The Cold War that Wasn’t: Norway Annexes Greenland

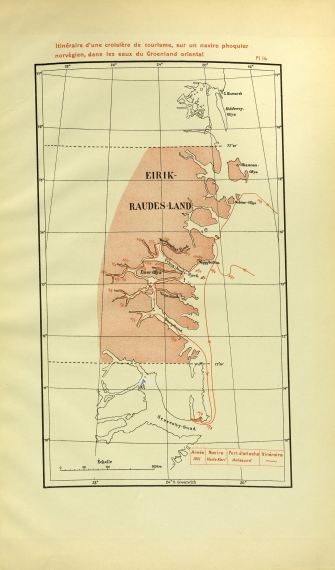

On 27 June 1931, five fishermen sent a historic telegram from Greenland to Oslo: “The Norwegian flag has been hoisted at Myggbukta […] We’ve called this Erik the Red’s Land.” Two weeks later, Norway officially proclaimed the annexation of Eastern Greenland. It could have been the start of a very Cold War indeed.

Had the Norwegian gambit succeeded, our world maps today would trace a border across Greenland’s pristinely white interior, separating the Norwegian territory of Eirik Raudes Land in the east from the Danish bulk of the island. Considering the hostile nature of Norway’s takeover, that border would perhaps be traced with barbed wire on the ground and marked by watchtowers — a frozen conflict not unlike the one manacling Pakistani and Indian troops to the deadly Siachen Glacier in northern Kashmir (see also #629).

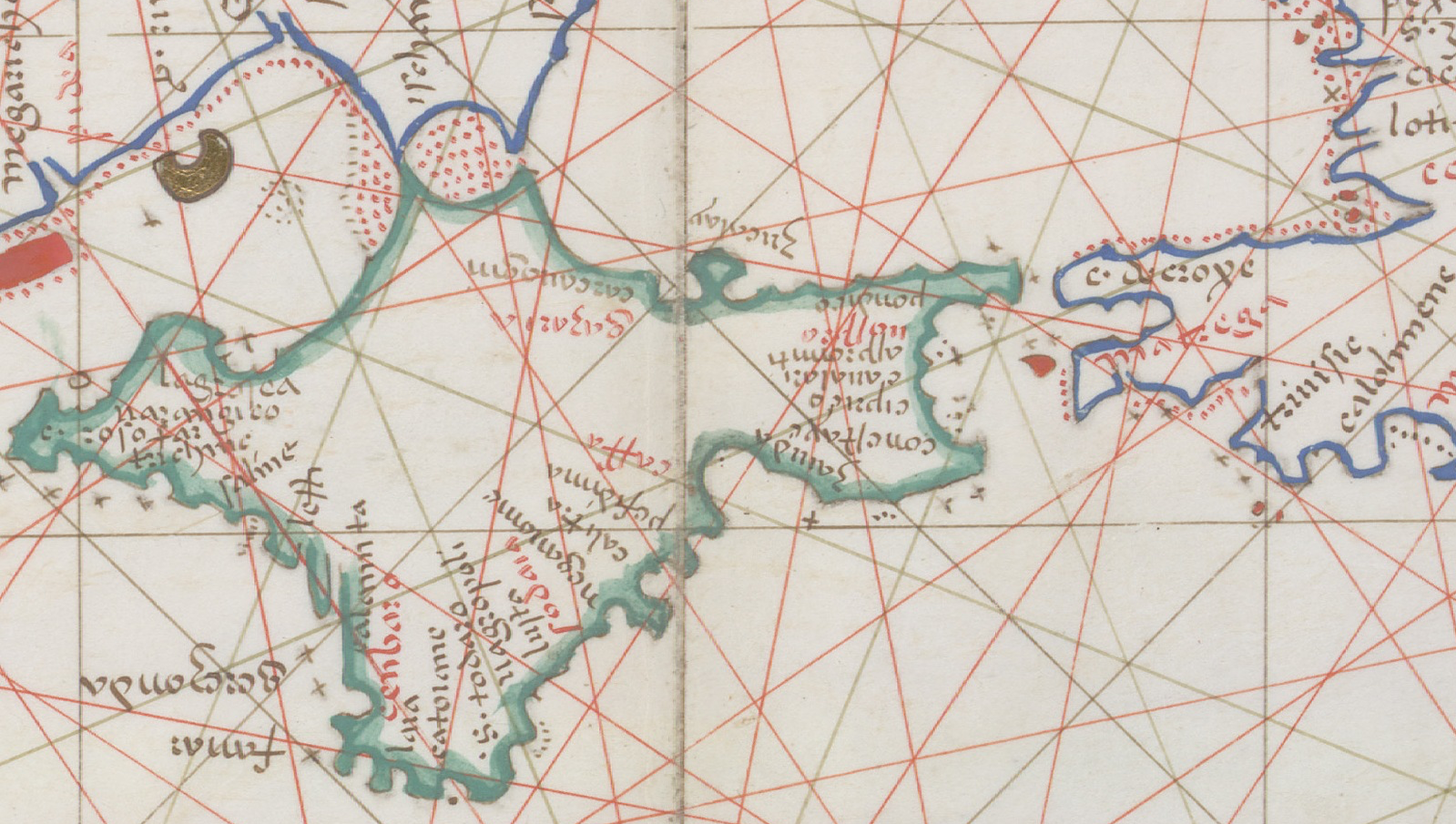

But there is no Norwegian colony on Greenland, and no map of Erik the Red’s Land — at least not a current one. Denmark and Norway brought their dispute before the International Court of Justice, which in 1933 ruled in favor of Copenhagen. Oslo meekly abided by the decision. This map dates to the brief interlude when Norway sought to bolster its claim to the Eastern Greenland by the two time-honored means at its disposal: occupation and cartography.

After the German occupation of Norway in 1940, the collaborating regime briefly re-occupied Erik the Red’s Land, threatening to bring the World War to Greenland’s inhospitable shores. But the shared suffering under the German occupation brought Danes and Norwegians together again. Past differences over Greenland were forgotten, as was the danger — very real at one time — that they would have gone to war over Greenland in the 1930s.

The Falklands War of 1982 between Argentina and the UK has been described as “two bald men fighting over a comb.” The colorful expression negates the fact that apart from national pride, rich fishing grounds were at stake, as was the possibility that the economic zone surrounding the islands was rich in hydrocarbon reserves.

Similarly, Norway had sound economic reasons to stake a claim on Greenland, or at least part of it. These were backed up by centuries of history — and a sense of frustration that the Danes had “stolen” Greenland from them.

Around the year 1000, Greenland was settled by Erik the Red and other Norse colonists from Iceland, who had themselves arrived from Scandinavia a few centuries earlier. These Greenlandic and Icelandic colonies formed a cultural and political continuum with the mainland, but those ties preceded the modern nation states that would later lay claim to them.

In the 1260s, the Norse Greenlanders recognized the overlordship of the Norwegian king. But by 1500, the Norse colonies had died out, and Norway had entered into a political union with Denmark, which would last until the early 19th century. This joint kingdom was dominated by Denmark, which took the lead when contact with Greenland was re-established in 1721, beginning with the missionary work of Hans Egede, the “Apostle of Greenland.”

The Treaty of Kiel, which in 1814 transferred Norway from Danish to Swedish rule, maintained the former Norwegian colonies of Greenland, Iceland, and the Faroe Island for Denmark. Norway, which would have to wait until 1905 before it gained full independence from Sweden, never recognized that treaty.

But things only came to a head in 1921, when the Danish parliament officially declared Greenland to be an integral part of Denmark. Henceforth, non-Danes had to ask for permission to go ashore on Greenland. Norwegian fishermen had a long tradition of whaling and sealing in the region, but the Danes did not consider that sufficient motivation to grant them access. Naturally, the Norwegians considered Denmark’s declaration of sovereignty a provocation, an attack on their economic interests in Eastern Greenland.

Hence the flag-raising incident at Myggbukta (in Danish: Myggebugten, in English: Mosquito Bay), where the telegram was sent from a pre-existing Norwegian radio station. The nationalist government in Oslo was sympathetic to the self-styled declaration of dependence by Hallvard Devold and his four fisherman friends, but dithered for two weeks before backing it up with a Royal Proclamation. On 10 July 1931, it informed the world that Norway was taking possession of the area in Eastern Greenland between Carlsberg Fjord in the south and Bessel Fjord in the north, extending from latitudes north 71”30′ to 75”40′.

The sense in Oslo’s government circles was that Norway was justified to force Denmark to share Greenland’s resources, especially by occupying parts of the island where the Danish, concentrated in the south and west of Greenland, were all but absent. But the fear was that this could lead to a war with Denmark, which Norway — smaller, weaker, poorer — would very probably lose. This did not deter Norway’s defense minister at the time from threatening to deploy the navy.

Meanwhile, Norway hastened to shore up its claim. The writer Idar Hangard wrote a pamphlet titled “Denmark’s False and Norway’s True Claim to Greenland,” attacking the unfair Treaty of Kiel. Norwegians built 76 houses in East Greenland, vastly outnumbering the two Danish huts in the area. Skirmishes between Danes and Norwegians became a frequent occurrence.

All of which sounds an awful lot like the right ingredients for a cold war that could have turned hot at any moment. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed, by bringing the conflict to the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

A procession of experts testified to who held a better claim to sovereignty over Greenland. They included famous Danish-Inuit explorer Knud Rasmussen, who had mapped parts of Eastern Greenland during his sixth and seventh Thule Expeditions from 1931 to 1933.

On 5 April 1933, the ICJ backed up Denmark’s claims to Greenland by 12 votes to two, validating the Treaty of Kiel and declaring Norway’s occupation in the east illegal. To this day, the ICJ verdict on Eastern Greenland remains the only time a territorial dispute in the Arctic was settled by international arbitration. Contemporary sources attribute the outcome at least partly to the interventions of the charismatic Rasmussen, who died shortly after the verdict.

Norway’s defeat also at least partly results from the indecision and division within Norway’s political elite. Just one illustration: When Norway’s Prime Minister Peder Kolstad died on 2 March 1932, he was succeeded by Jens Hundseid. However, Justice minister Asbjørn Lindboe missed the deceased PM’s guidance so much that he consulted a medium to obtain his advice.

In 1940, the defense minister who had threatened to use the Norwegian navy became the head of Norway’s collaborating regime. Vidkun Quisling — whose surname became synonymous with “traitor” — revived the rejected claim, extending it to the entire island. But the Nazis vetoed his plans for a military reconquista of Greenland.

Ironically, it wasn’t Norway, but Nazi Germany itself that established a presence in Eastern Greenland. From August 1942, the Germans installed a total of four manned weather stations in the area, on Sabine Island and Shannon Island among other locations. Skirmishes cost the lives of one Danish and one German soldier — the only combat fatalities of World War II on Greenland. The last German weather station, Edelweiss II, was seized by the Americans on 4 October 1944, its 19 German personnel captured without casualties.

Contemporary map of Eirik Raudes Land found here. Map showing location of Eirik Raudes Land on Greenland here from Wikimedia Commons. Both in the public domain. Full text of the ICJ verdict here. The Nazis also established a presence on the South Pole. See #88 for more on the ‘colony’ of Neuschwabenland.

Strange Maps #704

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.