The Kingdom of Prester John, Christianity’s Imaginary Ally

In 1145, the Syrian bishop Hugo of Jabala brought Pope Eugene III the news of the Muslim reconquest of Edessa, an important Crusader stronghold in the Holy Land. The bishop softened the blow – and hoped to encourage the Pope to a new Crusade – with tales of a mighty Christian king attacking the Muslims from behind: Prester John, a descendant of one of the Three Magi and ruler of a Christian Empire beyond the Muslim-ruled lands in India, on the very edge of the world then known to Europe. According to Otto von Freising’s contemporary Chronicles, Hugo spoke of “a certain Prester John who lives in the Far East, beyond Persia and Armenia, King and Priest, Christian but Nestorian (1), having waged war against the Persian and Median dynasty of the Sarmiads, having chased them from their capital Ectabana.” This raised the possibility of a Christian pincer attack on the Muslim world.

Twenty years later, a letter addressed by Prester John to the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenus caused a great stirring of hope in all of Christendom. Pope Alexander III sent out an envoy to the Prester, but without result (the fate of the papal diplomat is unknown). The letter, however, remained a powerful tonic to a Europe feeling hemmed in by the Muslim ascendancy in the Middle East and Northern Africa. It was copied (and embellished) for many decades afterwards. The letter described a Christian empire with 72 tributary kingdoms, in an area of the world with a fantastic ecology inhabited, among others, by vampires and dog-headed people. The Fountain of Youth and a river flowing from Paradise itself and filled with precious stones helped complete a picture of thrilling exoticism. And of perfect piety, happiness and wealth: “All Christian values are respected to the letter. Theft, greed and lies are unknown. There is no poverty.”

But the letter was a forgery, Prester John as virtual as he was virtuous, the legend literally too good to be true. All Prester John ever was king of, was Wishful Thinking. Prester John’s fictional empire proved as movable as the imagination of beleaguered Christianity required. First inferred in India, the kingdom was later situated in Central Asia, and eventually assumed to be in Africa. The ease of these huge locational shifts was due not just to Europe’s dim perception of geography at the time, but also to the elasticity of the contemporary concept of ‘India’, which in its broadest interpretation could stretch all the way from Africa to China.

Whatever its location du jour, Prester John’s legend required his kingdom to be beyond Muslim lands, and in a little-known corner of the world. The last, longest and strongest association of the legend was with Abyssinia (2) – mainly because, apart from conforming to the legend’s geographical requirements, it also did happen to be a Christian empire. In his Mirabilia (1323),Jourdain de Séverac identified the Abyssinian Negus (i.e. Emperor and supreme leader of the Abyssinian monophysite church) with Prester John, spurring European expeditions to the African empire. In 1490, the Portuguese explorer Pêro da Covilhã managed to convey a letter from the king of Portugal to the Negus… even though the letter itself was addressed to Prester John. This must have surprised the Negus, but that did not stop Europeans from continuing to the conceit – even though the Ethiopians in their intermittent contacts with European Christendom tried to clarify that their Emperor certainly wasn’t anyone’s “Prester”. Only in the 17th century did Europeans realise their mistake, and Prester John finally faded from maps, and from memory. Prester John might never have been real, but his influence can be felt clearly; in the push of European exploration around Africa towards India and Ethiopia, and in cultural references ranging from William Shakespeare and Umberto Eco to Marvel Comics (3).

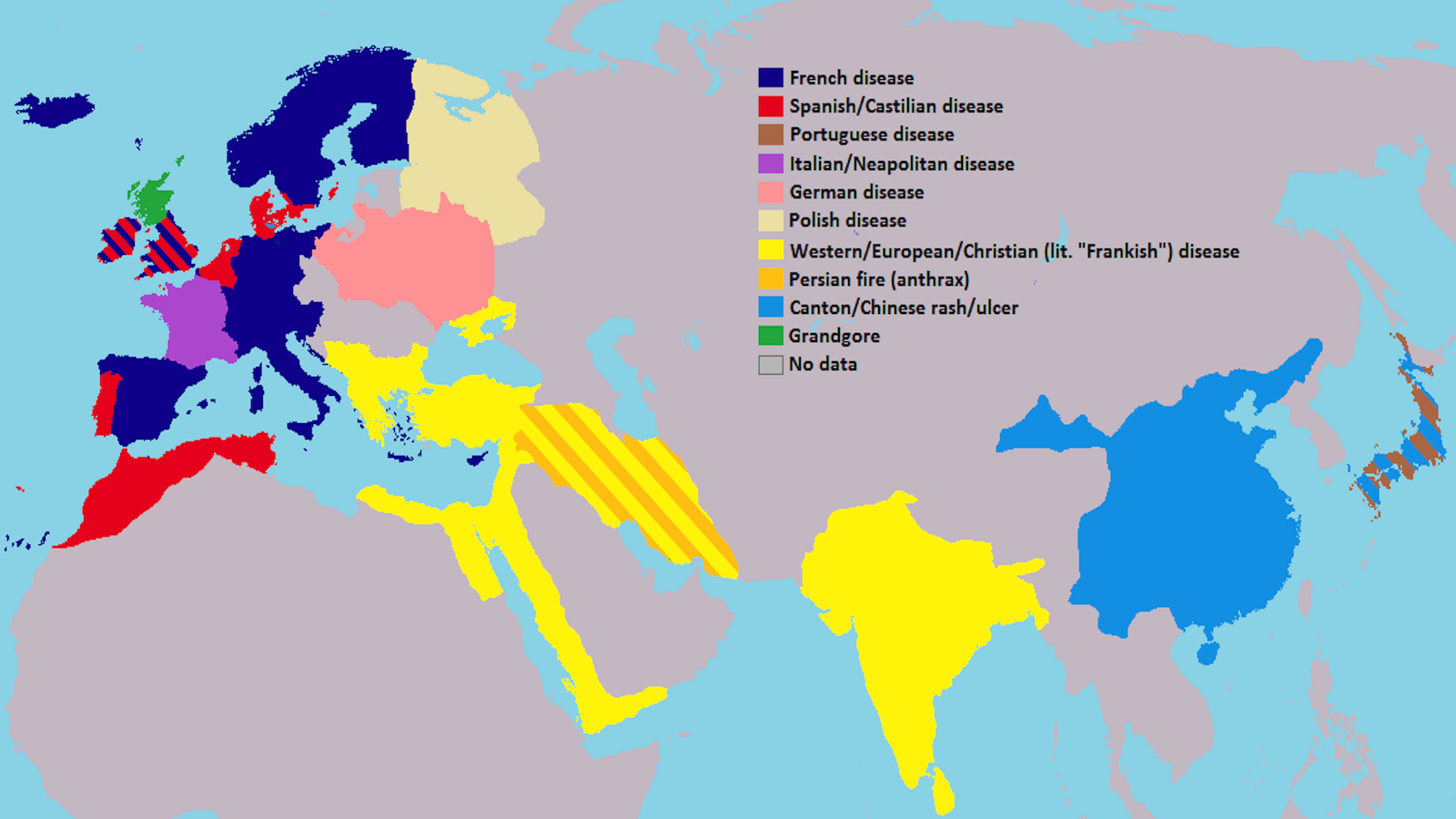

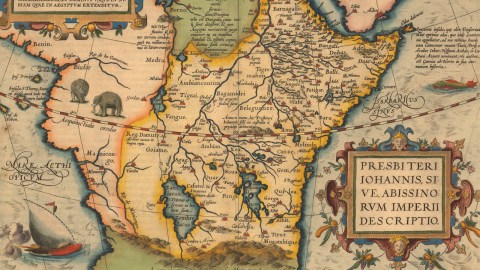

This map, dating from the 1570s, still takes Europe’s devout wishes for geopolitical truth. It was produced in Antwerp by Ortelius, entitled A Description of The Empire of Prester John, Also Known as the Abyssinian Empire. It delineates Prester John’s empire as follows: its borders almost reach north to Aswan (noted on the map as Aßuan) on the Nile, then follow the Nile, Niger and Manicongo rivers south to the Mountains of the Moon (Lunae montes, hinc Austrum versus Africa veteribus incognita fuit: The Mountains of the Moon, ‘Africa south from here was unknown to the Ancients’). The kingdom extends from these western and southern borders all the way to Africa’s eastern shores.

Ortelius’ map mixes up familiar and imagined names and locations into an intriguing mess of real and imagined geography.

* In northern Africa are Barbaria (the Barbary Coast) and Egypt, on the western African coast are other place names that still sound familiar: Benin, Biafar (Biafra?), Rio de los Camarones (Cameroon), Manicongo (Congo), Angolia (Angola).

* The Mountains of the Moon in Central Africa were known to Greek geographers as early as Ptolemy (although he might have referred to the Kilimanjaro instead). On this map, they are situated far south of the Equator. Mozambique, named by Portuguese explorers in the late 15th century, possibly after a lokal sheikh called Moussa ibn Mbeki, is on the coast and appears north of the Mountains of the Moon.

* The interior is dominated by a few great lakes, probably a garbled reference to the actual Great Lakes. They are named Zaire lacus (or Zembre lacus), near which amazons live and in which sirens swim, and Zaflan lacus. Zaire, the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1971 and 1997, is a Portuguese corruption of the Congolese word nzere, ‘the river that swallows all rivers’.

* In the interior of Prester John’s kingdom is a legend that appears to read: ‘Mount Amara, here the sons of Prester John are held in captivity by [a] governor’.

* On the Arabian peninsula, two cities are referenced: Mecha, patria Mahumetis (‘Mecca, the home of Muhammad’), and Medina Talnabi, ubi Mahumetis sepulcrum magna frequentia visitur (‘Medina Talnabi, where the tomb of Muhammad is visited with great frequency’). Two other cities, Aden and Zibir (possibly Sana’a) are located in (or to)the south of Aiman, quae olim Arabia Felix (‘Yemen, formerly Happy Arabia’).

This map was taken from this page at Princeton University Library. The page quotes Jonathan Swift, as “[t]his is certainly one of the maps that [he] had in mind when he wrote: So Geographers in Afric-maps With Savage-Pictures fill their Gaps; And o’er uninhabitable Downs Place Elephants for want of Towns – On Poetry: A Rhapsody (1733)

Strange Maps #434

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) a Christian heresy regarding Jesus as two persons, human and divine, that at one time spread deep into Central Asia.

(2) synonymous with the Ethiopian Empire, which existed from 1137 until well into the 20th century. After the coup d’etat in 1978 which deposed the country’s last emperor, it has generally only been referred to as Ethiopia.

(3) in Much Ado About Nothing, Baudolino and the Fantastic Four, respectively.