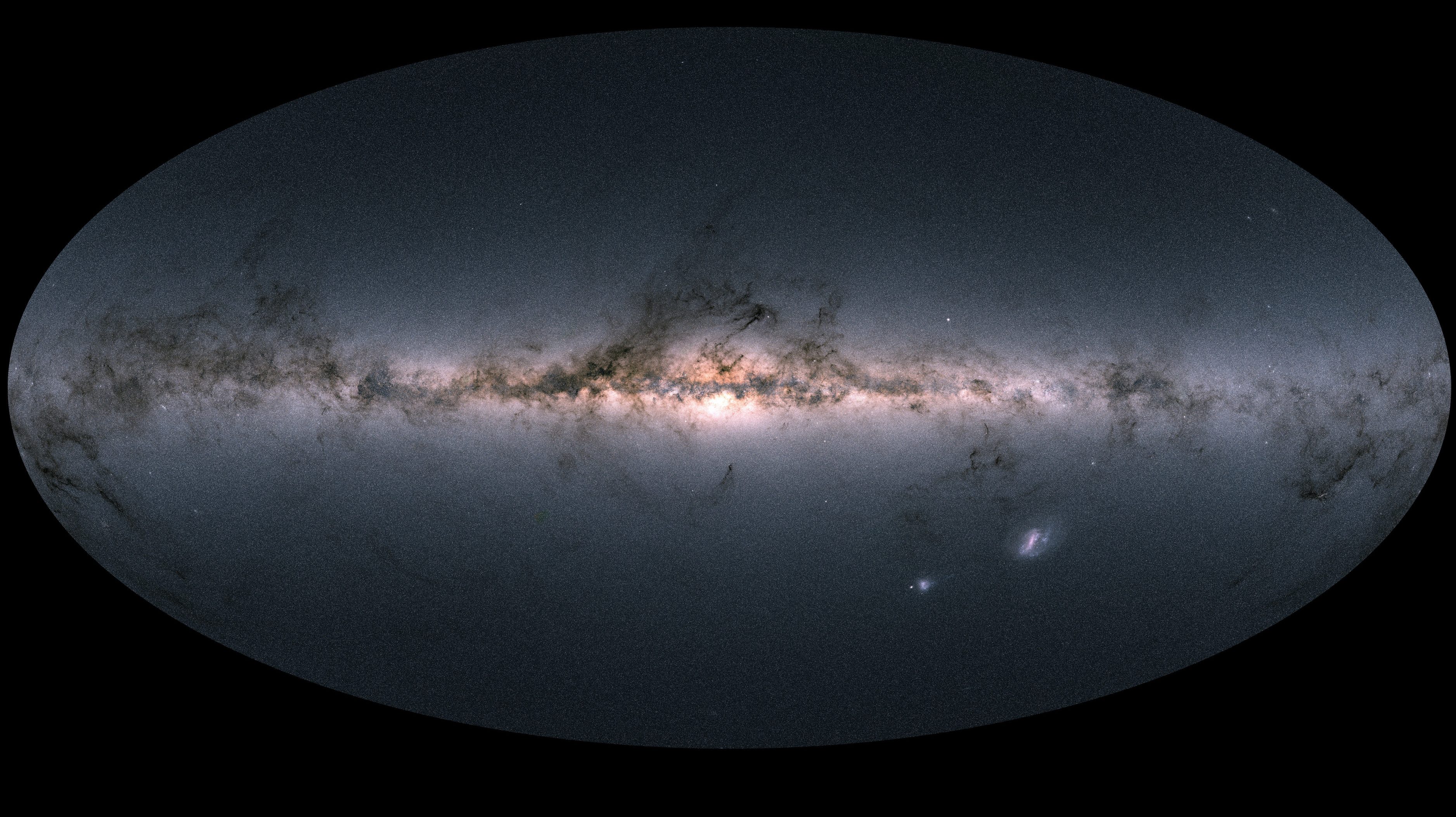

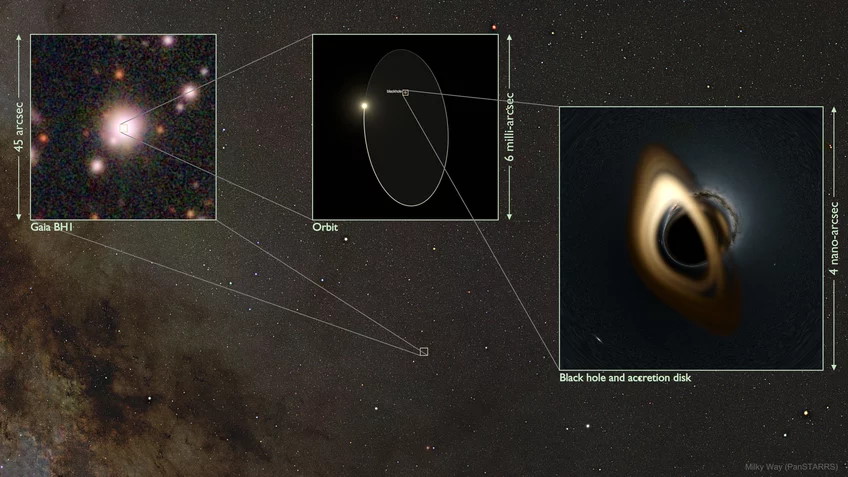

Moffat’s theory, known popularly as MOG (for MOdified Gravity), is very different from MOND, and wide binary stars are a newly popular testing ground for gravity thanks to the advent of data from the ESA’s Gaia mission. There’s a lot to unpack when asking about this, so let’s go one step at a time:

- first to explain Moffat’s MOG,

- then to talk about wide binaries,

- and then to look at the cumulative case for how we make sense of the Universe.

Here we go!

The theory of Modified Gravity

If we look our the standard theory of gravity — general relativity — we find that it’s built upon a very powerful idea: that the presence of all forms of matter-and-energy affect the structure of the underlying spacetime, and that the curvature and structure of the underlying spacetime dictates how all forms of matter-and-energy move through it. Effects like gravitational time dilation, the cosmological redshifting of light and gravitational waves, and the speed at which individual objects move within gravitationally bound structures are all determined by this theory of gravity, as well as many others. The speed of gravity, as well, must propagate at precisely the same speed as light, with no deviation allowed.

But if the normal, atom-based matter that we intimately know is all there is, general relativity can’t explain the gravitational behavior of a huge variety of structures in the Universe, including galaxies, galaxy clusters, and the clustering of objects on cosmological scales. The solution astrophysicists normally turn to is the theory of cold dark matter, which — if we add approximately 5 times as much dark matter as normal matter to the ingredients of the Universe — brings all scales back into agreement with observations. No other “fix” can do that: solve all of these puzzles on all of these scales with just one modification. But still, there are other lines of thinking worth pursuing.

In the early 1980s, the idea of MOND — MOdified Newtonian Dynamics — was put forth by Moti Milgrom. Rather than beginning with general relativity and modifying that, MOND began from Newtonian gravity and noted that, if when accelerations got very small, there were a deviation from Newton’s F = ma, where a was replaced by a mathematical function that depended on both the expected Newtonian acceleration and also a fixed acceleration scale, a0, that only contributed importantly at very small accelerations (where |a| < a0). That one modification leaves gravity consistent at Solar System scales, but then transitions to explain galaxy scale behavior, and arguably does it better than cold dark matter theories do.

The problem with MOND, however, is that it then requires either:

- a different, additional set of modifications to the law of gravity,

- or a new type of ingredient that’s indistinguishable from cold dark matter,

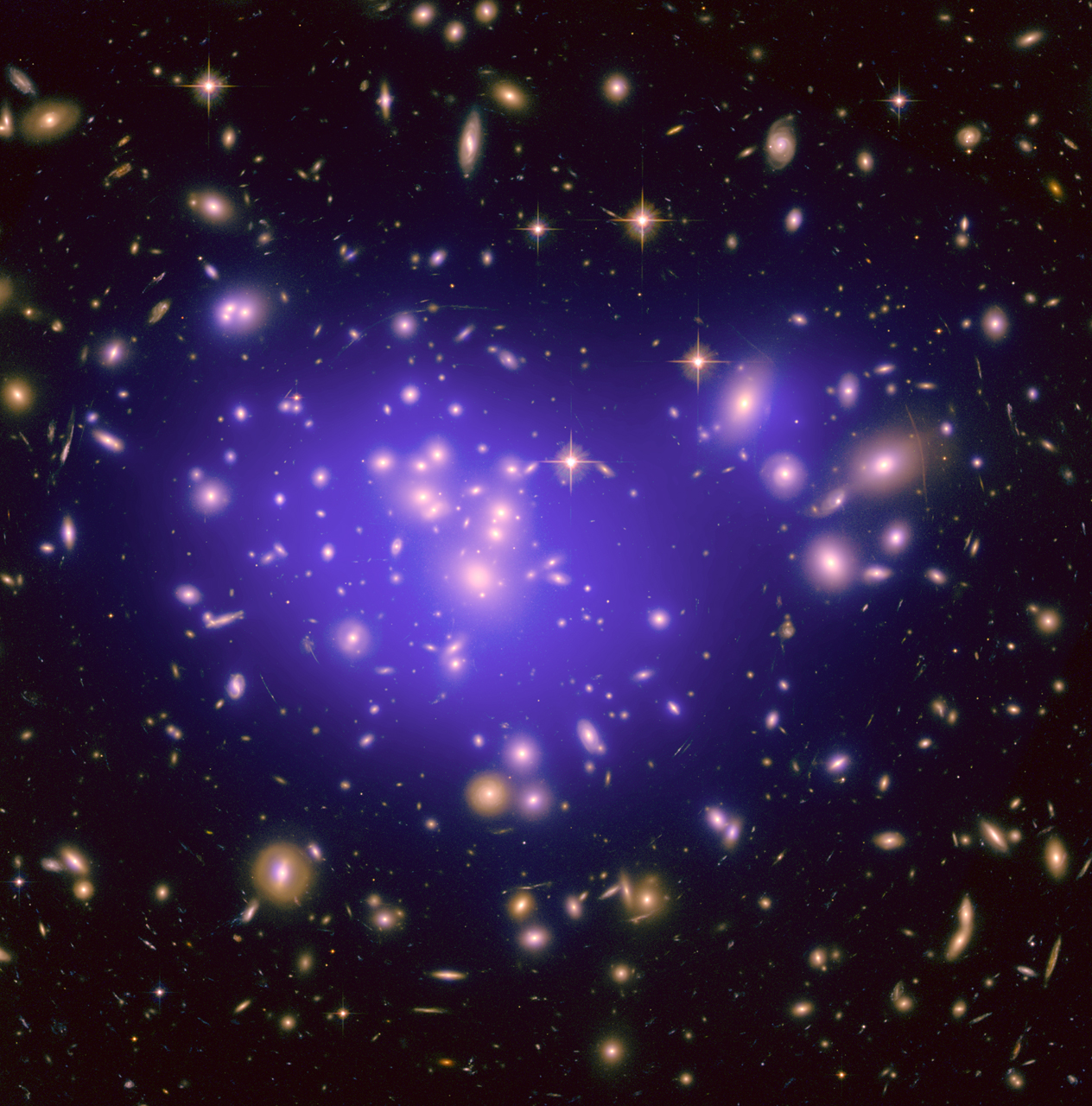

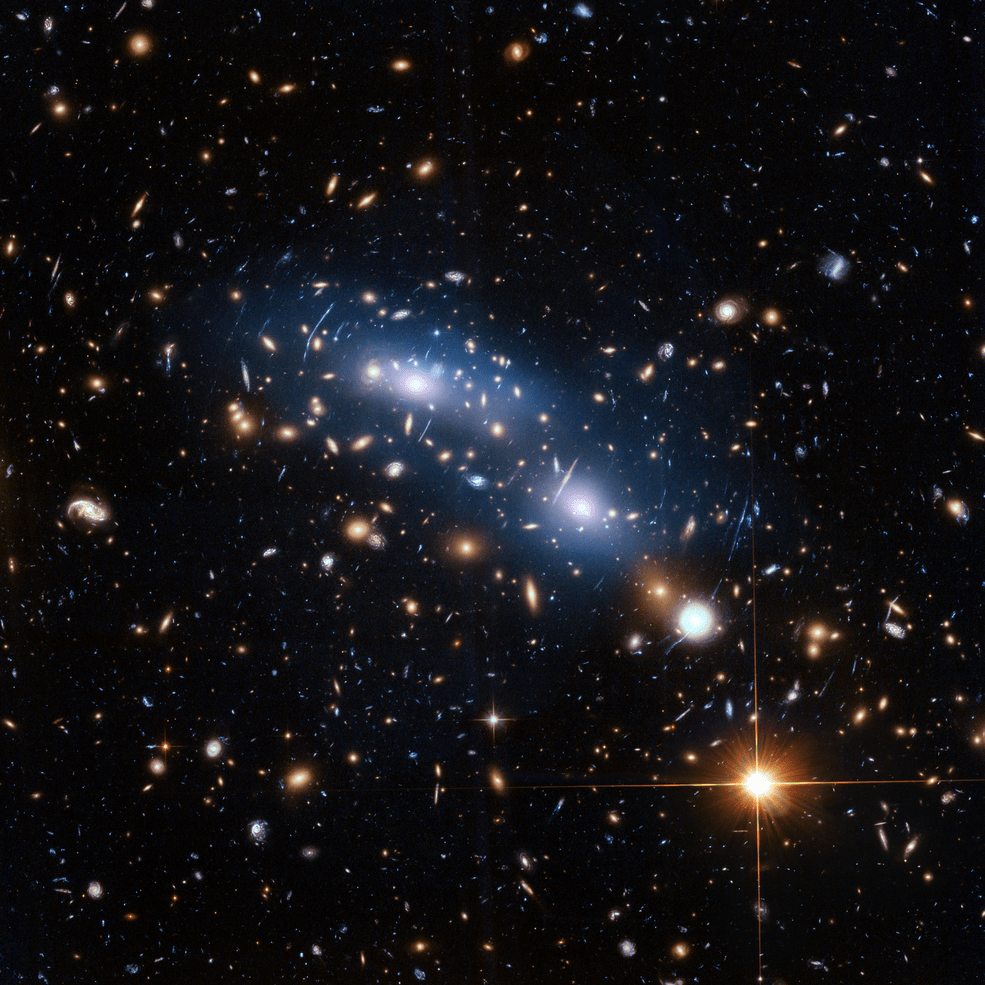

to explain behaviors of galaxy clusters and the properties of the Universe on cosmological scales. Furthermore, if you choose the first option (an additional set of modifications to gravity), you need yet another modification to either the law of gravity or the ingredients in your Universe to explain what we observe when two galaxy clusters collide. You see, when clusters collide, most of the normal matter is present in the form of non-luminous material — gas, dust, and plasma among them — that collides and heats up, whereas the individual stars and galaxies simply pass right through one another. Even though the majority of the normal matter is then in the center of where the clusters have collided, the majority of the gravitational effects observed is where the stars and galaxies have passed through each other: separate from the normal matter itself.

Relativistic extensions of MOND face extreme pressures from astrophysical systems such as these. However, MOND is not the only way one can attempt to modify gravity, and MOND’s modifications are not the only alternative to dark matter. Back around 30 years ago, theoretical physicist John Moffat, who was already well-known for speculative alternative ideas in theoretical physics such as a variable speed-of-light cosmology and non-local quantum field theories, proposed a modification to Einstein’s gravity that would go beyond the symmetric rank-2 tensor (the metric tensor) that is the hallmark of general relativity to add in additional non-symmetric terms: terms that were absent in Einstein’s gravity, but which could lead to additional physical effects.

Then, about 20 years ago, Moffat reached the point where he could put forth a MOdified Gravity (MOG) theory that incorporated both scalar and vector terms (both absent in general relativity) that did, in fact, account for the observed rotation curves of galaxies. In subsequent papers, Moffat showed that his theory can also explain:

- the mass profiles of galaxy clusters,

- post-collisional clusters such as the Bullet Cluster,

- and a variety of cosmological-scale observations (although that paper has been through seven revisions over 5 years, and has still, to date, never been published in a journal),

which makes it an interesting alternative idea worth considering. In the most recent paper he’s put out, Moffat also argues that his MOG theory, in contrast to MOND, agrees with the observations of wide binaries, just as standard general relativity does. So let’s look at that claim next.

Wide binaries and gravity in astrophysics

Whenever you have stars that are bound together into the same stellar system, you can predict the orbital speed of one star around the other simply by measuring how far apart the two stars are from each other. The law of gravity is simple and straightforward, and just as Kepler’s, Newtons, and Einstein’s laws apply to the motion of any two gravitational objects bound together, two stars are just another example of those types of massive objects.

- When stars are in tight orbits with one another, the velocities of the stars relative to each other is large, and the accelerations are also large.

- When stars are in orbits with greater separations, they orbit one another more slowly, are more loosely gravitationally bound, and experience lesser accelerations.

- And when stars have extremely great separations — which are the systems we typically identify as wide binaries — they orbit one another at extremely slow speeds (less than 1 km/s), are easily unbound by gravitational interactions with other objects in the interstellar medium, and experience tiny gravitational accelerations: often tinier than the critical (a0) scale in MOND.

The big idea is that, with the advent of the ESA’s Gaia satellite, we now have precise three-dimensional data about the positions and motions of literally more than a billion stars (and star systems) within our galaxy, over the baseline of a few years, and we can accurately track the orbits and motions of more stars than ever before.

So can we then use that data to determine if, at large enough separation distances, there really is a deviation from the expected Keplerian/Newtonian/Einsteinian motion that our standard theory of gravity predicts, and if there is, that deviation instead agrees with the alternative predictions of MOND: the MOdified Newtonian Dynamics idea that is the favorite darling among the “modified gravity” crowd. Moffat’s scalar-vector-tensor theory, MOG, interestingly deviates from MOND, and instead predicts an agreement with the more standard Kepler/Newton/Einstein prediction of standard gravity for these observations, and that’s the impetus for this new paper.

However, there’s an enormous issue with this approach. Yes, in theory, you can use high-quality position-and-velocity data to infer the orbital data about any type of binary system, and that with data over a long-enough period of time, you can infer the orbits of even the widest of binary systems. But in practice, the amount of data you need — i.e., the duration of time you need as a baseline for accurate orbital determinations — is dependent on the amount of time it takes to make a complete orbit. In our own Solar System, for instance, we can determine the orbital motions of Kuiper belt objects, at around 50 Astronomical Units (where one Astronomical Unit is the Earth-Sun distance), with about two-to-four years of data.

But for wide binaries, which are at separations that range from perhaps 2,000 up to 30,000 Astronomical Units, it would take centuries of data with the current precisions we can obtain, observationally. We cannot determine the properties of individual systems with Gaia, and therefore we cannot know for certain how these systems are behaving. The technique du jour that is being used to try to extract this information, including from:

- Kyu-Hyun Chae, who finds a deviation from Newton’s laws and an agreement with MOND,

- Indranil Banik, who finds a strong disagreement with MOND and a perfect agreement with Newton’s laws,

- and Xavier Hernandez, who finds an agreement with Newton’s laws at distances below 2,000 A.U. but a disagreement, and better agreement with MOND, at distances above it,

is to instead take a statistical approach, averaging together the data from large numbers of wide binary systems (thousands of them) with similar separation distances, to extract the overall behavior.

You might wonder: how can different groups, using the same data, arrive at such opposing conclusions from one another?

The answer is simple: different groups disagree as to which systems should be including in the analysis, because they disagree as to which systems are legitimately wide binaries (i.e., two stars, separated by a large distance, that are gravitationally bound together) versus which systems are simply coincidentally two stars located physically close to one another: like two ships passing in the night. We don’t have the sufficient data to make those determinations for any individual systems, which tells us that the data simply isn’t good enough to draw any responsible conclusions.

In other words, the science of wide binaries, in determining the gravitational behavior of these systems, is not yet mature.

How do we make sense of the Universe?

You might think that better measurements of wide binaries is going to be the key to resolving this conundrum, but that’s unlikely: it will take decades-to-centuries of data, at least, before we’re able to definitively tell which systems should and shouldn’t be included as bona fide wide binaries, and the wider the orbit, the longer the baseline of data that we’ll need. It makes a lot of sense that we’re doing the best science we can with the novel data that we’ve acquired, but it’s the professional opinion of many — including me, for whatever that’s worth — that the problem of selection bias, where the conclusions change dramatically depending on which objects are chosen to be part of the sample, is too great at this moment in time to allow us to draw responsible conclusions about the Universe from this approach.

However, it isn’t premature to note the different realms where the different ideas about our Universe make different predictions from one another. A Universe with dark matter, a Universe ruled by MOG, and a Universe ruled by MOND, make predictions for:

- Solar System scales,

- intermediate (i.e., wide binary-esque) scales,

- galaxy scales,

- galaxy cluster scales,

- colliding galaxy clusters,

- and cosmological scales.

Interestingly, MOG matches dark matter’s predictions for the first two, MOND’s predictions for the third, and appears to agree with dark matter’s predictions for the latter three, although that last one is controversial.

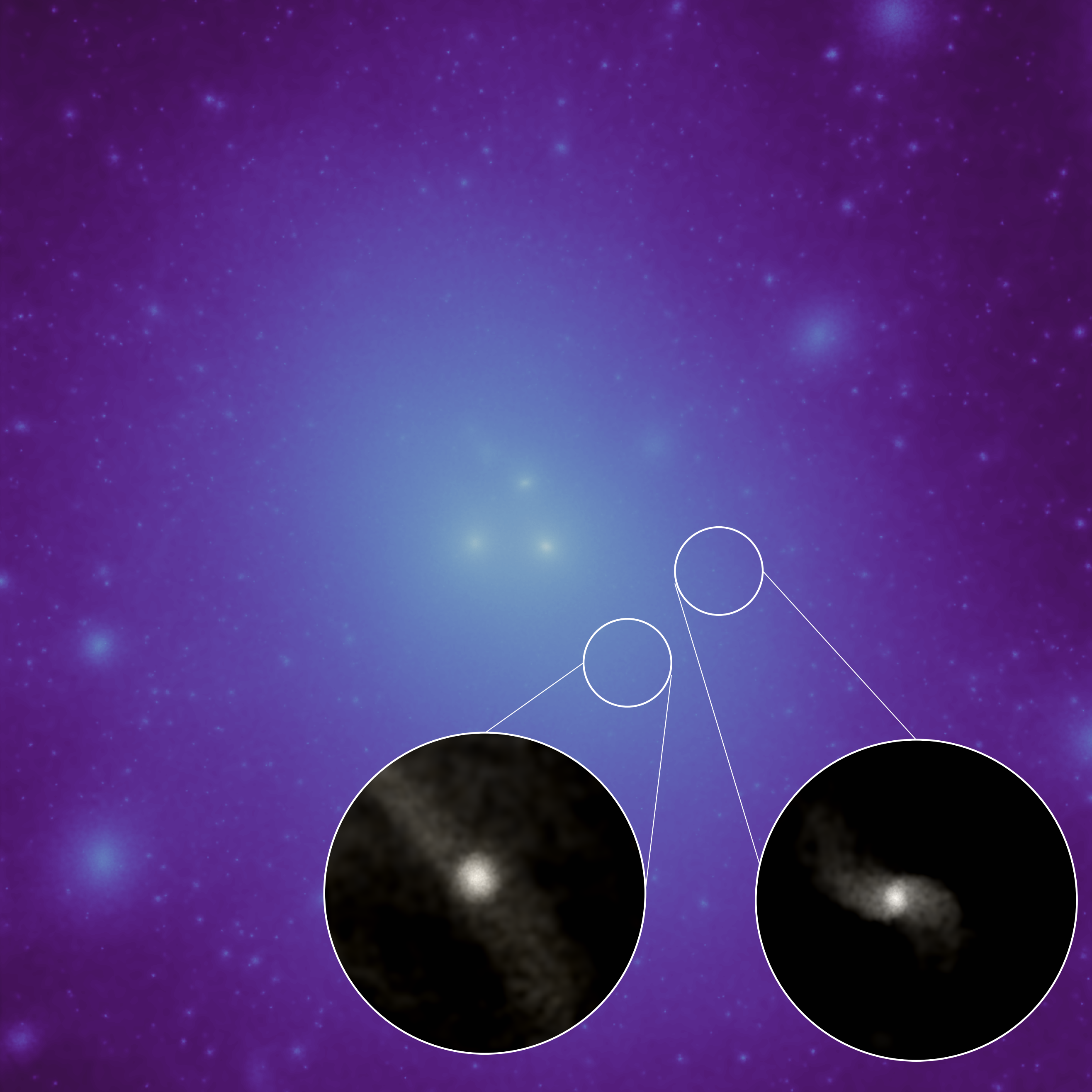

However, there’s a very big problem for MOG — one that I would argue is a dealbreaker of a problem for the theory — that rarely gets discussed in the literature. MOG has the remarkable property that gravitational effects can appear where the matter itself is not: part of the non-local nature of the theory. This is what enables post-collisional galaxy clusters, which separate the majority of the normal matter from the host cluster that contains the individual galaxies, to have gravity where the mass is not within the framework of MOG. (Whereas, in the dark matter interpretation, the gravitational effects, revealed by lensing data, are a result of the non-luminous dark matter that is present alongside the individual galaxies.)

The problem is that we have numerous examples of pre-collisional galaxy clusters in the Universe: where galaxy clusters are nearby one another, but have not yet collided. Their normal matter is still located within the clusters themselves. In the MOG framework, you should still expect a non-local gravitational signal: where the gravity appears to be affecting regions differently from where the mass is located, whereas in the dark matter framework, you’d expect it to behave more simply, as two independent clusters with their own lensing signals. In fact, the data has been in for a long time — for decades — indicating that the behavior is purely local.

This is the key observation that poses difficulties for MOG, and arguably the “problem area” it must address, as well as the currently unresolved issues on cosmological scales, that must be overcome. It’s nice to know that different theories and different ideas make different physical predictions for what we should see in the Universe, as that’s exactly what we require if we’re going to figure out which scenario best matches our reality. It’s nice to know that wide binaries will either agree with MOG-and-dark matter or MOND, and that when our measurements get good enough, that will be one way to discern between them.

But wide binaries themselves are not going to be the key test area for MOG: those will be determined by the physics of pre-collisional clusters and cosmological scales, as those are the key areas of disagreement between MOG and dark matter-based theories. It’s absolutely a good exercise to see where the strengths and weaknesses of various ideas lie, but it’s even more important to not fool yourself by only looking at the pieces of observational evidence that support your preferred ideas.

In physics, it’s the weakest aspects of your theory that always deserve the most scrutiny, as only the most robust theories will stand up to them all. At this point in time, it’s the difference between pre-and-post-collisional clusters that poses the greatest difficulty for MOG, and that’s where the key testing ground should lie for that theory: not in wide binaries, where the data is not yet good enough to make accurate determinations of the force laws that govern our Universe.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!