Russia’s embassies are being relocated to “Ukraine Street”

Credit: MapChart / Ruland Kolen

- One of the more peculiar ripple effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a slew of new addresses for many of its embassies.

- An online campaign aims to change dozens more Russian embassy addresses to reflect global condemnation of the war.

- Ukraine has already reciprocated, naming one (rather unimpressive) street after Boris Johnson, the British prime minister.

Diplomacy is the continuation of war by other means. Words are its main form of ammunition. And although these are usually lobbed at the enemy by ministers, envoys, and ambassadors, sometimes a humble street sign will do the trick.

That is the thinking behind Ukraine Street, a global campaign to rename the addresses of Russian embassies and consulates around the globe, turning those street names into messages of support for Ukraine and extreme annoyance for Russia’s corps diplomatique.

Symbolic gestures, clear signals

The online campaign collects signatures and targets dozens of capitals and other major cities worldwide, hoping to emulate several name changes that came about early in the conflict. Of course, renaming streets is a symbolic gesture that is unlikely to change any minds, either in those diplomatic missions or in Russia proper, but they do clearly signal what the host countries think of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

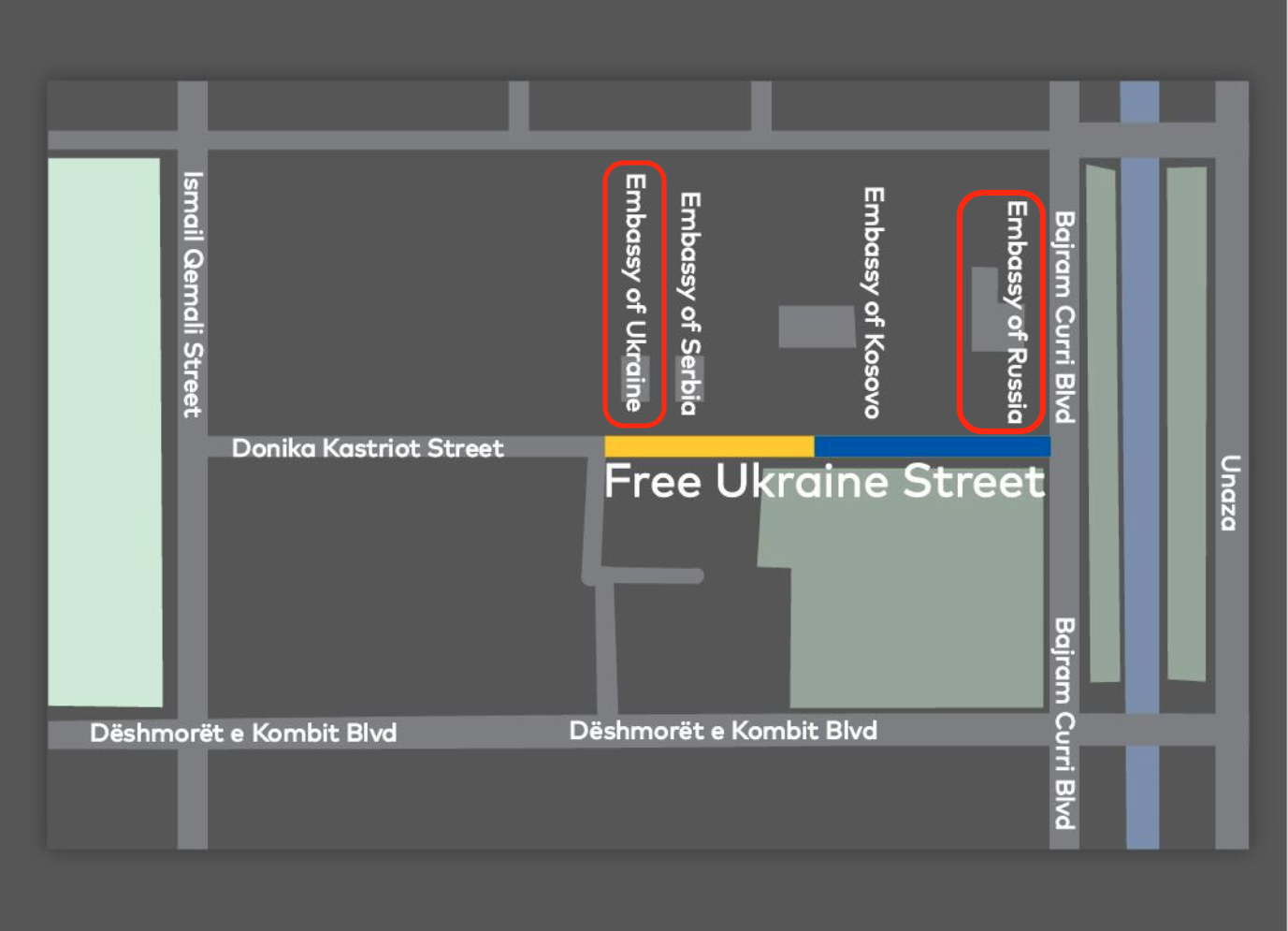

The first country to give the Russian embassy a new address was Albania. On March 7th, less than two weeks after the start of the war, part of Rruga Donika Kastrioti (Donika Kastriot Street) in the Albanian capital Tirana was officially renamed Rruga Ukraine e Lirë (Free Ukraine Street).

The new street is home to two potentially explosive diplomatic pairings, for it features not just the embassies of Russia and Ukraine, but also of Serbia and Kosovo.

On Radical Avenue, turn off at Compromise Street

The next day, it was Norway’s turn. The Norwegian and Ukrainian capitals have a special historical tie: Oslo was founded in the mid-11th century by Harald Hardrada, king of Norway (and claimant to the Danish and English throne), whose wife was princess Elisiv, daughter of Yaroslav the Wise, Grand Prince of Kiev.

The intersection that passes by the Russian embassy in Norway, located at Drammensveien 74 in Oslo, was officially renamed Ukrainas Plass (Ukraine Square). The local city council originally had entertained the more radical plan to rename the entirety of Drammensveien, a busy thoroughfare. Eventually, they settled on a compromise of simply renaming the area instead of the street — a decision that involves a new street sign but does not require the Russian embassy to get a new address.

On March 10th, two Baltic states took similar steps. In the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, the section of Latvių gatvė (Latvia Street) that runs by the Russian embassy was officially renamed Ukrainos Didvyrių gatvė (Ukrainian Heroes Street). “From now on, the business card of every employee of the Russian Embassy will have to pay tribute to Ukrainian heroes,” Remigijus Šimašius, the mayor of Vilnius, wrote on Facebook.

Boris Nemtsov Square

The street runs past Boriso Nemcovo skveras (Boris Nemtsov Square), an earlier slight to the Russians: Nemtsov is the Russian opposition politician who was gunned down in 2015 near (and allegedly on the orders of) the Kremlin.

On the same day, the Latvian capital Riga renamed the part of Antonijas iela (Antonijas Street) that passes by the Russian embassy Ukrainas neatkarības iela (Ukrainian Independence Street). On March 24th, the section of Korunovační (Coronation Street) in the Czech capital Prague that runs by the Russian embassy was officially renamed Ukrajinských hrdinů (Ukrainian Heroes Street).

In Prague, too, the area adjacent to the embassy had already been named Náměstí Borise Němcova (Boris Nemtsov Square). Washington, DC also has a Boris Nemtsov Square near the Russian embassy, but it as yet has no plans to “ukrainify” any other part of the surroundings.

Slava Ukraini

On April 27th, the square on the corner of Garðastræti and Túngata in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik, not at but near the Russian embassy, was officially named Kænugarður Torg* (Kiev Square). And on April 29th, the city council of Stockholm, the capital of Sweden, decided to name part of Marieberg Park, by the Russian embassy on Kungsholmen island, Fria Ukrainias Plats (Free Ukraine Square). The move follows a rejected proposal to name the road on which the embassy is located Zelenskyy Street.

It’s not just Russian embassies that face embarrassing addresses; the same goes for Russian consulates, too. In Canada, Toronto has unofficially renamed the part of St. Clair Avenue that runs past the Russian consulate “Free Ukraine Square.” In Poland, locations near Russian consulates-general have been renamed in Kraków (Free Ukraine Square) and Gdańsk (Plaza of Heroic Mariupol).

A few other places, not connected to embassies or consulates, have been renamed. For two weeks in April, the Spanish town of Fuentes de Andalucia changed its name to Ucraina, as a show of solidarity with Ukraine and a sign of protest against the Russian invasion.

Nevertheless, with the first shock of the war now over, and the novelty of news about fighting and dying in Ukraine wearing off, the drive to rename streets and squares near Russian embassies seems to be losing some momentum.

“No action too small”

In early March, the New York Times reported on an initiative to rename Kristianiagade (Kristiania Street) in Copenhagen, home to the Russian embassy in Denmark, to Ukrainegade (Ukraine Street).

That now seems off the table, according to local news sources, out of concern not to embarrass other inhabitants of the street and/or to preserve the unity of the street names in the Norge (Norway) area of town. (Kristiania is the former name of Oslo.) In the NYT article, Danish MP Jakob Ellemann-Jensen, who led the drive for the name change, said: “There is no action that is too small.” Apparently, there is.

Regardless, the “Ukraine Street” website keeps collecting signatures and suggesting name changes, using previous examples to prod local citizens and authorities into action.

The section of Bayswater Road adjacent to the Russian embassy in London should be renamed Ukraine Street, it suggests, because “(t)he UK has a great track record in solidarity with what is right. In the 1980s Glasgow’s St. George’s Place was renamed Nelson Mandela Place due to its position as the home of the Apartheid South African consulate,” the website mentions. “Let’s do it again for Ukraine!”

Ukraine is returning the favor. Since everything Russian is now unfashionable in Ukraine, the town council of Fontanka, east of Odessa, has decided to give Mayakovsky Street, named after a Russian poet, a new name. It is henceforth to be known as Boris Johnson Street, in recognition of the British prime minister’s extensive support for Ukraine.

It should be mentioned, though, that Vulytsya Borisa Dzhonsona (Boris Johnson Street) is nowhere near the British embassy, or any other remarkable location. It is a road of such minor importance that one wonders whether the good people of Fontanka are actually signalling that Johnson should be doing even more than he is doing at the moment.

Strange Maps #1147

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.

*Note: Kænugarður is an Icelandic adaptation of the Slavic Kijan-gorod, which literally means “Kyi’s castle.” Icelandic uses its own roots to represent the names of a number of foreign cities, giving these places the added attraction of an exotic, Viking-sounding toponym. They include: Vinarborg (Vienna, Austria), Algeirsborg (Algiers, Algeria), Peituborg (Poitiers, France), Stóðgarður (Stuttgart, Germany), Mexíkóborg (Mexico City, Mexico), Erilstífla (Amsterdam, Netherlands; little used), Hólmgarður (Novgorod, Russia), Góðrarvonarhöfði (Cape of Good Hope, South Africa), Mikligarður (Istanbul, Turkey; although mainly in a historical context), Kantaraborg (Canterbury, England), and Páfagarður (Vatican City).