640 – A Lion in the Garden: How to Translate a Continent

Many things puzzled the British student, on exchange somewhere on the Continent: what people ate, how they dressed, why they drove on the right. But nothing more so than the local language, and especially the book that tried to teach it to him. “Look at this sentence: The lion is in the garden. When am I ever going to need that?”

In the wintry suburbia where he showed me that page, there were plenty of gardens. But the most vicious creature likely to roam there would have been a quarrelsome blackbird, or a disgruntled mole. His course book, of questionable practicality even then, has now been relegated definitively to the dustbin of philology by the handiwork of another British student.

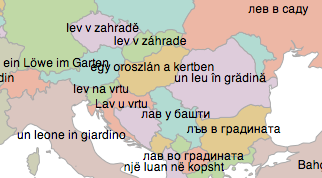

James Trimble, a computer science student at Glasgow University, has put together a map-based translation tool. Type in ‘a lion in the garden’, and the tool not only renders the answer in over 30 European languages, it also shows you exactly where you need to say what. In Ireland, at least in the Gaeltacht, you would run out into the street and warn your neighbours: leo sa ghairdin!. In Finland, you’d scream: leijona puutarhassa! (Poor cold lion, by the way). While in Turkey, you would need to yell: bahcede bir aslan!

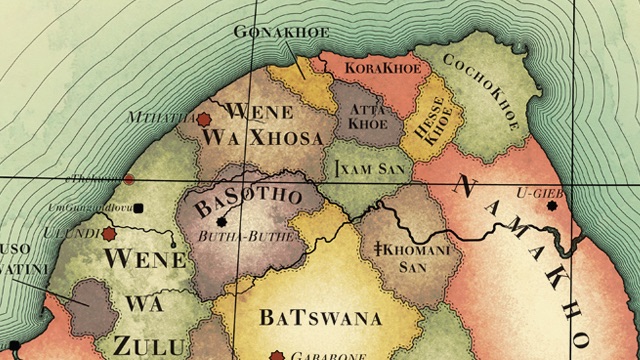

Mr. Trimble’s map nicely distinguishes between national and language borders. One translation – ein Löwe im Garten – suffices for the whole Germanosphere, which includes not just Germany itself, but also Austria and most of Switzerland. Belgium gets no translation of its own: in its northern half, you’re supposed to yell een leeuw in de tuin! (As you are in the Netherlands), while in the southern half, you’d have to get your tongue round the slightly more suave-sounding un lion dans le jardin, as you would in France. The Iberian peninsula is populated not just by Spanish (un leon en el jardin) and Portuguese(um leao no jardim), but also by Catalan (un lleo al jardi), Galician (un leon no xardin) and the totally unrelated, almost Hawaiian-sounding Basque (lorategian lehoia).

The language clusters are interesting: the Slavic languages all have lev or close variants of it for ‘lion’, but differ on what to call the garden: sadu in Russian and other eastern Slavic languages, ogrodzie in Polish, zahrade in both Czech and Slovak, and an interesting split in the former Yugoslavia: The Slovenian and Croatian garden is a vrtu, the Serbo-Croatioan one a bashtu,and the Macedonian onea gradinata (Bulgarian and Romanian use the same word). The isolate languages live up to their reputation: who but a Maltese would know for sure whether iljun or fil-gnien is the lion? Neither can anyone but a Magyarophone make (lion’s) heads nor tails of egy oroszlan a kertben.

Mr. Trimble’s European Translator is a clever combination of existing technology; in fact, he was prompted by the cucumber map, shown on this blog a few posts earlier, to send it in. The similarities are obvious. Also with what could be called the grandaddy of this type of comparative linguistic mapping, the Europa Polyglotta mapshowing the Lord’s prayer in the different European languages. But what makes the European Translator so irresistible is the tiny tweak that allows you to try out your own combinations and lay them out over the entire continent.

Mr. Trimble himself notes the limitations of the Google translator incorporated in his tool: “The expresion as snug as a bug in a rug translates to as snug as an error in a rug.” But that’s part of the fun. A tip: if you’re unsure of any particular language, mouse over it and its name will appear.

The European Translator can be found here. Many thanks to James Trimble for sending it in. Congratulations on your impending wedding, by the way, James. Or as they say in Lithuania: sveikiname!