Four Forgotten Schemes to Straighten the Thames

I love dogs. Again: Isle of Dogs. A place so abject that it disguises its name as a declaration of affection to man’s best friend. Not to mention that its canine connection is tenuous at best, and that it wasn’t even an island for most of its history. Yet this forlorn corner of East London, famed mainly for its lack of distinction, could have been the focal point of Truly Great Things. If only Willey Reveley’s plan to straighten the Thames had come to fruition.

Alas, Reveley’s reputation mirrors that of the Isle of Dogs itself. Although an extremely ambitious architect, Reveley (1760-’99) is virtually forgotten nowadays – remembered only for the fact that most of his grand schemes came to nothing.

In 1790, he was commissioned by Jeremy Bentham, the great theorist of utilitarianism, to design and build the Panopticon – a prison policed by a single watchman, able to observe all inmates at all times while remaining unobserved himself. Although that concept has since proved inspirational for dystopias both literary (Hello, Big Brother!) and and actual (Hi there, NSA!), the prison as envisioned by Bentham and designed by Reveley was never built. Other large projects left unfinished by Reveley include an infirmary in Canterbury, and a public bath in, of all places, Bath.

But the architect’s most ambitious project was a design he unfolded three years before his death: a plan to force the Thames into a new, straightened channel between Rotherhithe and Greenwich. Eliminating one of the Thames’s largest meanders, which bounds the Isle of Dogs in the west, south and east, this would facilitate and simplify shipping up and down the Thames; and turn those obsolete river bends into giant wet docks for the ocean ships which were at that time clogging up the limited docking space.

As an added bonus, the river’s straightened channel would improve the outflow of the heavily polluted waters of the Thames, which then still served as the receptacle of London’s raw sewage – only after the Great Stink of 1858 would the government commission Joseph Bazalgette to build the sewerage system that is still largely in place today.

Reveley’s scheme, on the other hand, came to nothing. But the scant references to his plans do him the injustice of focusing to just one variant of his grand idea: the plan to cut through three peninsulas (at Rotherhithe, the Isle of Dogs and Greenwich), creating three new islands and as many wet docks. In fact, as these images from the British Library demonstrate, there were (at least) four different plans in circulation.

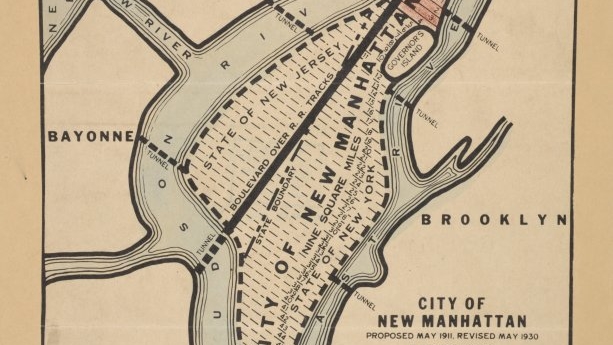

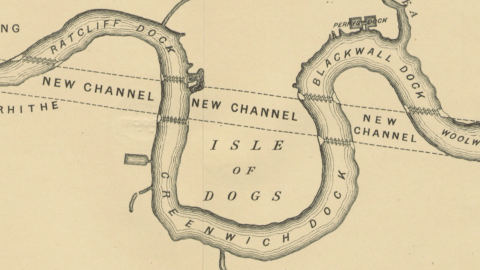

Plan No. 1 is the most modest of the four proposals, suggesting a new channel at the northern edge of the Isle of Dogs, completing its aquatic encirclement and thus validating its insular nomenclature. To accommodate that channel, and the uninhibited flow of Thames water, this plan also entails shaving off the tips of both Rotherhithe and Greenwich peninsulas. Locks would seal off the southern bend of the river, turning it into Greenwich Docks.

Under Plan No. 2, the channel would slant southward from the river’s bend at Rotherhithe, island-ifying not just the Isle of Dogs but also a much smaller North Greenwich Island (presently the location of the O2 Arena, formerly known as the Millennium Dome). Additional locks would create an extra wet dock, called Blackwall Dock.

Plan No. 3 is the most radical one, and perhaps this is why it is the best remembered (or least forgotten) of the four schemes, with the new channel slicing off a third island (Rotherhithe Island) and creating a third dock (Ratcliff Dock).

Finally, Plan No. 4 proposes two new channels, slicing off larger islands at Rotherhithe and Greenwich, but leaving the Isle of Dogs attached to the mainland (except by a narrow channel, if required). The result would be the elimination of Greenwich Dock, and two much more extended Ratcliffe and Blackwater Docks.

Only a few years later, but on a lesser scale than Reveley’s Plans 1 through 4, docks would slice off the Isle of Dogs from the mainland. The West India Docks, opened in 1802, and the East India Docks, opened in 1806, virtually cut off the Isle of Dogs from the rest of Poplar, and locks on its east and west sides eventually did turn it into a proper island.

The docks brought thousands of dockers and their families: the Isle of Dogs once had England’s highest concentration of council houses. After the closure of the docks from the 1960s onwards, unemployment and deprivation blighted the area. To highlight the area’s problems, the Isle of Dogs proclaimed itself an independent republic on 3 March 1970 – swiftly reabsorbed by Britain’s body politic.

Later, redevelopment of Canary Wharf created a new financial district, bringing opulence to the northern edge of the Isle of Dogs, in stark contrast to continuing deprivation elsewhere in the area.

But what of that curious name? The first mention of the Isle of Dogs goes back to 1520, but the origin of the name is lost in time. There are plenty of theories, though.

Some claim the island is named after Edward III’s greyhounds, others that its original name was Isle of Ducks, after the wildlife populating what was once known as Stepney Marsh, or the Blackwell Levels. Yet another theory is that the present name is a corruption of Isle of Dykes, which were built by Dutch engineers in the 17th century to reclaim the land lost in the catastrophic flood of 1488. Or it could just be a contemptuous reference to the dog’s life of anyone unlucky enough to reside in that inhospitable wasteland. In 1597, Ben Jonson and Thomas Nash wrote The Isle of Dogs, a play whose title unsubtly referred to England as a whole. The play was swiftly repressed for its ‘slanderous nature’, relegated to the obscurity suffered by Willey Reveley’s river-straightening schemes two centuries later.

Maps from The Thames and its Docks – a Lecture, With Plans, by Alexander Forrow. Original held and digitised by the British Library. Images in the public domain. Found here on Wikimedia Commons.

Strange Maps #699

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.