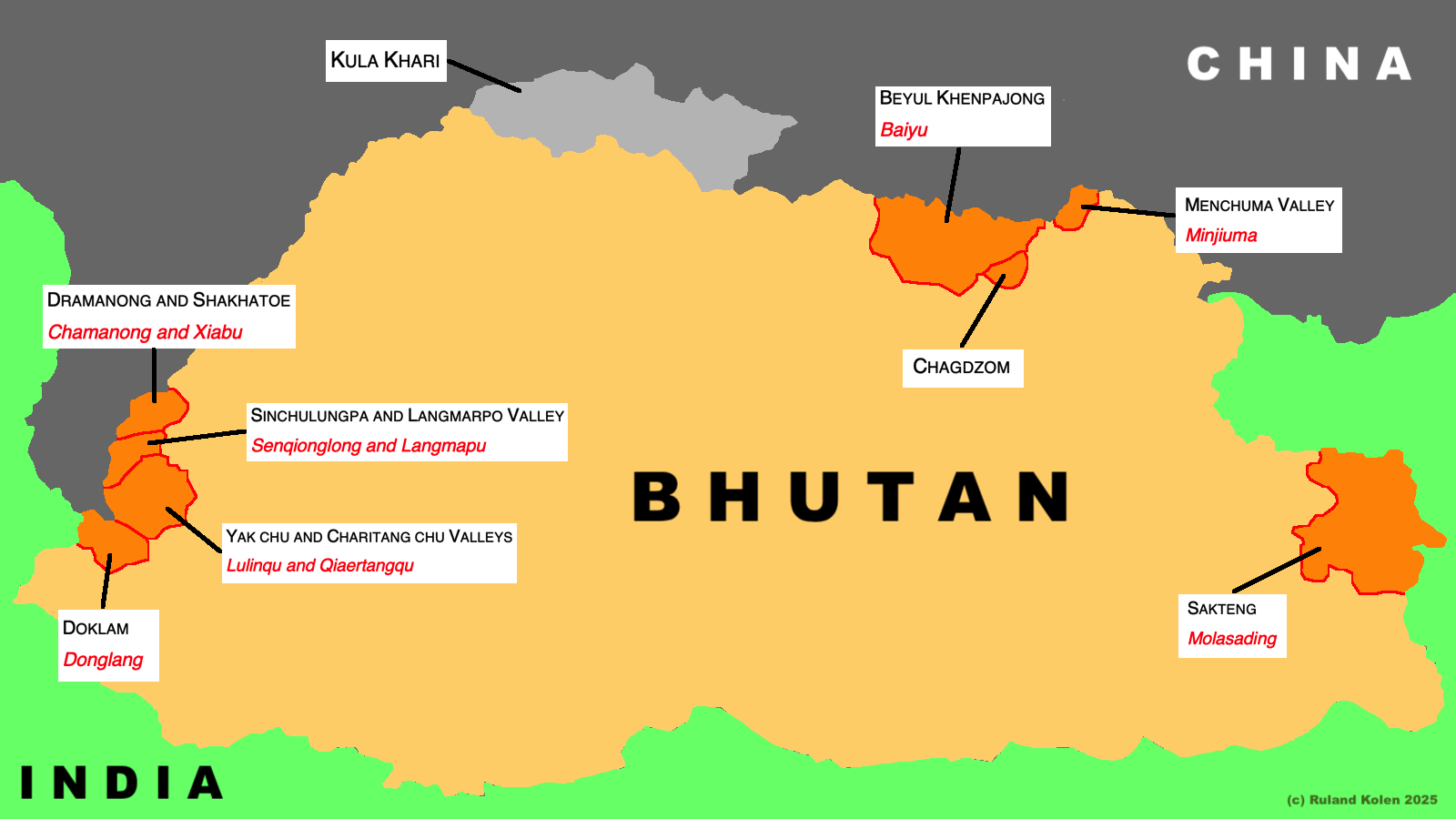

645 – Kiev Burning: a Map of the Front Line

This just in from Ukraine: President Yanukovych has sacked the country’s armed forces chief, has agreed a ‘truce’ with the three main opposition leaders, and wants to start ‘negotiations’ to end the bloodshed in the capital Kiev, which has claimed at least 26 lives in the past few days.

It’s a fork-in-the-road moment for Ukraine. Either political discourse takes over from street violence, or the country descends into full-blown civil war. Perhaps we’re already past that point of no return. In response to the latest violent attacks on pro-EU protesters, the western Ukrainian city of Lvov has announced its secession from the rest of the country; and the EU will decide on sanctions against Ukraine later this week.

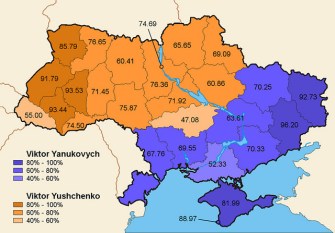

Then again, Ukraine’s political future has been a neverending toss-up ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992. The country is torn between its historical ties, cultural affiliations and economic links to Russia on the one hand, and the European Union on the other. That split is not just historical, cultural and economic – it is also geographic: the north and west of Ukraine is generally pro-EU; the east and south is more favourable to Russia. The current crisis is but the latest emanation of that rift (discussed earlier in #343).

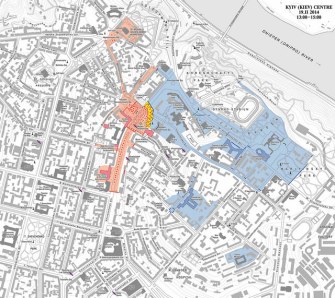

In a violent miniature of that nationwide divide, the streets of Kiev are now the battleground between the two camps. As with many other protests over the past few years, the opposition has rallied in the capital’s main square (see also Taksim in Istanbul, Tahrir in Cairo, etc.)

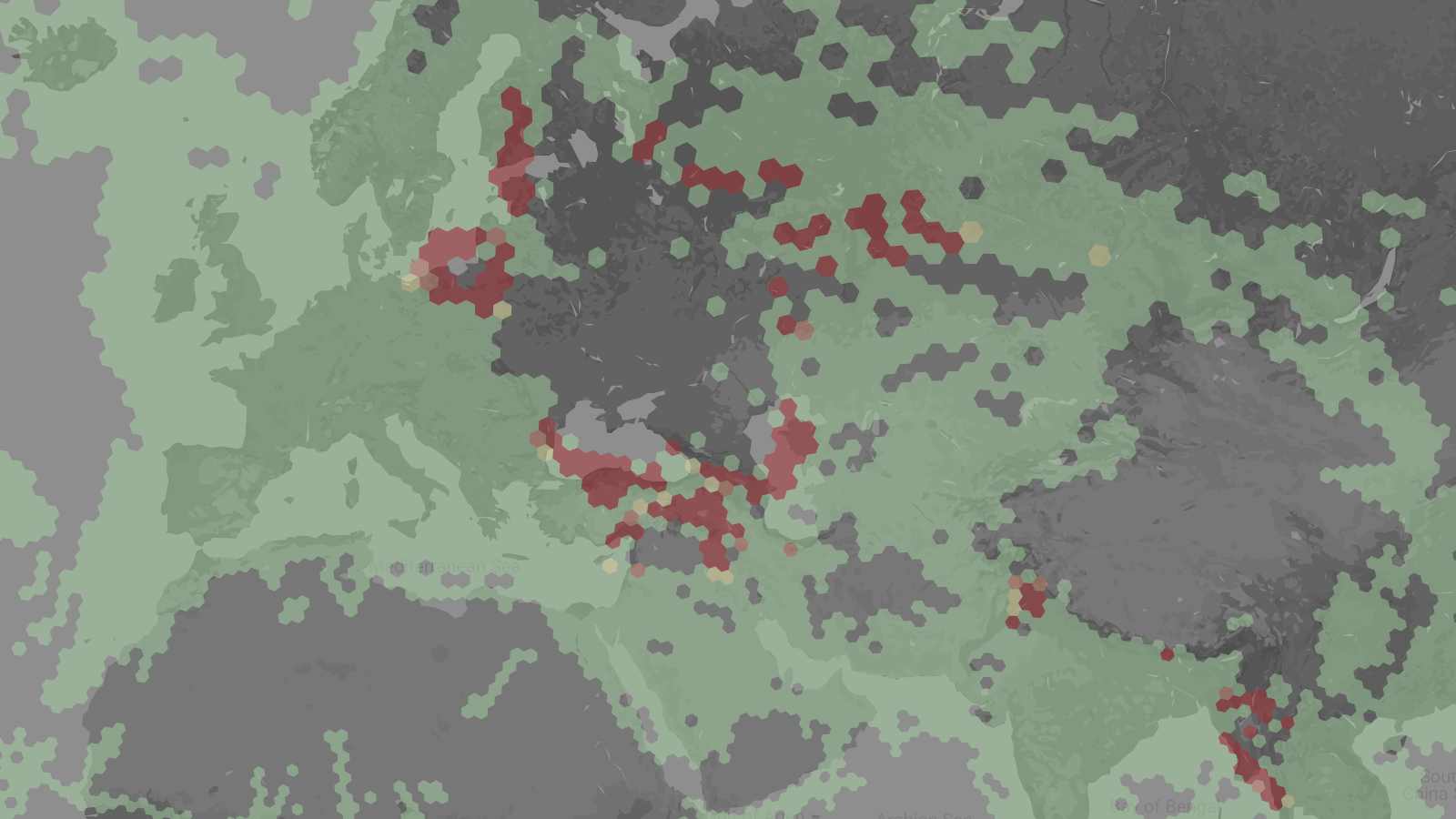

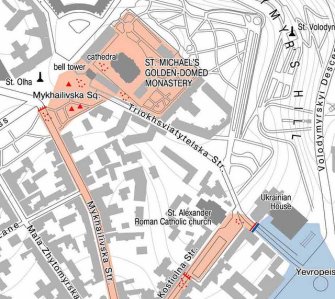

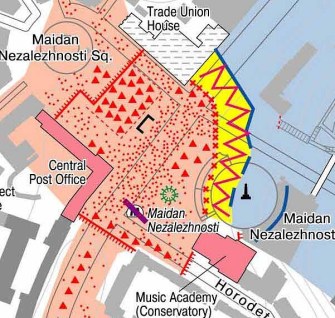

This is a snapshot of the situation on 19 February. The opposition, in red, controls most of Maidan Square, and three corridors: one to the north, along Mykhailivska Street, towards Mykhailivska Square and the golden-domed monastery and cathedral of St.-Michael’s.

A southern corridor, along Khreshchatyk Street, leads all the way up to the City Council and City State Administration building, occupied by the protesters. The nearby Khreshchatyk metro station is closed.

Another corridor, jutting to the northeast, leads up to St. Alexander Roman Catholic church and Ukrainian House. Red dots and red triangles presumably indicate concentrations and encampments of protesters. Red, spiked lines must denote protesters’ barricades.

The Yanukovych government, in blue, maintains a firm grip on the core district of the capital: barricading off the protester-held areas at the southern end of Maidan Square and near Ukrainian House, it retains control of the National Bank, the National Government building (Cabinet of Ministers), the Parliament building and the Mariinsky Palace, the official residence of the President.

Part of the area held by government forces, including the Parliament and Presidential Palace.

Two separate islands of blue – both heavily defended by government forces – are the Presidential Administration building, on Bankova Street, and the Interior Ministry, further south.

Will blue eat red, or red chase out blue? And will either lead to the unification of the country, or its break-up? Or will Kiev become a divided capital like Belfast or Nicosia, mirroring the schizophrenic nature of the country as a whole?

It’s still a toss-up. And since neither the EU nor Russia seems eager to intervene, the only bit of good news is that it’s still up to Ukrainians themselves to make heads or tails of their situation.

Many thanks to Leszek for sending in this map, found here on Livejournal.