On tiny Hans Island, Denmark and Canada create world’s newest land border

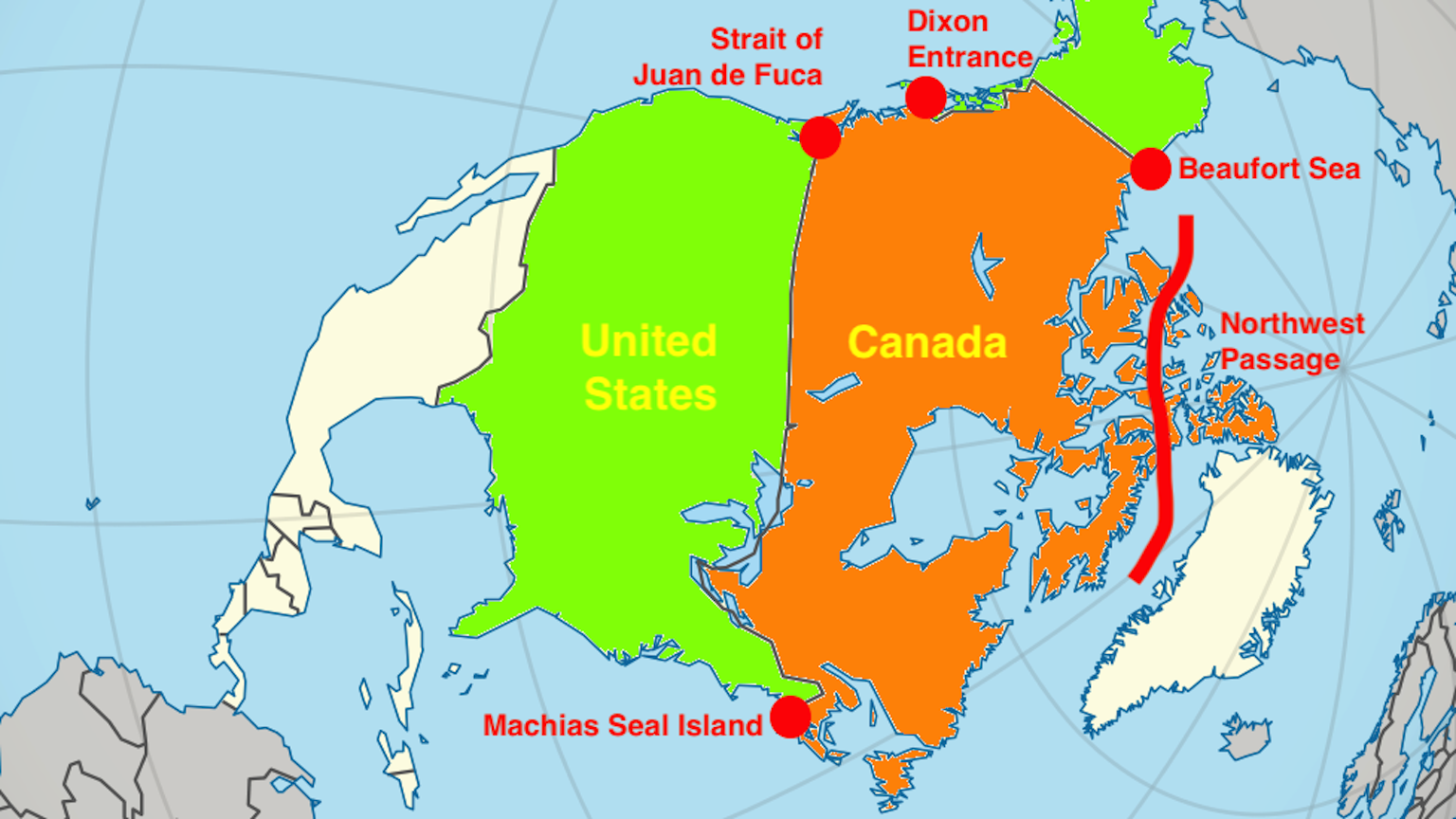

- For decades, Canada and Denmark disagreed over the ownership of Hans Island, between Greenland and Ellesmere Island.

- On June 13, 2022, both countries finally decided to split the island and define the rest of the disputed maritime border.

- The deal is a model for settling border disputes, but it ends one of history’s most charming border traditions.

Until June 13, Canada and Denmark belonged to the relatively small club of countries who share a land border with just one other country. In Canada’s case, it was the United States. Denmark’s only land neighbor was Germany.

Now that club is down two members (to 15), because Canada and Denmark have gained a land border — with each other. That may seem impossible, since both countries are separated by an ocean. But avid followers of obscure border disputes will know this has to do with Hans Island.

Hans Island, a.k.a. Tartupaluk

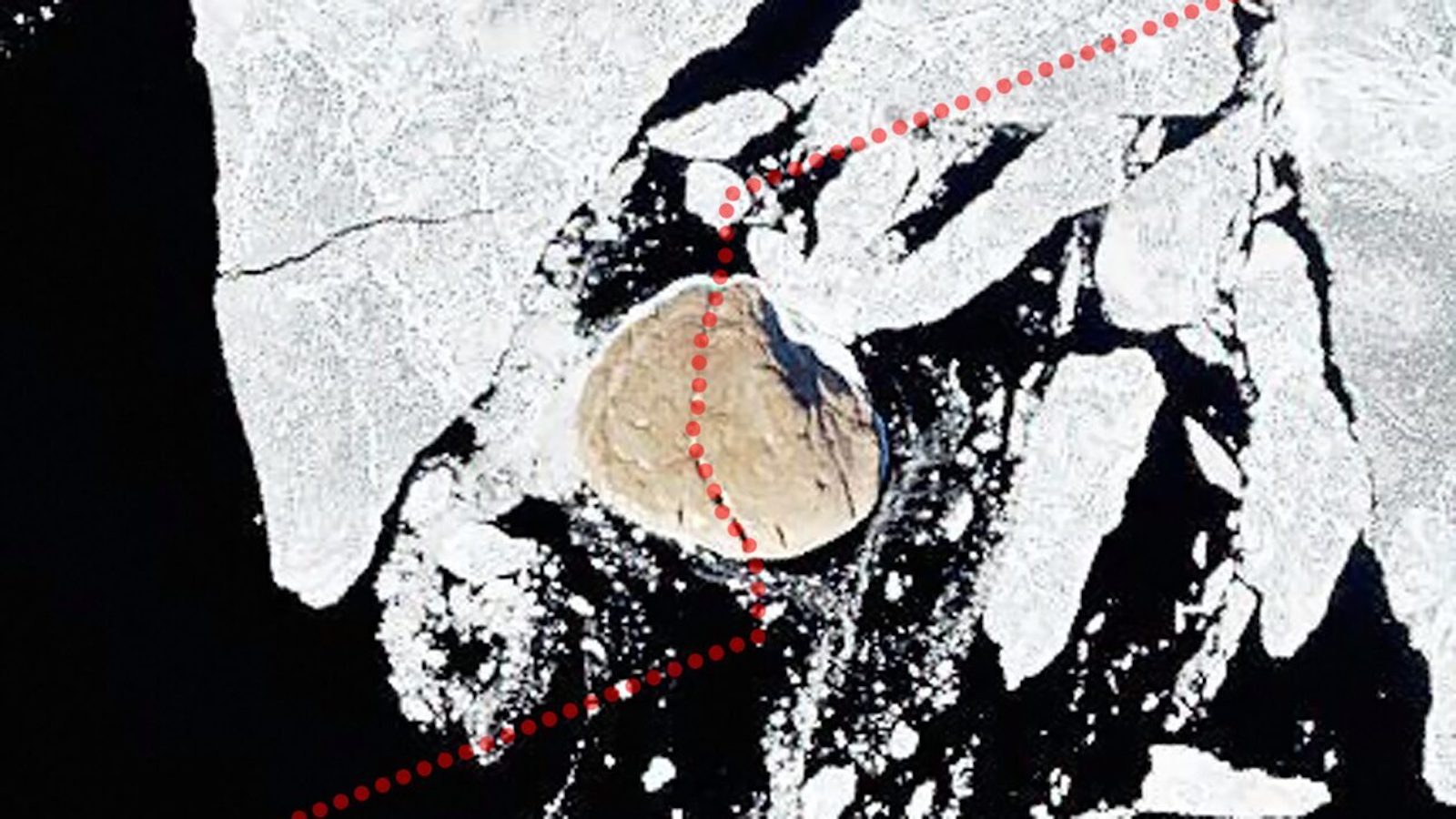

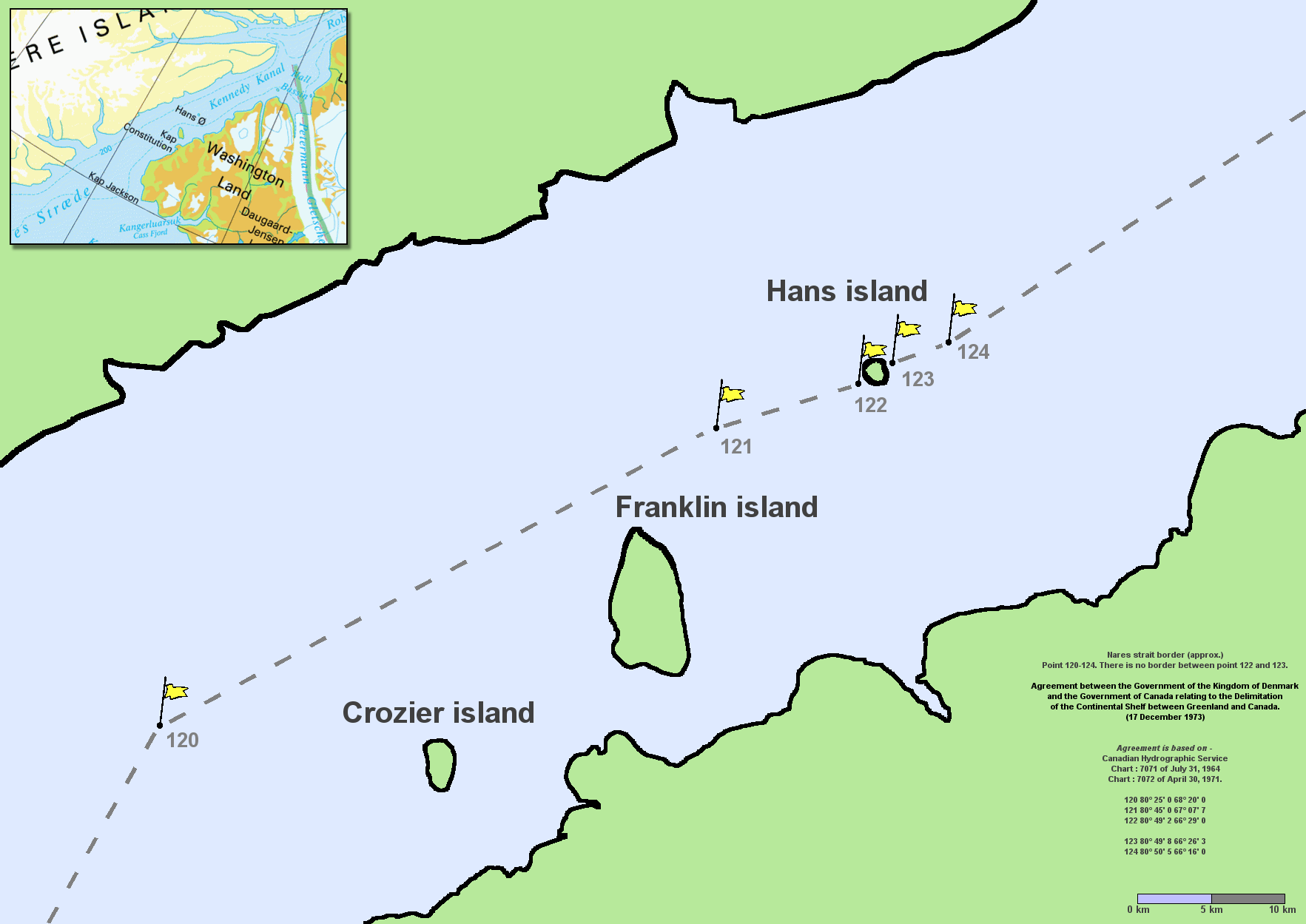

Known in the local Inuit languages as Tartupaluk (and in Danish as Hans Ø), Hans Island is a small (half a square mile, or 1.3 km2), barren, and uninhabited rock at 80° North, in the frigid waters of the Kennedy Channel, halfway between Ellesmere Island and Greenland.

Ellesmere Island is Canada’s northernmost island and part of Nunavut, the country’s newest territory (since 1999), where the indigenous Inuit exercise political autonomy. Greenland, for its part, is the world’s largest island, and (since 1979) an autonomous part of the Kingdom of Denmark. Despite the home rule in both Nunavut and Greenland, the respective national governments in Ottawa and Copenhagen remain competent when it comes to demarcating international borders.

The dispute over Hans Island emerged in the early 1970s, when Canada and Denmark agreed on most of their maritime border — the first ever drawn up with the help of a computer — with the notable exception of Hans Island, bang in the middle of the Kennedy Channel, which both claimed as their own.

Hans Island’s immediate value is as a hunting ground for locals. But possession of an island comes with rights to its territorial waters, as well as to the hydrocarbons and other potential riches beneath those waves — hence, the obstinacy exhibited by both the Canadian and Danish governments when it comes to the official deed to Hans Island.

Fighting the Liquor War

For nearly half a century, neither country would budge an inch. The overlapping claims even led to a conflict between both countries — although the so-called “Liquor War” must qualify as the most low-key and good-natured of international squabbles.

It all started in 1984, when Canadians left a Canadian flag and a bottle of Canada Club whisky on the island, as a way of marking Hans Island as their territory. The same year, a Danish minister reciprocated, leaving a Danish flag, a bottle of Gammel Dansk schnapps, and a message reading, “Welcome to the Danish island.” In the years since, visiting officials and military personnel of both sides have kept up the tradition, leaving behind a flag, a message, and a bottle of liquor for the other side.

As adorable as that is, the Arctic is heating up, literally and figuratively. As global warming advances, the region is becoming strategically more important. In that context, unresolved border disputes are as dangerously negligent as an unlocked back door.

In November 2021, both countries accelerated their long-standing plans to resolve the issue with marathon negotiations on neutral ground in Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. The agreement they published this June isn’t a condominium (i.e., joint ownership) as had been mooted before, but splits the island in two — not, however, by the straight line that cuts the Kennedy Channel in half (and that runs across the island), but by a line that follows a natural feature on the island.

The world’s newest land border is about 3/4 mile (1.2 km) long and mirrors a gorge that runs across the island from north to south. Additionally, the delegations from Denmark and Canada have ironed out small issues along the entire maritime border between them — at 2,412 miles (3,882 km) the longest maritime border in the world.

“A clear signal to the world”

As a result, the maritime territory of Greenland is growing with an area the size of Jutland, Funen, and Zealand combined, reports Danish news channel TV2. (Jutland is the Danish mainland, the bit attached to Germany; Funen and Zealand are two of Denmark’s biggest islands. Hans Island is helpfully compared to Sprogø, a tiny island in the Great Belt between Funen and Zealand.)

“This agreement sends a clear signal to the world, that border disputes can be resolved based on international law, and in a pragmatic and peaceful way, where all parties come out as winners,” says Jeppe Kofoed, Denmark’s Foreign Minister. And in case it wasn’t clear whom exactly this comment was directed at, he continues: “That is an important signal to send now that there is so much war and unrest in the world.”

Before it can take effect, the agreement must now be ratified by the Danish and Canadian parliaments, as well as those of Nunavut and Greenland.

Many thanks to Lasse Winther Wehner for sending in a link to the TV2 story.

Strange Maps #1154

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.