136 – New Iceland – A Forgotten Nordic Colony In Canada

n

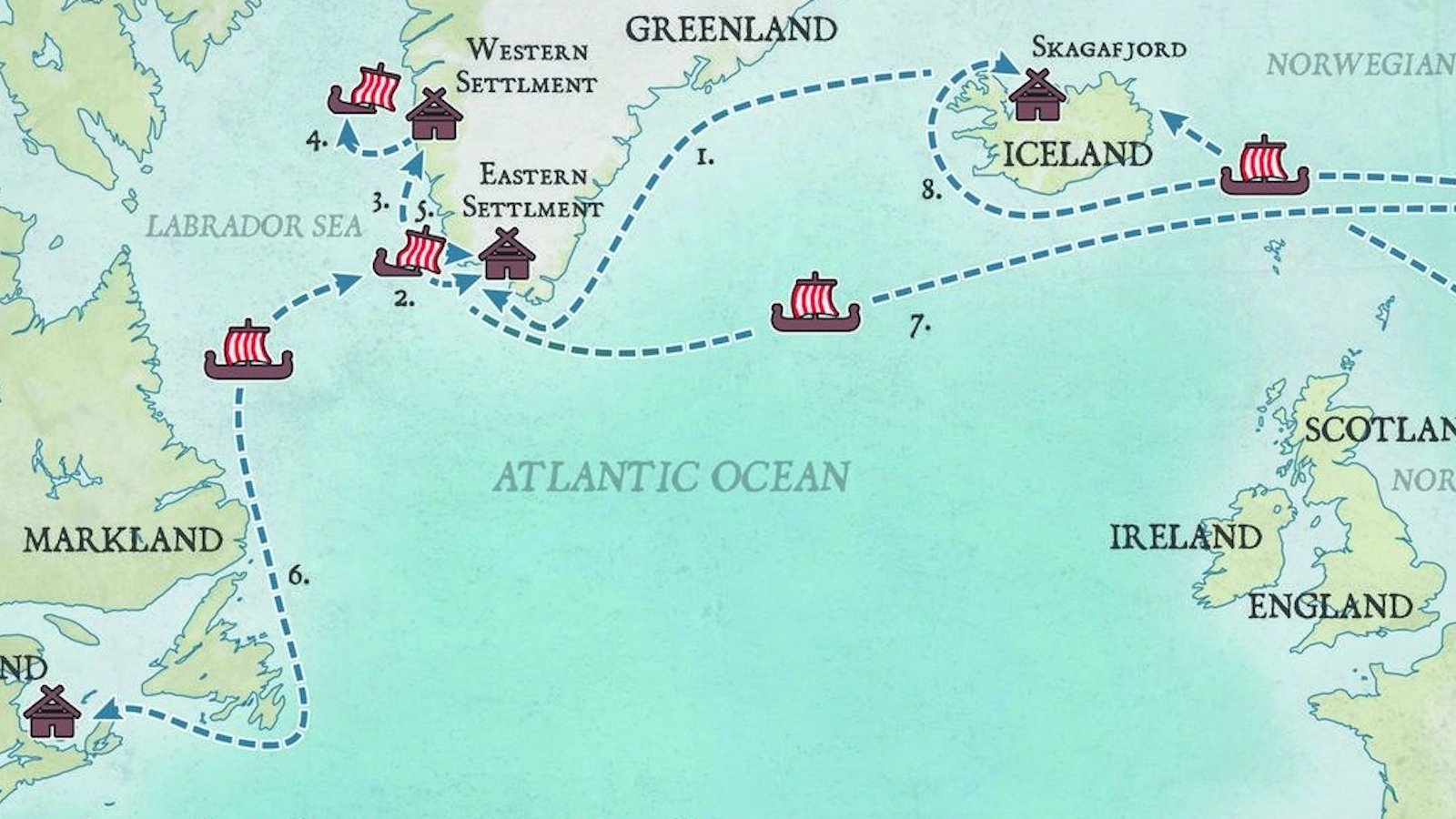

When it comes to the discovery and colonization of America, Iceland can claim a longer pedigree than all other European countries. The Icelandic explorer Leif Eriksson (970-1020) was the first European in recorded history to set foot in North America, where he named three areas:

n

n

n

n

The USA celebrates each October 9th as Leif Eriksson Day, although he probably never set foot on what is now US soil.

n

More speculative, or just plain wrong, are theories that hold that Norsemen penetrated as far inland as Minnesota (where the Kensington Runestone, dated at 1030 but in all likelihood a recent forgery, was long held to be a true artifact of such an incursion) via the Hudson Bay and/or the Great Lakes. It is intriguing, however, that exactly this area of the continent was to be later heavily colonized by Scandinavians. Many Minnesotans are of Scandinavian descent.

n

A bit further north, there even was a flourishing Icelandic colony that for a while functioned as a semi-independent republic within the still fluid framework of Canadian westward expansion. Nyja Island (‘New Iceland’) was located in the Canadian province of Manitoba, on the western shore of Lake Winnipeg. It was the result of large-scale Icelandic emigration to Canada, especially in the late nineteenth century (in 1875, a volcano on Iceland erupted, exacerbating already precarious living conditions).

n

The areas of Icelandic settlement covered the area north of Boundary Creek as far north as Hecla Island, with Gimli in the Riverton area the focal point of Icelandic immigration. This was mainly due to the efforts of Sigtryggur Jonasson, an earlier Icelandic migrant, who wrote a pamphlet on behalf of the Canadian government entitled Nyja Island I Kanada (‘New Iceland In Canada’) and went back to Iceland to convince Icelanders to join him across the ocean.

n

Jonasson was part of an expedition to the north of Manitoba to find a suitable location for the colony. New Iceland had to be isolated, have good soil for farming and be close to a lake, for fishing. The only drawback of the eventual site, 18 miles upstream from the Icelandic River: an abundance of grasshoppers. For his efforts, Jonasson is remembered as the ‘Father of New Iceland’.

n

The very first Icelandic town in New Iceland was named Gimli, Icelandic for ‘Paradise’. Conditions were far from idyllic, however: low on resources, many colonists didn’t survive the first, harsh winter. The following year, 1876, saw the arrival of the Stóri Hópurinn, the ‘Large Group’ of 1.200 immigrants, swelling the colony’s population to nearly 2.000. At the close of that same year, the colony was ravaged by a smallpox epidemic, killing off as many as 500 colonists and resulting in a quarantine on the whole of New Iceland that lasted until the middle of next year.

n

In order to help the ailing and despairing colony to survive, a form of self-government was set up, modeled on the Althing back home. The Vatnsthing (‘Lake Parliament’) ruled over four districts:

n

- n

- Vidinesbygd (‘Willow Point Community’, now the Gimli District);

- Arnesbygd (‘Ames Community’);

- Fljotsbygd (‘Icelandic River Community’, now the Riverton District); and

- Mikleyjarbygd (‘Big Island Community’, now Hecla Island).

n

n

n

n

n

“The Colony of New Iceland was recognized by the Canadian government as a separate nation with full jurisdiction on immigration, taxation and legal matters,” the website mentioned under comment #2 claims. No evidence of this exists. In any case, emigration continued, however, to better lands as far south as Dakota. In 1881, New Iceland barely counted a hundred inhabitants. The local newspaper folded, the government of New Iceland disbanded itself.

n

New Iceland fell on better times a few years after the great exodus, when fishing, farming and freighting offered better job opportunities. New Icelandic immigrants set up the towns of Riverton and Arborg (Icelandic for ‘Riverton’). In 1893, New Iceland was almost back to its previous numbers. In 1887, all of New Iceland was incorporated into Manitoba as the Gimli Municipality, thus ending the brief, fledgling existence of the first neo-Scandinavian state on American soil since Leif Eriksson’s brief transatlantic adventure.

n

In over a century of its existence, Gimli has welcomed a steady trickle of Icelandic immigrants, but also many Ukranian and Native newcomers, lending the tourist town a multicultural ambiance. The Icelanders, in turn, have impressed their identity upon Manitoba; the local university offers courses in Icelandic language and culture.

n

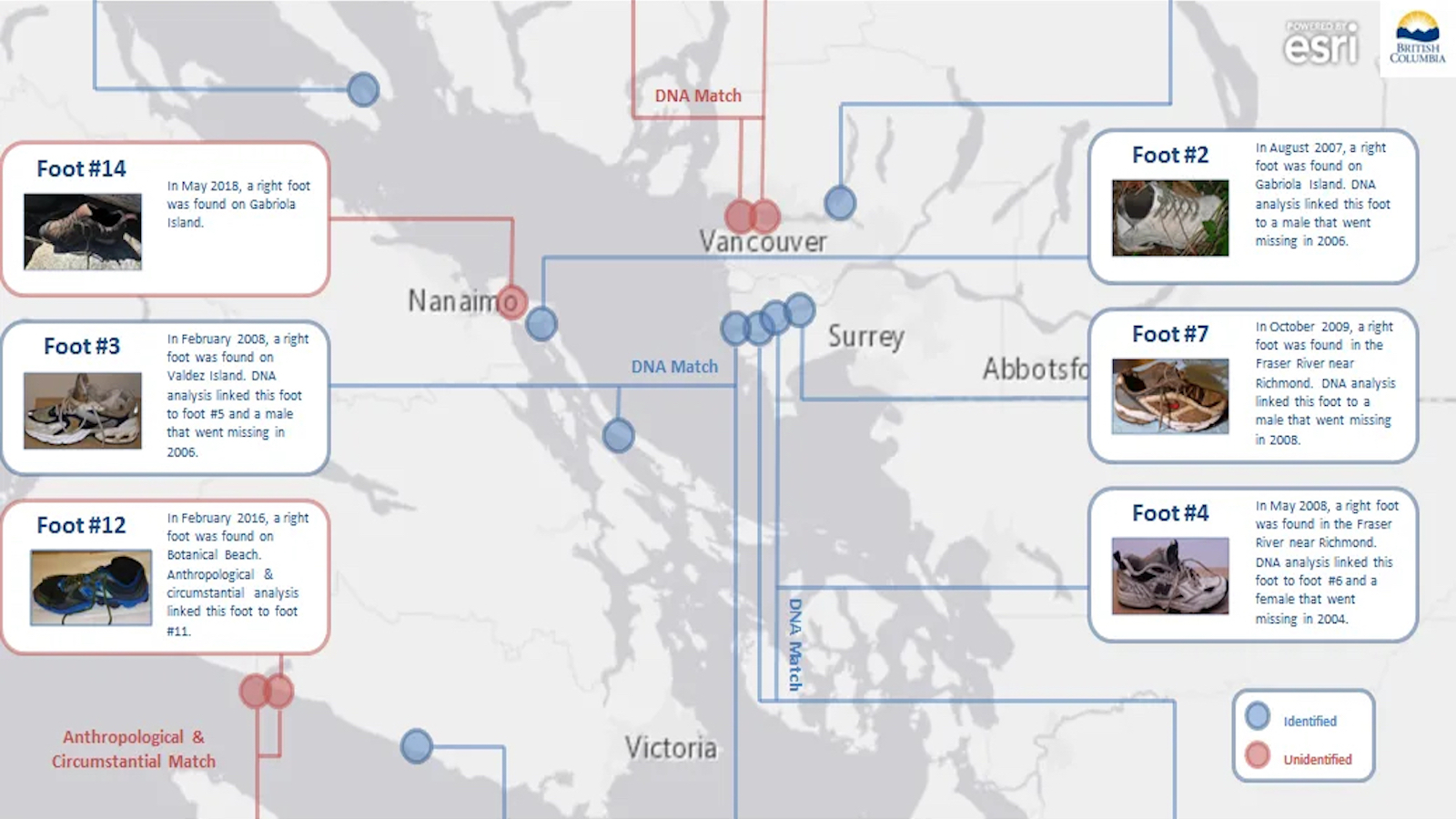

This map, which covers the southern quarter of Lake Winnipeg’s western shore, was suggested to me by James L. Erwin, and can be found here: http://timelinks.merlin.mb.ca/imagere1/ref0172.htm

nn