The Blue Banana – the True Heart of Europe

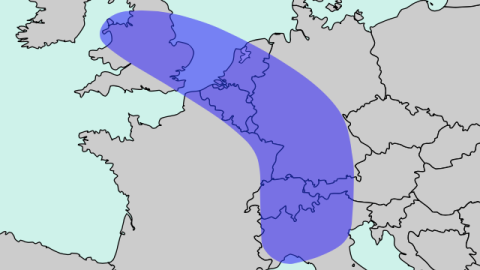

Few inhabitants of the world’s biggest megacity have any idea of its existence, or of its name. Stretching from Manchester to Milan, the Blue Banana is home to around 100 million people. This is the true Heart of Europe.

That heart is as movable and disputable as the definition of Europe itself. The geographic center of the European Union has been moving steadily eastward, as the political project has been expanding in that direction (see #498). Delimiting Europe’s civilizational core is as debatable as the declarations of ‘otherness’ that are used to define it (see #22).

More recently, cities and regions that have marketed themselves as the ‘Heart of Europe’ include places as far apart as Berlin and Brussels, the Czech Republic and Romania. But the true heart of Europe – looking at cold, hard economic and demographic data – has a much more definite circumscription, at least according to Roger Brunet, the French geographer who in 1989 revealed the existence of the Blue Banana.

That spatial concept described the until then nameless megalopolis straddling the European continent, stretching from the industrial cities in the northwest of England to their counterparts in the northern part of Italy, also including densely populated, highly industrialised areas in the Benelux countries, France, Germany and Switzerland.

The northern terminus of the Blue Banana is located around Manchester and Birmingham, takes in the densely populated southeast of England (including of course London), then jumps across the Channel to include a few high-density areas that already have collective names, such as the Randstad (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and other urban centers on the western edge of the Netherlands), the Flemish Diamond (Antwerp, Brussels, Ghent) and the Ruhr Metropolis (Dortmund, Düsseldorf, Cologne, etc.)

The Banana bends southwards along the Rhine, including Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Switzerland before reaching northern Italian powerhouses such as Milan, Turin and Genoa.Measuring between 1,500 and 1,700 kilometers between its northwestern and southeastern termini, the Blue Banana is home to between 90 and 110 million people (out of a total of 730 million for all of Europe).

It includes major seaports such as Rotterdam and Antwerp (#1 and #2 in Europe, both in the world top 20); airport hubs like Heathrow, Frankfurt and Schiphol (#3, #11 and #14 in the world); and the Hqs of the European Union, the European Parliament, the International Court of Justice, NATO and the European Central Bank.

In population size, it outnumbers the 85-million-strong Taiheiyo Belt, stretching from Tokyo to Fukuoka in Japan, and thus could be construed as the largest First World agglomeration in the world – the Ganges River agglomeration is greater, but is not as economically prominent as the Blue Banana. So, on a global level, Europe’s core zone can arguably said to comprise the world’s largest concentration of people, industry, money and economic power.

Brunet’s aim had been to delineate the economically most developed region within Europe, but the catchy name was not his invention. As he later reminisced, “The name was added by the media: the banana shape was pointed out at a press-conference by Jacques Chérèque, a government minister; the color was then given to it by an artist at the Nouvel Observateur, in an article by Josette Alia three days later which baptised the banane bleue.”

The color was later interpreted as a reference to the blue on the European flag, or to the blue collars of the factory workers’ uniforms. Spontaneous though it was, the term’s simplicity and memorability helped Brunet’s concept gain wide recognition. The ‘blue banana’ became popular currency among economists, europhiles, and other commentators – much more so than the region’s alternative names (Hot Banana, Bluemerang, European Backbone, Manchester-Milan Axis and others).

The Blue Banana is more than a geographer’s whim. It is the result of a beneficial set of circumstances, that include a temperate climate, fertile soil on the plains and a variety of mineral resources. Long processes such as the emergence of trade routes, improvements in agriculture, the development of industry and advancements in science culminated in the 19th century, when the region was a global powerhouse of industry, finance and science. Even though the Blue Banana, like much of the rest of the developed world, has now moved into a postindustrial phase, the region remains a major economic center.

Brunet’s definition of Europe’s economic core pointedly excluded Paris and other French conurbations, as a critique of French economic insularity. Brunet wanted his spatial concept to convince French authorities of the necessity of greater economic integration with the European core. According to Brunet, France had lost this connection to Europe’s economic heartland in the 17th century, when it expelled the Huguenots – a protestant sect with a penchant for doing business.

As a concept, the Blue Banana’s main asset is that it allows those involved to transcend the narrow national boundaries that, decades after the start of European integration, still define the mental space inhabited by most European citizens. The Blue Banana makes it easier to see Europe’s economic, demographic, cultural and political evolutions in a wider, regional framework.

But it is unlikely the Citizens of the Blue Banana will ever unite and rise up to fight for a common cause. Like other megalopolises, it is the favorite tool of planners and think tanks. Especially if they are French: the BosWash – America’s urban corridor, stretching from Boston over New York and Baltimore to Washington DC – is a term popularised in 1961 by Jean Gottman, another French geographer.

The Blue Banana, meanwhile, may have been doomed by its own success. The term proved so popular (again, mainly with planners and think tanks) that adjacent regions started to market themselves as part of the same spatial concept, thus diluting its strength – later models even included Paris, while the original point was to exclude the French capital.

Other regions have developed their own banana concept, including the Mediterranean arc (the so-called Golden Banana), the Scandinavian banana, the Alpine Furrow, etcetera. The opening up of Eastern Europe after the fall of Communism has exposed other corridors of economic dynamism, such as the Danube basin, or one stretching from Paris over Berlin to Warsaw.

Today, the Blue Banana model is no longer accurate: the former conurbations have grown several new branches, and the last few years have seen so much expansion that one might speak of a Blue Star — although the Blue Banana remains at its core. As it turns out, the Blue Banana is as moveable a feast as that Heart of Europe itself.

Image of the Blue Banana produced by Arnold Platon, licensed for reproduction under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, found here on Wikimedia Commons.

Strange Maps #695

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.