Yes, All Roads Do Lead to Rome

All roads lead to Rome. So goes the saying. By which is meant, usually, that there are many different ways of reaching a certain goal. In that spirit, the saying itself has various applications. First and foremost, as a reminder of the value of lateral thinking. But also as the repository of an historical truth. Roads were indeed an essential instrument in the expansion and maintenance of the Roman Empire.

At its height, the empire controlled nearly 2 million sq. mi (about 5 million sq. km) of territory, stretching from Hadrian’s Wall in northern Britain to the estuary of the Euphrates on the Persian Gulf. Tying it all together was an extensive network of Roman roads, the nexus of which were the 29 major military highways that radiated from Rome to the far ends of the empire. Add another 350 great highways and many more smaller byways, and the network comprised 250,000 miles (400,000 km) of roads, 50,000 miles (80,000 km) of which were paved.

Many Roman roads survived the empire. Some even live on today, disguised as modern thoroughfares yet still recognisable by their straight course. London’s Oxford Street once was part of the Via Trinobantina. In Belgium and northern France, a number of straight roads of ancient lineage are nicknamed chaussées Brunehaut, after Brunhilda of Austrasia, the sixth-century Visigothic queen-regent who had several Roman roads repaired. In southern France, part of the Route nationale 7 follows the Via Agrippa.

Even after the fall of the empire, Rome remained a world capital, albeit of a more spiritual nature, drawing in pilgrims from all corners of Christendom. That attraction, combined with what remained of the imperial roads, must have given rise to the saying, first recorded by Alain de Lille in his Liber Parabolarum (1175): “Mille viae ducunt homines per saecula Romam” (“A thousand roads lead men forever to Rome”). Geoffrey Chaucer was the first to use an English version in his Treatise on the Astrolabe (1391): “Right as diverse pathes leden the folk the righte wey to Rome”.

In Antiquity, those roads were said to converge on the Milliarium Aureum, the Golden Milestone. Inaugurated in 20 BC by the Emperor Augustus near the Temple of Saturn, the Golden Milestone was considered the beginning of all roads leading out of Rome, and distances to cities across the empire were measured from it. On the Forum today, some marble remains are still labelled ‘Milliarium Aureum.’ Experts consider it unlikely that the remains are genuine. The exact location of the Milestone is uncertain, but it was close to the Umbilicus Urbis Romae (“Navel of Rome”), the symbolic centre of the city.

Similar zero distance markers existed in other ancient cities, e.g., Constantinople (fragments of the Milion resurfaced during excavations in 1960s Istanbul, near the Aya Sophia). The mysterious London Stone, visible behind a protective grille set in the facade of 111 Cannon Street, is reputed to have been the milliarium for Roman Britain.

Over 30 countries presently have official “kilometre zero” points. France’s is marked by an inscription in the square in front of the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. Egypt’s is located in the Post Office in Cairo’s Attaba Square. The U.S. has a Zero Milestone, located in President’s Park, just south of the White House. However, its official use is limited to distances in the District of Columbia.

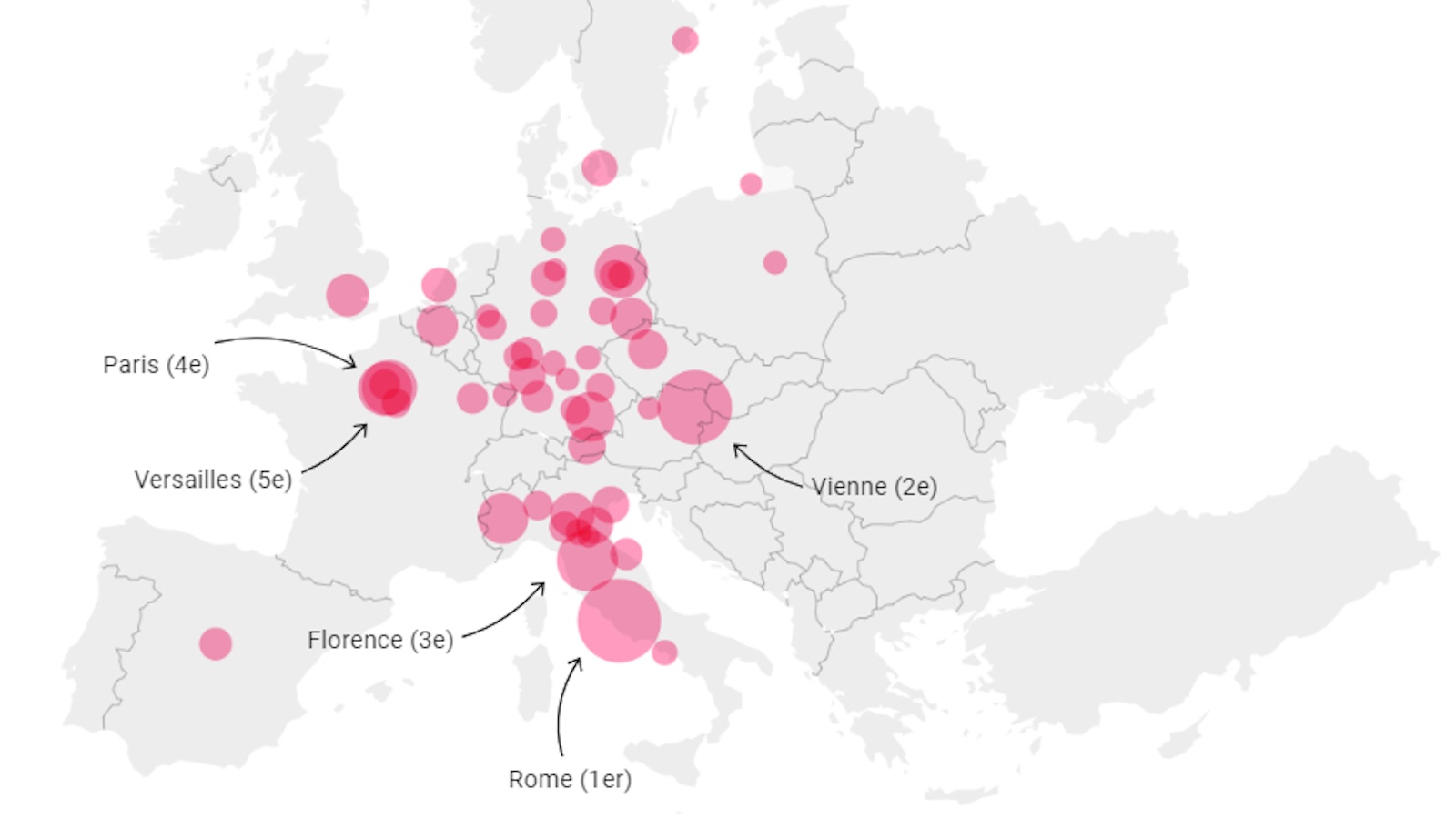

This road map goes beyond any Roman emperor’s wildest dreams. Selected from currently existing European roads, it shows what looks like the veins of a leaf, a nervous system, or a drainage basin, with the lines converging on Rome. The map was produced by German designers Benedikt Gross, Philipp Schmitt, and Raphael Reimann from Moovel Labs, a Stuttgart-based creative collective. Using data from OpenStreet Map, the designers used an algorithm to connect 486,713 starting points of roads to the Italian capital. It took the computer five hours to calculate all routes. The routes that are used more often are marked with thicker lines.

Seen from the Eternal City, those tentacles have an almost purposeful sense of direction: One shadows the Mediterranean on its way to the Iberian Peninsula; another is aimed straight for London and the British Isles; a third heads almost due north, branching in two at Hamburg. The main road east divides in three, one heading northeast to the Baltics and Russia; the other aimed at Ukraine; the third flowing through Istanbul before it fans out across Asia Minor.

Pleased with the result, the Moovel designers re-did the experiment, this time using as points of convergence 10 cities and towns in the U.S. that also bear the name Rome. The tiny hamlet of Rome, Iowa, suddenly becomes the capital of an empire bigger than the original Rome’s, dominating most of the western United States, controlling virtually the entire Pacific coast. Not bad for a town of 118 inhabitants, less than half the number it had in the year 1900. What monuments will now rise on the banks of the Skunk River!

Rome, Wisconsin, controls the northern quarter of the American West, but this transatlantic Carthage is no match for Rome-on-the-Skunk. Nor are the smaller Romes scattered throughout the country’s eastern half. Curiously, two Romes seem to have been built almost on top of each other. There only seems to be a trace of one Rome in the area, in Georgia. What’s going on there?

“Following the thought of shortest travel times from any given location, the next step of our mobility quest leads to the capital city of each state in the USA,” the researchers write on their project page. “What territory does each capital cover by shortest travel time? What is the place most remote place to the state capital?” That sounds and looks awfully familiar. Perhaps unwittingly, the designers have come upon something very closely resembling the Voronoi approach to mapping, where each area contains all points closer to its capital than to any other capital. Compare this map to the one produced by Jason Davies, data visualiser and voroniste extraordinaire.

The last map produced by the Moovel team replaces Antiquity’s one Rome with modern Europe’s many capitals. Here, too, notice the similarity with the Voronoi diagram. As it turns out, all roads do lead to Rome. It just depends on what your definition of “Rome” is.

Many thanks to Teemu Lahtinen and Xavier Bézu for pointing out the Moovel maps, found here on the Moovel website. Jason Davies’ map found here on his website. See also #657 for more on Voronoi maps.

Strange Maps #754

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.