65 – “Eastland, Our Land”: Dutch Dreams of Expansion at Germany’s Expense

In the Netherlands straight after World War II, there existed plans both official and unofficial to annex a large area of Germany as a way of obtaining war reparations (plans not to be confused with the more fanciful, pre-war plans described in posting #50 on this blog, which were used by the Nazis to scare the Germans into fighting to the bitter end).

Pivotal figure in most annexation schemes was Frits Bakker-Schut, a member of the State Commission for the Study ofAnnexation (Staatscommissie ter Bestudering van het Annexatievraagstuk – SBA) and secretary of the (non-governmental) Dutch Comittee for Territorial Enlargement (Nederlandsch Comité voor Gebiedsuitbreiding – NCG).

The SBA’s target immediately after the war was to create momentum within the Netherlands for annexation of German territory. In brochures, it proposed the so-called Wezergrens (’Weser Border’, after the river). The slogan was: Nederlands grens kome aan de Wezer (’Let the Dutch Border Reach the Weser’).

The NCG’s task was to study in specific task forces the feasibility of the plan. The mineral wealth, agricultural area and industrial potential for the intended areas were meticulously charted. The NCG presented its conclusion to the Dutch government at the end of 1945. It became known as the Bakker-Schut-Plan, and proposed three formulas for annexation:

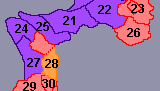

Plan A: Annexation of all areas west of the line Wilhelmshaven-Osnabrück-Hamm-Wesel-Cologne-Aachen (including all those cities).

Plan B: Basically the same proposal, but excluding the densely populated areas around Neuss, Mönchengladbach and Cologne from annexation.

Plan C: The smallest proposed area of annexation, with the border being moved to a line beginning in Varel, including all of Emsland and the Wesel area down towards Krefeld.

Apparently the plans included moves to ’de-Germanise’ the area, among other measures by giving towns a Dutch version of their German name. Some proposed place name changes (German name – Dutch name):

Jülich – Gulik

Emmerich – Emmerik

Selfkant – Zelfkant

Kleve – Kleef

Aachen – Aken

Bad Bentheim – Neder-Benthem

Emlichheim – Emmelkamp

Geilenkirchen – Geelkerken

Geldern – Gelderen

Goch – Gogh

Moers – Meurs

Münster – Munster

Neuenhaus – Nieuwenhuis

Nordhorn – Noordhoorn

Osnabrück – Osnabrugge

Veldhausen – Veldhuizen

Wesel – Wezel

Hoch- Elten – Hoog Elten

Jemgum – Jemmingen

Köln – Keulen

Mönchen-Gladbach – Monniken-Glaabbeek

Zwillbrock – Zwilbroek

Another measure to ’Dutchify’ the annexed area was to be population transfers (a bit like in the German areas to the east, which were annexed to Poland, Chzechoslovakia and the Soviet Union). In the folder Oostland – Ons Land (’Eastland – Our Land’), the NCG proposed to expell all people from towns larger than 2.500 inhabitants, all former members of the Nazi party and related organisations, and everybody who had settled in the area after 1933. The rest of the indigenous Germans would have the option of Dutch citizenship – if they spoke plattdeutsch (the local dialect, somewhat closer to Dutch than standard German) and had no close relatives in the rest of Germany. Everybody else was liable to be expelled without receiving compensation.

The Allied High Commission opposed the Dutch annexation plans on the grounds that Germany was already straining to accomodate 14 million refugees from the East. More refugees from the West could destabilise further a situation urgently needing consolidation, to counter the growing Soviet threat on Western Europe. Interestingly, there was also a strong opposition to the plans within the Netherlands, particularly from the churches.

Nevertheless, at the Conference of the Western Occupying Powers of Germany in London (from January 14 to February 25, 1947), the Netherlands officially requested the annexation of 1.840 km² of German territory. This area, a modified and smaller version of the aforementioned Plan C, included the isle of Borkum, the county of Bentheim and a strip of border territory close to the cities of Ahaus, Rees, Kleve, Erkelenz, Geilenkirchen and Heinsberg. In 1946, the area housed about 160.000 people – over 90% German-speaking.The concluding statements of the Germany Conference in London on April 23, 1949, awarded only very small fragments of German territory to the Netherlands – about 20 fragments, typically smaller than 1km² and totalling no more than 69 km².

Most of these were returned to Germany in 1963 and 2002. In fact, the ambitious Dutch annexation plans of 1945 have resulted in only one formerly German area now still under Dutch control: a small area called Wylerberg (in German; Duivelsberg in Dutch) close to the Dutch border city of Nijmegen, measuring no more than 125 hectares. I don’t know whether Mr Bakker-Schut is still alive, but if he is, he must be very, very disappointed…

This map, showing Plans A, B and C, retrieved from This page of the German Wikipedia.