Bodyworld: the Artography of Fernando Vicente

The word atlas conjures up two very different ways of perceiving the world. The first one that springs to mind is of a book containing a planet-spanning collection of maps, exhaustively descriptive. And then there’s Atlas the Greek titan, condemned to carry the weight of the entire world (1) on his shoulders. The latter meaning begat the former: when cartographers started publishing map collections in book-form, they often included in the frontispiece of those collections an image of the world-bearer.

Spanish artist Fernando Vicente’s artography (2) revisits this fusion of the descriptive and the symbolic, but expands the concept to its literal conclusion. Superimposing human and animal forms onto the countries and continents of a map, Vicente transforms familiar geographic contours into surprising new constructs. Maps become living creatures – although some ostensibly formerly living ones – and many of which have an ominous, unnerving quality. Maybe that’s because of Vicente’s predilection for slicing open his subjects, their exposed anatomy/geography investing them with the same morbid quality evident in Bodyworlds, the famous travelling exhibition of plastinated and dissected human bodies.

Not that Vicente’s inspiration needs that movable mortuary. Zoomorphism’s (3) pedigree in cartography is centuries old. Earlier posts on this blog have covered maps showing Asia as a horse (4), Europe as a queen (5), and the world as a cloverleaf (6). These bizarre old maps are often catalogues of obscure symbolic references, now half forgotten or hard to fathom. Modern examples are usually easier to grasp. They can be the result of the blatant suggestiveness of geography itself, as with the Southern Ontario Elephant (7). Other times, zoomorphic cartography is actively landscaped into being, as in the city laid out to resemble Evita Peron’s head (8), or in Southern Sudan’s proposed zoomorphic provincial capitals in (9).

Vicente’s work is more related to the Southern Ontario Elephant than to the Southern Sudan Rhinoceros: the forms are not imposed on a landscape, but merely teased out of it, and onto the map. One could argue that maps are not made for such teasing. Essentially utilitarian, they are manuals more than poems. But nothing transforms the randomly mundane into enjoyable art like a map, as any cartophile will appreciate. Vicente transforms this passive appreciation into an activity, probing maps for hints of non-geographic forms: is this isthmus an elbow? Can that mountain ridge be a brow?

This process must involve a lot of turning of maps, and squinting at them. The familiar shapes of countries are such strong mental images that the artist needs to get past them first. Take, for instance, his dolphin-shaped map of Mexico. Your average representation of Mexico, on a map with north up, suggests nothing so much as Mexico itself. But give it a quarter-turn and have east facing up: if you’re looking for life-forms, that Yucatan peninsula now looks pretty much like some kind of tail. And then other parts of the country begin to look like other parts of the animal that eventually took shape: the snout pointing towards San Diego, the dorsal fin where the Gulf meets the Texas-Mexico border.

A similar process might have created this map of Elephantine Argentina (or the Argentine Elephant), its trunk suggesting itself after the map had been given a quarter turn to the right. The province of Buenos Aires, bulging eastward into the South Atlantic, is the elephant’s round cheek. Some liberty is taken by having stumpy Misiones province fan out into the elephant’s ear. In a nice touch, the elephant’s trunk curls back so that its tip coincides with the Falkland Islands, a British possession claimed by the Argentines as the Islas Malvinas.

In another take on Latin America, the entire continent is turned upside down to reveal a pregnant, cross-sected woman. The Andes is her spine, the territorial bulges on either coast are transformed into the curves of her belly and rump. The womb coincides with Brazil, as if Latin America is pregnant with its own nascent superpower.

A straight-up map of Africa morphs into the portrait of a black woman by using the Horn of Africa as the base of her forehead and the roundness of West Africa as the back of her head. That Horn proves a most versatile promontory indeed: turn that map upside down and it now is the nose of a Holbein-inspired portrait. Africa’s western coastline serves as the border between cap and face.

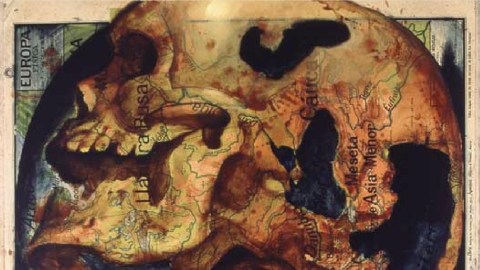

Moving deeper into Bodyworlds territory, a map of Europe, east facing up, is turned into a cartographic vanitas (10) by cleverly disguising most of Western Europe as the upper vertebrae, Scandinavia as part of the jaw and the White Sea as the mouth of a human skull.

Fernando Vicente Sánchez (Madrid, 1963) is a cartoonist, illustrator and painter. He has produced work for Spanish magazines and newspapers, illustrated book and record covers, exhibited across Spain and published several books of his work. To see more examples of his zoomorphic artography, see his blog. Under Pintura, look for Atlas (and also have a look at Anatomias, displaying a similar fascination for dissecting humans – this time literally to see what makes them tick).

Here’s just one more of Fernando Vicente’s fascinating maps: Great Britain and Ireland disguised as a couple of dead rabbits.

Strange Maps #488

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) actually Atlas was condemned to support the pillars of heaven, but in the imagination of sculptors and other artists, the sentence was soon commuted.

(2) where art meets cartography, but feels too grandiose merely to be labelled ‘map art’.

(3) the presentation of an inanimate object as a living creature, in this case the continents and/or countries on a map as animals or humans.

(4) #165.

(5) #141.

(6) #87.

(7) #340.

(8) #346.

(9) #477.

(10) a work of art, often a painting, symbolising the vanity of life by showing its transience, usually by the prominent display of a skull.