Greenland’s Revenge: Denmark Frozen Solid

A map in Cees Nooteboom’s novel In the Dutch Mountains shows the Netherlands improbably extended, via a narrow corridor, to a large territory on the Balkans (1). The idea of the map (and the novel) is to provide the Netherlands, well-organised to the point of dullness as it is, with a romantic counterweight, a colony on the rough edges of civilisation. Denmark doesn’t need such a fictional contrepoids. It has Greenland.

“From an artistic and cultural perspective, Greenland has always been the Orient of Modern Denmark,” said Danish artist and curator Khaled Ramadan in a text figuring in a 2006 exhibition on ‘Rethinking Nordic Colonialism’. Greenland has been the majestic canvas on which domesticated Denmark could project its national dreams of greatness – even if they came with a serious risk of frostbite.

Like the Netherlands, Denmark today is a small, unprepossessing country, minding its own business in its corner of Northwestern Europe. But to both countries are attached the phantom limbs of empires past.

The Dutch are clinging, ever more tenuously, to half a dozen islands (2) in the Caribbean, but they have colonial legacies from the Hudson Valley over Cape Town to New Guinea. The Danes once lorded it over much of England, then called Danelaw, and more recently held sway over bits of the Caribbean (3) and India (4). Of its Arctic empire, which once encompassed Norway and Iceland, only the tiny Faeroer Islands remain, and Greenland.

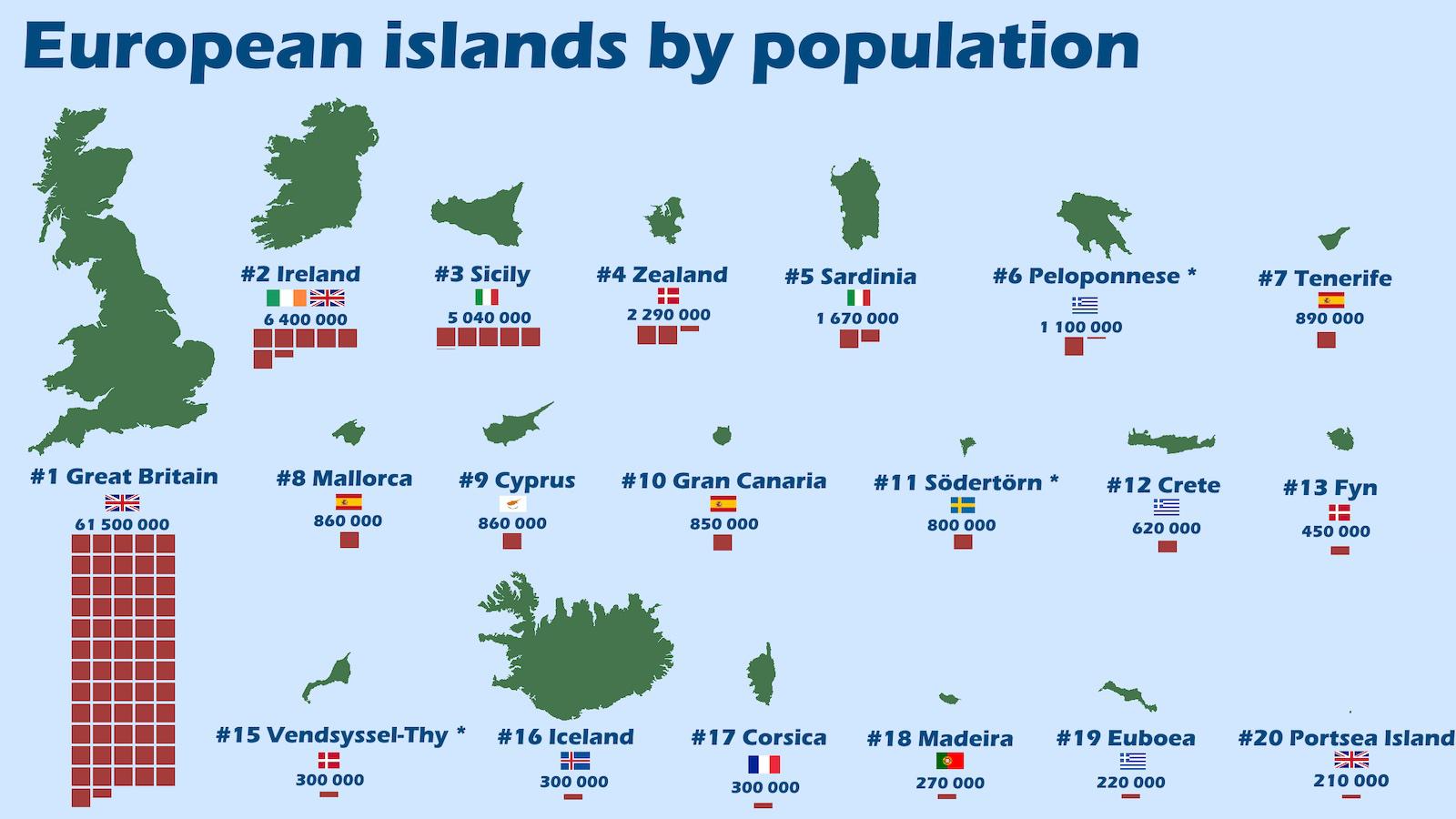

Greenland simultaneously dwarfs the Mother Country, and is dwarfed by it. In size, it is the world’s largest island (5), and about 50 times larger than Denmark. In population, it’s a few thousand Inuit short of 60,000 inhabitants, which only just measures up to Denmark’s 10th-largest city, Kolding.

In spite of its numerical advantage, Denmark has not swamped Greenland with colonists to outnumber the native Inuit, and further to its credit, it has been preparing Greenland via a decades-old autonomy for an eventual independence. For the moment, the Danish government maintains sole responsibility for the defence and foreign affairs of Greenland (6). Until its natural wealth is adequately exploited, Denmark provides a yearly subsidy in excess of $10,000 per Greenlander.

Nordic Colonialism, to re-use the phrase being rethought by Mr Ramadan, doesn’t seem like such a bad thing, in this case at least: rather benevolent, and nudging towards a happy end. But any colonisation, however benevolent, implies the imposition of social values, models and roles on the colonised. This has the potential to fray the social fabric of native communities. Strikingly, alcoholism and suicide are rife in Greenland, much in the same way these twin scourges have ravaged other colonised peoples.

The Aborigines of Australia, for example. In levels of poverty, rates of suicide and alcoholism, and life expectancy, Australia’s First Peoples are doing a lot worse than the national average. One poetic act of native revenge was effected on 26 January 1988, Australian Bicentenary Day. Exactly 200 years after Arthur Phillip of the so-called First Fleet had claimed Australia for Britain, the Aboriginal activist Burnum Burnum landed at Dover and planted the Aboriginal flag on the white cliffs, claiming Britain for his people.

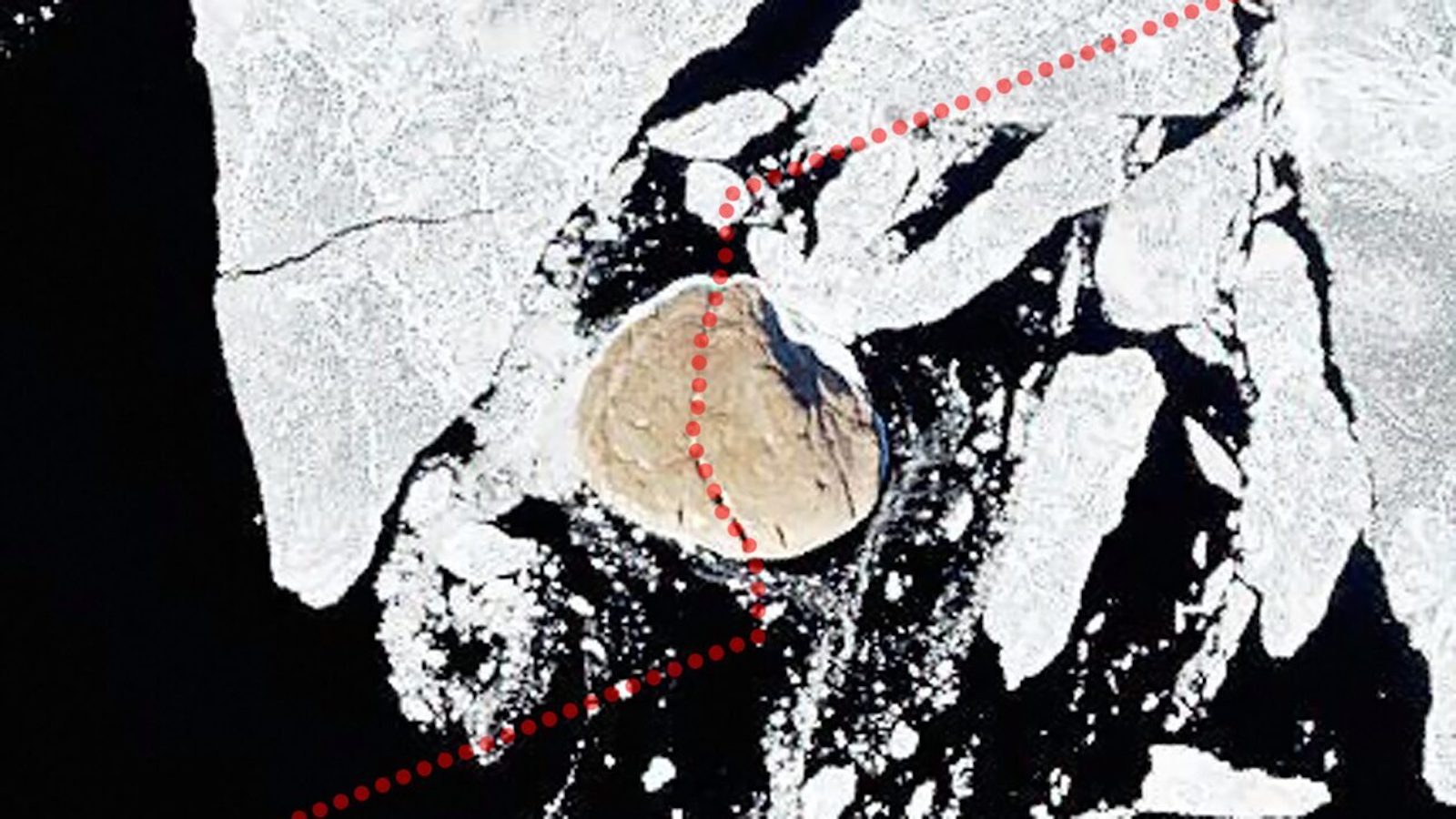

This map depicts a similar role reversal, with the Danish colonisers and colonised Greenlanders trading places. Greenland’s familiar topography – a white, empty core surrounded by a thin crust of small settlements – is transposed on the equally familiar map of Denmark. The coastline is extremely jagged, as is the Greenlandic one, from the erosive force of the gletschers flowing down from the massive central ice shelf. This is what Denmark might look like if the Inuit had colonised Denmark – and brought along their climate.

The map legend and the city names are in both Danish and Greenlandic – as they are on maps of Greenland, but here, it’s the Danish names that are ‘native’ and the Greenlandic ones that have been imposed (7). Reflecting the balance of colonial power, it’s the native names that are between brackets. The ‘colonial’ name is in capitals.

As in Greenland, large tracts of the interior are named after people – Greenlanders instead of Danes, this time. The best-known Greenlander to the outside world perhaps is Jonathan Motzfeldt, who served as the first and third prime minister of autonomous Greenland. He gets a large Land named after him in the south of Jutland.

The intended effect of this map is for the Danish to experience being on the receiving end of colonisation. But in a double irony, most of the Greenlanders lending their name to frozen pieces of Denmark have… Danish surnames.

Many thanks to Mikael Parkvall for sending in this map, found here at the website for the exhibition on Rethinking Nordic Colonialism. The map was designed by Inuk Silis Høegh and Asmund Havsteen-Mikkelsen.

Strange Maps #525

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) I had seen this map only once, in the novel’s original Dutch-language version (title: In Nederland) and didn’t have a copy. Many thanks to Lowell G. McManus for tracking down this online version, found here at De Contrabas.

(2) Actually, more like five and a half. Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Saba, St. Eustatius, and the southern half of St. Maarten (the northern bit being French) together used to form the Netherlands Antilles, a separate ‘country’ within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Presently, the count is three countries (Aruba, Curaçao and St. Maarten) and three ‘special municipalities’ (Bonaire, Saba, St. Eustatius).

(3) The Caribbean bits are now the US Virgin Islands. The Danes held on to what they called the Jomfruøerne until the 1916 treaty that sold them to the States. Some place names on St. Croix (Christiansted), St. John (Hansen Bay) and St. Thomas (Charlotte Amalie, after a queen-consort of Denmark-Norway) still reflect the Danish era.

(4) A Danish Museum in the old Danish Fort are all that remains of the Danish colony of Tranquebar (1620-1845), now the small seaside town of Tharangambadi in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

(5) The world’s largest island that is not a continent, to be exact. The world’s largest island per se is Australia (3,269,629 sq. mi, 8,468,300 km2), but it is also considered the world’s smallest continent. At 836,330 sq. mi (2,166,086 km2), Greenland is the largest non-independent territory in the world. If independent, it would be the world’s 12th-largest country, between the DR Congo and Saudi Arabia.

(6) This includes arguing with Canada for sovereignty over tiny Hans Island, and with the Russians for sovereignty over the North Pole (and, more to the point, over the natural resources in the Arctic seabed).

(7) My Greenlandic is rather wobbly. Can anyone provide translations?