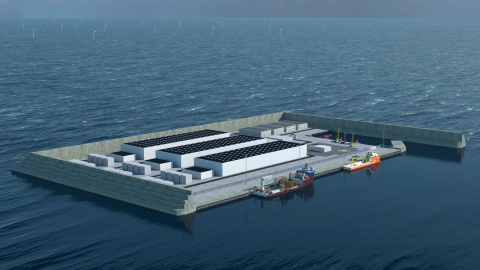

Is this Danish island soon coming to a coast near you?

Credit: Danish Energy Agency

- In 1991, Denmark constructed the world’s first offshore wind farm.

- Now they’re building an entire ‘Energy Island’ in the North Sea.

- As the U.S. catches up, Danish know-how could soon come to America.

Wind turbines of the Block Island Wind Farm, so far the only offshore wind project in operation in the U.S.Credit: Don Emmert/AFP via Getty Images

On Monday, President Biden designated a ‘Wind Energy Area’ in the waters between Long Island and New Jersey. It’s part of an ambitious plan to build giant wind farms along the East Coast. There’s currently only one offshore wind farm in the Eastern U.S., off Rhode Island (1).

When those wind farms get built, you can bet there’ll be Danish companies involved. In 1991, Denmark built Vindeby, the world’s first offshore wind farm. In the years since, Danish companies have maintained their global lead.

In February, the Danish government announced it would build the world’s first ‘Energy Island’. Everybody else in the world, take note: if the Danes pull this off, similar islands could soon pop up off your shores – perhaps also in the New York Bight.

So, what’s an Energy Island, and why does Denmark want one? For the answer, we spool back to June 2020, when a broad coalition of Danish parties, left and right, in government and opposition, concluded a Climate Agreement. This is Denmark’s plan not only to make a radical break with fossil fuels but also to show the rest of the world how it’s done.

Close-up of Energy Island, with two of the seawalls at the back and the port at the front. Credit: Danish Energy Agency

Due in large part to its pioneering work with wind energy, Denmark has a green image. But that hasn’t always reflected reality. Yes, in 2019 the country generated 30 percent of its energy from renewable sources – earning it 9th place worldwide (2). But in 2018, Denmark also was the EU’s leading oil producer (3).

Under the Climate Agreement, that will stop. Denmark will no longer explore and develop new oil and gas fields in its section of the North Sea. Extraction will be gradually reduced to zero. In exchange, Denmark will dramatically scale up the production of sustainable energy via offshore wind farms. The ultimate goal: nationwide carbon neutrality by 2050.

Offshore wind farms produce the bulk of Europe’s sustainable energy. And after a dip in the first decade of the century, offshore wind farms are on the rise again (4). One reason for the increased popularity: taller turbines, which means larger blades, which means greater capacity.

- In 2016, the tallest turbines were 540 ft (164 m) and had a capacity of 8 megawatts (MW).

- In 2021, turbines can be up to 720 ft (220 m) tall, generating up to 12 MW.

- Soon, the turbines will reach 820 ft (250 m) – not that much shorter than the Eiffel Tower (1,030 ft or 314 m, street to flagpole). These will have a capacity of up to 20 MW.

Potential position of Energy Island (red) off the western coast of Jutland, surrounded by a wind farm (green) filled with turbines (blue dots).Credit: Danish Energy Agency

As the shallow parts of the North Sea (<66 ft; <20 m) fill up with wind farms, the issue of managing the energy flow produced by these farms becomes acute. The obvious solution would be to build a central point where the energy is collected, converted from AC to DC and transmitted to one or more points onshore. Centralised management of the wind farms would mitigate the fluctuations in energy production and make it easier for supply to meet demand.

If supply is greater than demand, these collection points can also serve as storage units. Excess energy could be stored in batteries or transformed into hydrogen via electrolysis. If and when necessary, the hydrogen can then be transported onto land and reconverted into electricity.

The Dutch are thinking about it, and some have suggested the Dogger Bank as an ideal location: shallow and central within the North Sea, ideally placed to distribute energy to the various countries bordering the sea. But the Danes are doing it. The Climate Agreement envisaged not one, but two energy islands.

One would be Bornholm, Denmark’s Baltic island, halfway between Sweden and Poland, which would serve as the hub for local offshore wind farms. But the other would be an entirely new, entirely artificial island in the North Sea, to be built about 50 miles (80 km) off Thorsminde, on the western coast of Jutland.

Schematic overview of how an Energy Island could serve as a hub for collecting and redistributing sustainable energy.Credit: Danish Energy Agency

In February, the Danish government revealed how much this Energi-Ø would cost, how long it would take to build – and what it might look like.

- Energy Island will be built via the caisson method – essentially, sinking a watertight box to the bottom of the sea. The island will be protected from storms by high seawalls on three sides. The fourth side will feature a dock for ships.

- Construction could start in 2026 and is expected to take three years. Building the wind farms and transmission network will take a few years more. By 2033, it could be churning out its sustainable GWs.

- In its initial phase, the island will have an area of about 12 hectares (30 acres, or about 18 soccer fields). It will centralize the production of about 200 offshore wind turbines, with a joint capacity of 3 GW. That’s about the equivalent of 3 million households – slightly more than the total for Denmark.

- When fully completed, the island will have an area of around 46 hectares (114 acres, just under 70 soccer fields), collect the energy of 600 turbines, for a total capacity of 10 GW (5). That covers 10 million households.

- 10 GW is equivalent to about 150 percent of Denmark’s entire electricity needs (households, industry, infrastructure, etc.) That leaves plenty of scope for supplying neighbouring countries. Agreements have already been reached with Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium.

The plan also foresees a plant for hydrogen production on the island, either to be piped onshore, or stored and transported in large batteries.

Location of Energy Island (yellow) in the North Sea, showing potential connections towards neighboring countries.Credit: Danish Climate Ministry / Vimeo

In all, the island would cost DKK 210 billion (US$33 billion) to build – by far Denmark’s largest construction project (6).

The project will be undertaken in a public-private partnership between the Danish state and commercial interests. Because it is ‘critical infrastructure’, the state will retain a stake of at least 50.1 percent in the project. There are two scenarios for co-ownership:

- The island will be owned in its entirety by a company, in which the Danish state retains at least that smallest of majorities;

- Private companies will be able to own up to 49.9 percent of the island itself.

The Danish government needs private-sector input to overcome unknown and as yet untested aspects of the project, not just in terms of design and building an entire island from scratch, but also on how to operate and maintain it, and even when it comes to financing and risk management.

But where there’s risk, there is potential. If the project is successful, it will become the blueprint for similar energy islands the world over – and the companies that helped build the first one, will be in high demand to build the other ones too, perhaps soon in Biden’s ‘Wind Energy Area’.

Green, as the Danes have discovered, is not just the color of nature. It’s also the color of money.

Strange Maps #1077

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and on Facebook.

(1) Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind, a two-turbine pilot project 23 miles (43 km) off Virginia Beach, was completed last year.

(2) The Top 10 (2019) are Iceland (79%), Norway (66%), Brazil (45%), Sweden (42%), New Zealand (35%), Austria (38%), Switzerland (31%), Ecuador (30%), Denmark (30%) and Canada (28%).

(3) With 5.8 megatons of oil equivalent (Mtoe), Denmark beat Italy (4.7 Mtoe) and Romania (3.4 Mtoe). Oil production in the EU is on the way down. It peaked in 2004 (42.5 Mtoe) and has since halved (to 21.4 Mtoe in 2018). A similar trend has occurred in the two key non-EU oil producers in Europe. a. Norway’s oil production peaked in 2001 (159.2 Mtoe) and has since more than halved (to 74.5 Mtoe in 2018). b. The UK’s oil production peaked in 1999 (133.3 Mtoe) and has since been reduced by almost two thirds (to 49.3 Mtoe in 2018).

(4) The Global Wind Energy Council estimates that in 2020, a record 82.3 gigawatt (GW) of new wind power capacity was added, a 36% increase over 2019.

(5) The Bornholm energy hub is projected to top out at 2 GW.

(6) Inaugurated in 2000, the famous Øresund Bridge (Øresundsbroen), connecting Sweden to Denmark, cost about DKK 25 billion (US$4 billion) in today’s money. When it’s finished (by 2029, if work continues apace), the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link (18 km) between the Danish island of Lolland and the German island of Fehmarn, will be the world’s longest road/rail tunnel. It will have cost about DKK 55 billion (US$ 8.7 billion).