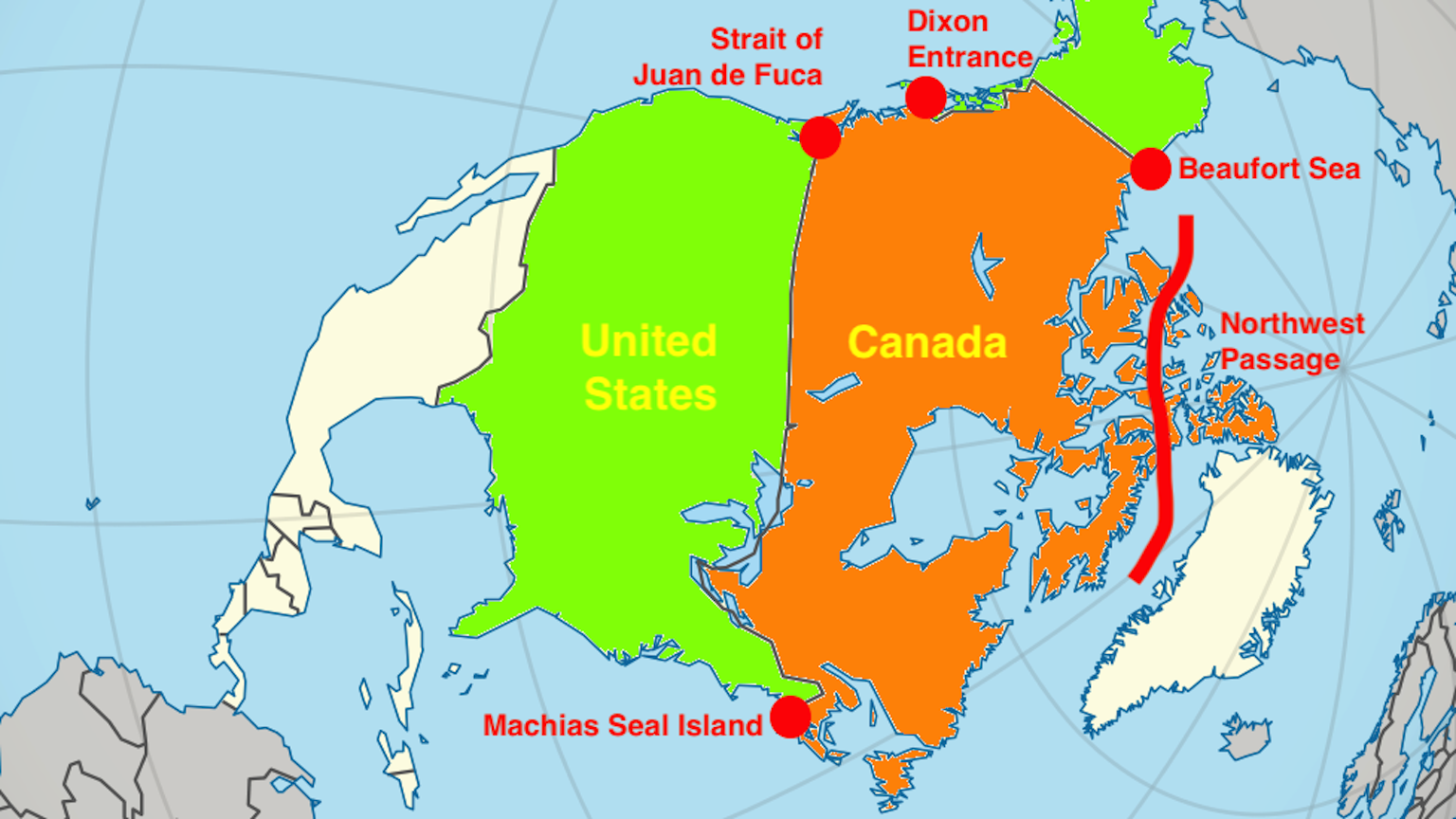

An astronaut’s view reveals China’s geopolitical claustrophobia

- This upside-down map of China is easily worth a thousand words.

- Its unfamiliar perspective provides context for China’s geopolitical anxieties and goals.

- It also shows history rhyming: A similar map from the 1940s focuses on Japan as the bogeyman.

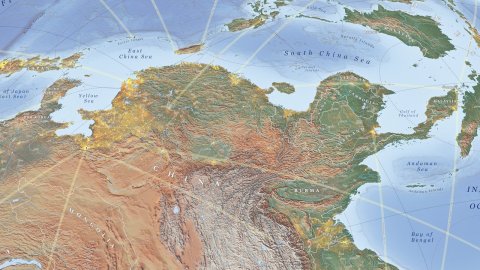

This map takes you to dizzying heights. It gives you the perspective of an astronaut in a space station circling the globe, hundreds of miles above the Eurasian land mass. You’re still crossing Central Asia, but already the Pacific Ocean glistens into view.

While you might be familiar with East Asia’s coastal contours from looking at world maps, you’re now seeing them upside down. You see the archipelagos — Japan, the Philippines, and Indonesia — strung out like a pearl necklace.

East Asia as seen from Eurasia

In the top right, there’s the unmissable bulk of Borneo, the world’s third-largest island (after Greenland and New Guinea, the western tip of which is just coming into view on the horizon). At the bottom right is Sri Lanka, the Indian subcontinent’s exclamation point.

East Asia is framed by two peninsulas: the Korean one, dismally divided between North and South, and the Malay one, shared more peaceably by Myanmar, Thailand, and Malaysia.

In between are two bulges. There’s the Indochina bulge, where Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia meet. The title of this map is “East Asia and the Pacific seen from Eurasia,” but its actual subject is the other bulge at the center of the map: China.

And its actual point is not to make you feel like you’re floating far above the earth (though that is a pleasant side effect), but rather to give you another perspective on this part of its surface.

If, as they say, an image is worth a thousand words, this map easily replaces a lengthy essay on China’s geopolitical situation, explaining some of the friction with its East Asian neighbors (and by extension, the U.S.)

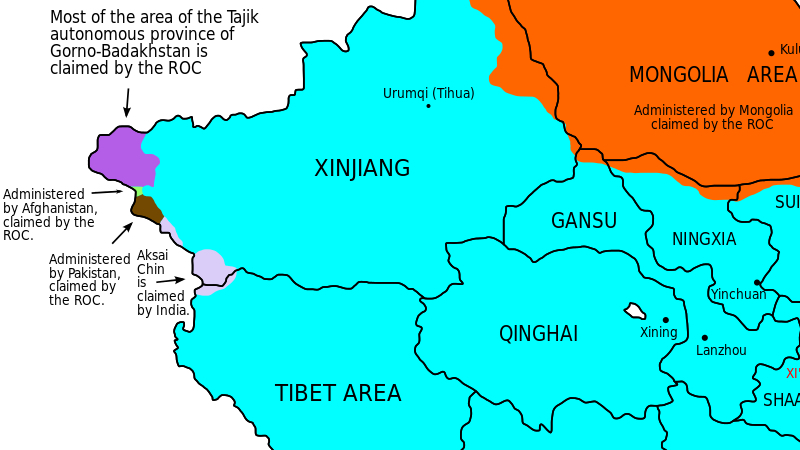

The map’s unfamiliar angle highlights China’s geographic constraints and points toward its strategic ambitions. China extends far into the Eurasian heartland. It holds the Tibetan Plateau, the world’s largest natural fortress. Tibet’s citadel-like qualities are the reason Beijing will never let go of this region. Just imagine another power — India, Russia, or the U.S. — commanding those heights.

They would literally look down upon China’s population centers, highlighted in yellow, most of which are close to the coast. Tibet is a wall protecting them from the outside, but it also seals them off from easy overland traffic and trade with India and other parts of Asia. For commerce, despite all the talk about Silk Roads old and new, China needs the sea.

But as the perspective of this map clearly shows, the Middle Kingdom looks toward the Pacific and feels like a decidedly “squeezed middle.” At its back: those isolating Himalayas. On its shore: hostile, American-allied powers, including Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines.

Island-grabbing in the South China Sea

Seen in this light, China’s island-grabbing in the South China Sea, much to the chagrin of other countries with overlapping claims, is clearly an attempt to secure the shipping lanes toward the Strait of Malacca. Even so, that narrow passage between the Malay peninsula and Indonesia’s Sumatra island remains outside of Chinese control, and can still be easily closed by other powers.

Closer to China’s home bulge is Taiwan, the Chinese island province where the defeated nationalist side in China’s civil war went solo after the communist takeover of the mainland in 1949. The tilted perspective of this map really drives the extent to which a renegade Taiwan is an irksome doorstop to China.

Between Taiwan and Japan, the Ryukyu Islands are a smaller string of pearls. The U.S. has a major base on Okinawa, the largest of the islands. Meanwhile, China disputes Japanese control over the Senkaku islands, which form the section of the archipelago that is closest to Taiwan.

Thanks to its unusual point of view, this map is an excellent way to experience firsthand the geopolitical claustrophobia that animates much of China’s foreign policy strategy. The map was made by Rhodes Cartography, which offers a high-resolution version of the map that’s available to download for free.

“My appreciation for Richard Edes Harrison and my attempts to emulate some of his style are obvious,” says the mapmaker.

Pioneer of the unfamiliar map perspective

During and after World War II, Harrison produced maps and atlases that pioneered the use of unfamiliar angles and sweeping global viewpoints. One of his most popular maps was “One World, One War,” published in In March 1942, in Fortune magazine.

At a time when the U.S. had not yet entered the war in full force, the map showed how close the conflict actually was to America, making the point that the fight could and should not continue to be ignored.

By introducing spatial thinking about global political matters to a wide audience, Harrison helped put the “geo” into geopolitics — a discipline that itself is also subject to shifts in perspective.

A World War II-era Harrison map shares almost the same astronaut-like viewpoint on East Asia as this more recent one, but with a slight difference: The focus of that map is not the current East Asian bogeyman, but the former one — Japan.

Strange Maps #1213

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.