Down the Rhine and Back in Time: A Map from Tourism’s Younger Days

Modern tourism is born of the Grand Tour. From the 17th century onwards, the brahmins of Britain travelled across the Continent for the twin purposes of education and entertainment. The Tour, an itinerant masterclass in antique culture and contemporary manners, gained popularity throughout the subsequent centuries. The concept of leisure travel spread to other national elites, and to the middle classes. Eventually, with the onset of mass transport and paid holidays, it came within reach of the working classes.

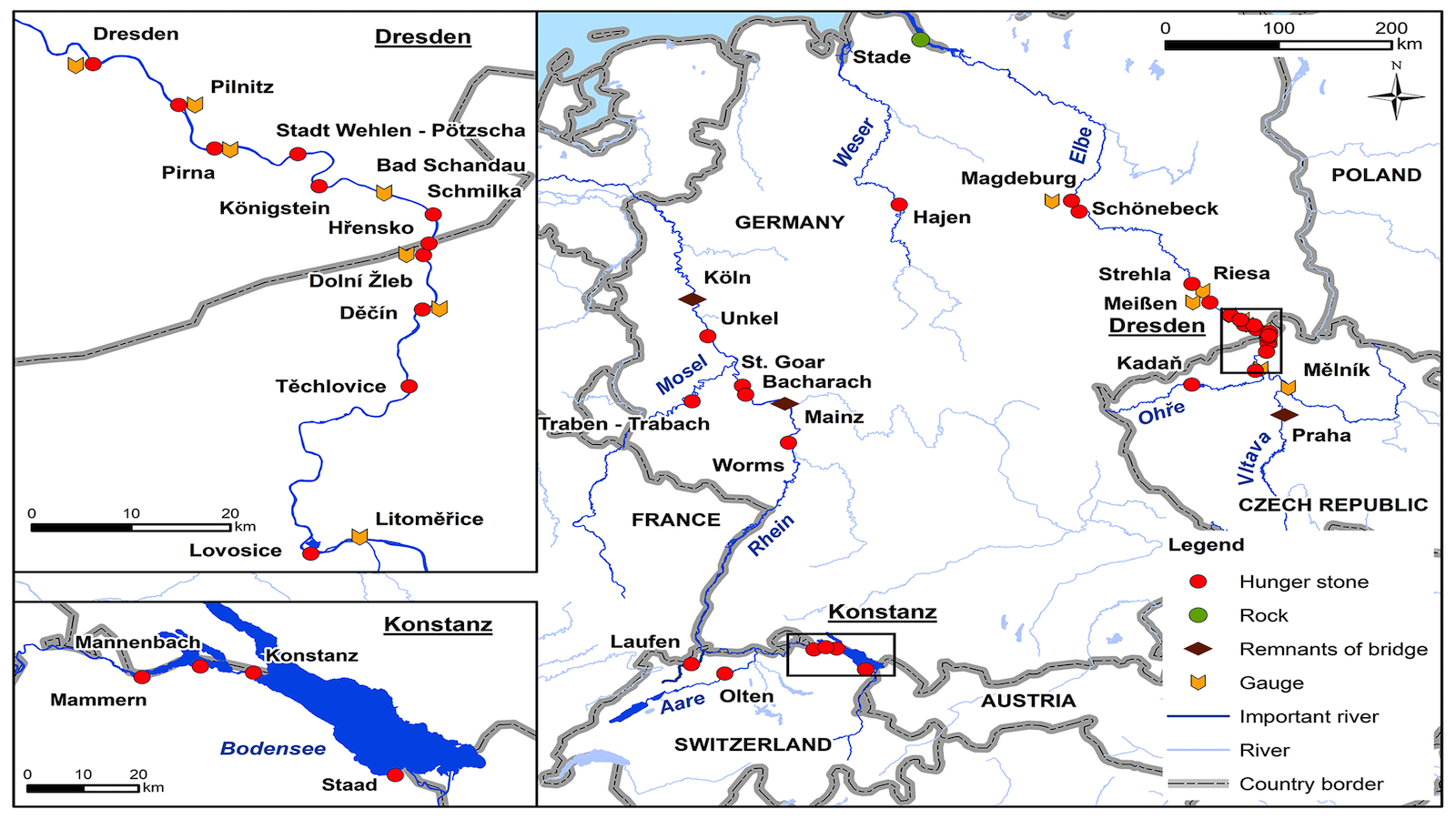

Italy, with its rich mix of treasures from classical antiquity, culinary delights, and friendly climes, was the obvious first target of the Grand Tour. Another early tourist hotspot was Germany’s Rhine Valley. Not only because of its natural splendour and architectural heritage, but also because of its very topography. In the days before rail, the river was a natural conduit for the leisure traveller, much as it had been for the traders, artists and builders who had unwittingly created the attractions along the banks.

‘Tourism’ – a word first appearing in print in 1822 – quickly turned professional, attested by the rapid spread during the 19th century of Hotel Bristol as a generic name for overnight accommodation for the weary tourist [1]. Tourism also produced a new type of cartography – the tourist map. These maps were explicitly designed to be alluring, to include and reflect the leisurely enjoyment of travel.

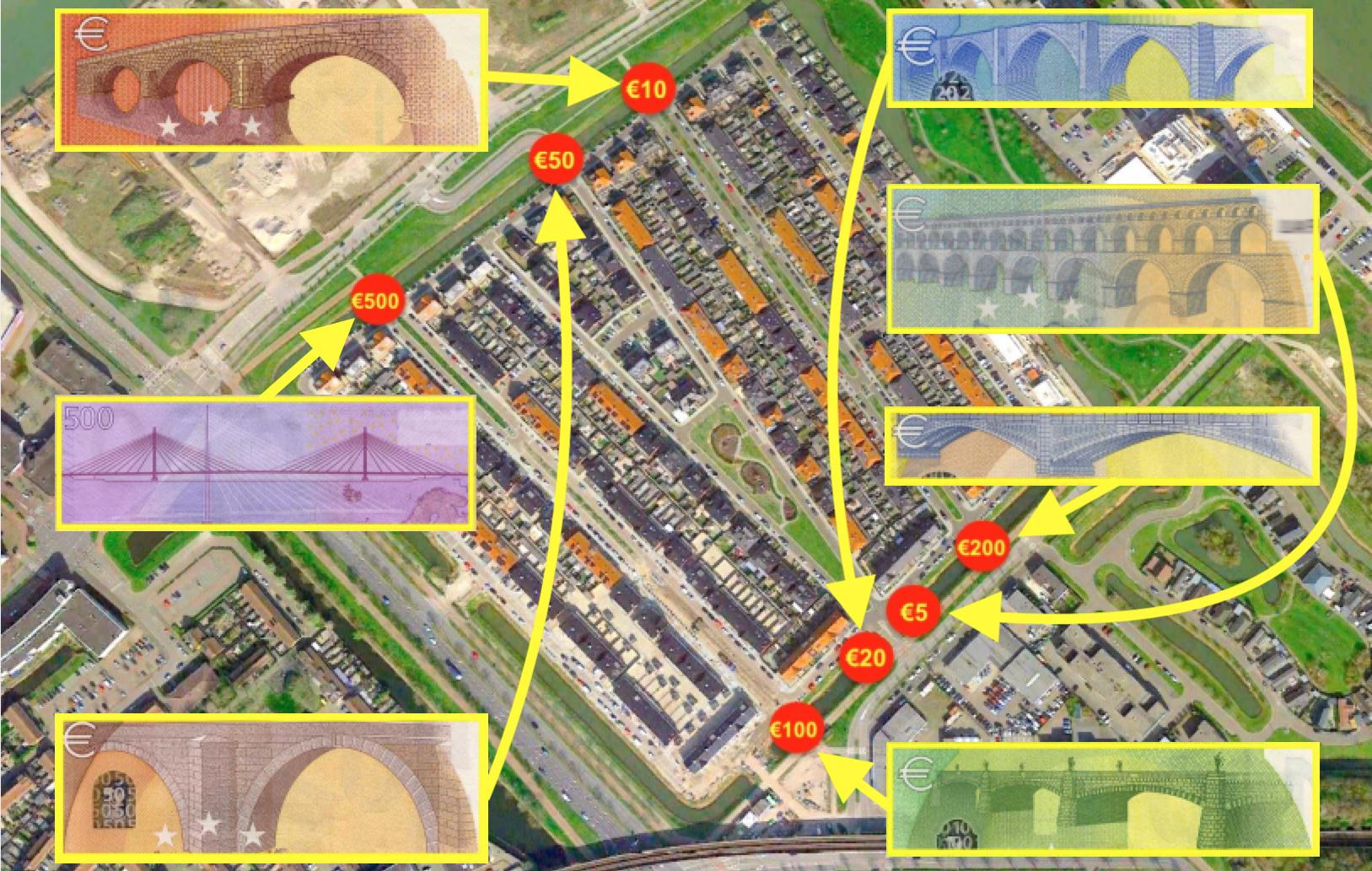

This map is a late example of an early type of tourist map, the so-called Rheinpanorama. It depicts, in overlapping sections, and embellished with postcard-like images of riverside attractions, the most popular stretch of what came to be known as the Romantic Rhine, from Bonn to Mainz.

The lovingly detailed and beautifully illustrated foldout sections of this Rheinpanorama were bound in book-form and published in 1909. By then, this particular genre was almost a century old. The first Rheinpanorama was published in 1811 by Elisabeth von Adlerflycht, who used continuous parallel projection to lend a bird’s-eye perspective to the course of the Rhine. The map proved a hit with the leisure traveller of the day, and really took off when steam ships started plying their trade on the Rhine about a decade later.

Its elongated sections are reminiscent of the perpendicular perspective of a few historical antecedents, such as the Tabula Peutingeriana, a Roman road map; and John Ogilby’s scroll maps, vertically detailing itineraries to and from London (see #405). A later example of this kind of riverine cartography are Harold Fisk’s alluvial maps of the Mississippi Valley (see #208).

As an unfolding tapestry of the Rhenish landscape, the Rheinpanorama maps are a visual delight. They are at once a lure towards, a guide to, and a souvenir of a river steeped in history, and shrouded in legend. They can be ‘read’ in either an upstream or a downstream direction. This first section starts at Cologne, nearest the river’s outlet into the North Sea at Rotterdam.

But for the giant twin spires of its famous Dom, Cologne looks tiny on the map-crowning panorama. On the bird’s-eye section below, Germany’s western metropolis looks positively rustic. Yet records show that the city’s population broke the half-million mark around 1910, right about when this map was published. Depicting Cologne as a middling city must have fitted with the general conceit of the map: to present the Rhine valley as a semi-rural idyll.

On the left bank of the second section, we see Bonn – in the second half of the 20th century the capital of West Germany, but at the time of printing still best known as Beethoven Town. The meticulous detail allows us a view of the tree-lined avenue leading towards the botanical garden, west of the tiny city centre. Further south, we find the Ruine Godesberg – the first of many castle ruins – and the Rolandsbogen, the first of many relics connected to medieval legends. On the right bank are Königswinter, in later years the location of many international conferences [2], and the Drachenfels (‘Dragon Rock’), where Siegfried, the hero of the Nibelungenlied, is supposed to have slain a dragon and then bathed in its blood, to become invulnerable.

This fair bit of river country shows a pleasing mix of islands (both complemented with what look like churches), towns (see how picturesque Linz and Honnef appear in the city views on the right), churches and castles. In a bend of the Rhine near Birgel, on the western shore, a towboat is transporting four barges upstream. Full of tourists, no doubt.

America is never far off in Germany. The small town of Andernach, on the left bank, was to become the birthplace of Charles Bukowski (1920-1994), the poet laureate of American B-literature. The town of Hammerstein, on the other bank, resonates as the surname of the great American songwriter Oscar Hammerstein (1895-1960).

Across from Festung (i.e. Fort) Ehrenbreitstein lies the city of Koblenz (rendered as Coblenz in old German spelling), still bearing the name, albeit bastardised, of the Roman settlement of Confluentes (‘where the rivers meet’). At that confluence, called Deutsches Eck (‘German Corner’), still stands the monument to Kaiser Wilhelm I. The giant bronze’s history is that of modern Germany in a nutshell. The equestrian statue celebrating German unification was installed in 1897, the horse’s behind pointing towards France is a symbolic snub of Germany’s archenemy. The statue was destroyed in 1945, after which its empty base became a symbol of Germany’s lost unity. A replica of the original statue was installed in 1992, after the collapse of communism had once again created a unified German state.

More picturesque ruins and towns in this section, but also, at the very bottom (right), a pictorial reference to the Lurley Felsen (actually shown on the next section). The Lurley, in modern spelling usually rendered as Lorelei, is perhaps the most famous natural phenomenon on the Rhine. A 120-metre-high rock, it marks the narrowest part of the river between Switzerland and Rotterdam. Dangerous currents have caused many accidents over the centuries, and thus contributed to the rock’s unavoidably infamous reputation. That in turn generated stories, poems and songs of enchanted maidens, enchanting sirens, and gnarly dwarves living in the very rock.

A septuplet of river rocks is named die sieben Jungfrauen, after the story that they are seven lovelorn maidens whose enchantment can only be broken by a prince. A bit further upriver, the town of Bacharach points echoes the name of another American songwriter. On the right bank, a picture shows a statue of Blücher, Germany’s Wellington (and some would say even more instrumental in defeating Napoleon at Waterloo).

Plenty of architecture to admire – ruined and otherwise – in this section of the river: postcards of Ruine Sonneck, Ruine Rheinstein, the Mäuseturm (‘Mouse Tower’ – medieval legend, anyone?), the Rochuskapelle, the Ruine Ehrenfels, Assmannshausen, and Ruedesheim, a National-Denkmal (‘National Monument’ in Niederwald, also, and equally bombastically, commemorating German unity) and the Schloss Johannisberg.

The postcards on the last plate show Bingen, the Dom and City Hall in Mainz, as well as statuary celebrating Schiller and Gutenberg. Also: Schloss Biebrich, and the town and Schloss of (French-sounding) Eltville. The river is rich in wooded islets, one of which – Hattenheim – is connected to the right bank via no less than five bridges. On the east bank, we find the fantastically-named town of Freiweinheim (‘the Home of Free Wine’), and see the moated and turreted town of Mainz, connected by bridge to the castle of Kastel.

A cityview of Mainz concludes the Rheinpanorama, with a Mississippi-esque steamboat plying the waters. The cityscape seems pretty detailed, suggesting accuracy, but the boat’s chimneys are too high for the bridge that it just passed. Maybe tourist maps share this trait with advertising: they look too good to be true.

This series of Rhine panorama maps found here on Wikimedia. A brief summary on the genre here on German Wikipedia; the article links to a few other examples.

Strange Maps #528

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] The hotels named Bristol that mushroomed across Europe (including, it might be added, in Britain itself, and across the world), were not part of an early multinational hospitality chain, but presumably all aimed at the same confidence-inspiring effect that the name of that British city had on the traveller. No satisfactory explanation has been provided why this should be so. One theory holds that Bristol as a port city was an obvious point of reference for British overseas travellers. Another states that it refers to the high standards demanded by the fourth Earl of Bristol of his lodgings while travelling across Europe. A third proposes that the name is conveniently short, and easy to pronounce in most languages. The heyday of the Hotel Bristol was the early 20th century. Today, over a hundred remain, across the globe. There’s even one in… Bristol itself.

[2] including the Afghanistan Conference of 2001, choosing Hamid Karzai as the leader of a coalition of Afghan forces aiming to oust to the Taliban.