Hell or high water: The wonders and dangers of Earth’s tidal ranges

- The average global tidal range is about 1 m (3 ft), but local variance can be extreme — and dangerous.

- The Bay of Fundy has the world’s greatest difference between high and low tide: 16.5 m (53 ft).

- In places like these, the tide comes in faster than you can outrun it, leading to deadly tragedies.

A rising tide, in the phrase popularized by JFK, lifts all boats. It’s a vivid allegory for the president’s preferred path to general prosperity. But its sunny optimism hides a more sinister aspect of the ebb and flow of the open seas.

If you’re caught out on the foreshore of a place where the difference between low and high water is big enough to drown you — and you’re boatless and on foot — a rising tide can turn menacing, even deadly.

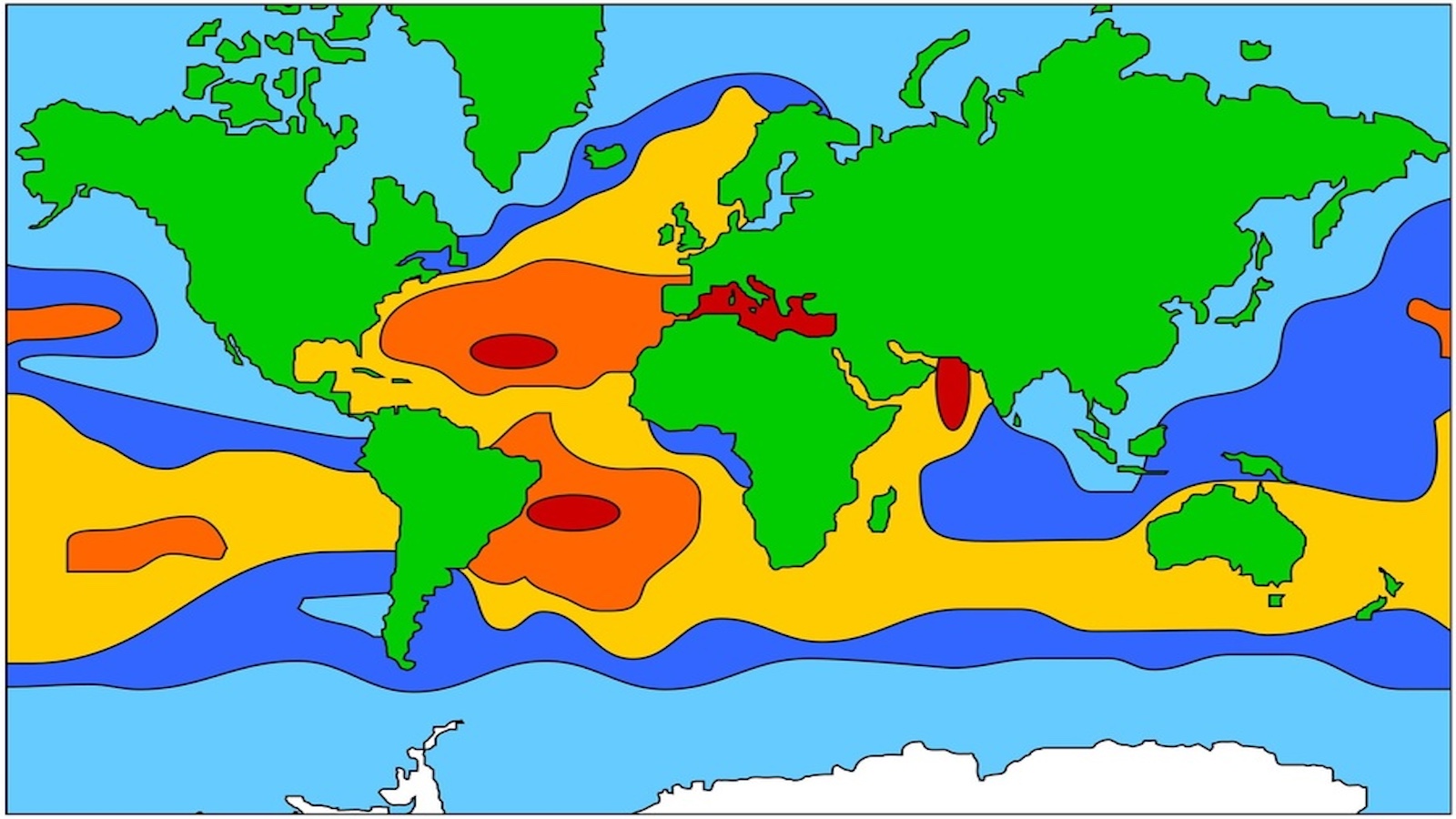

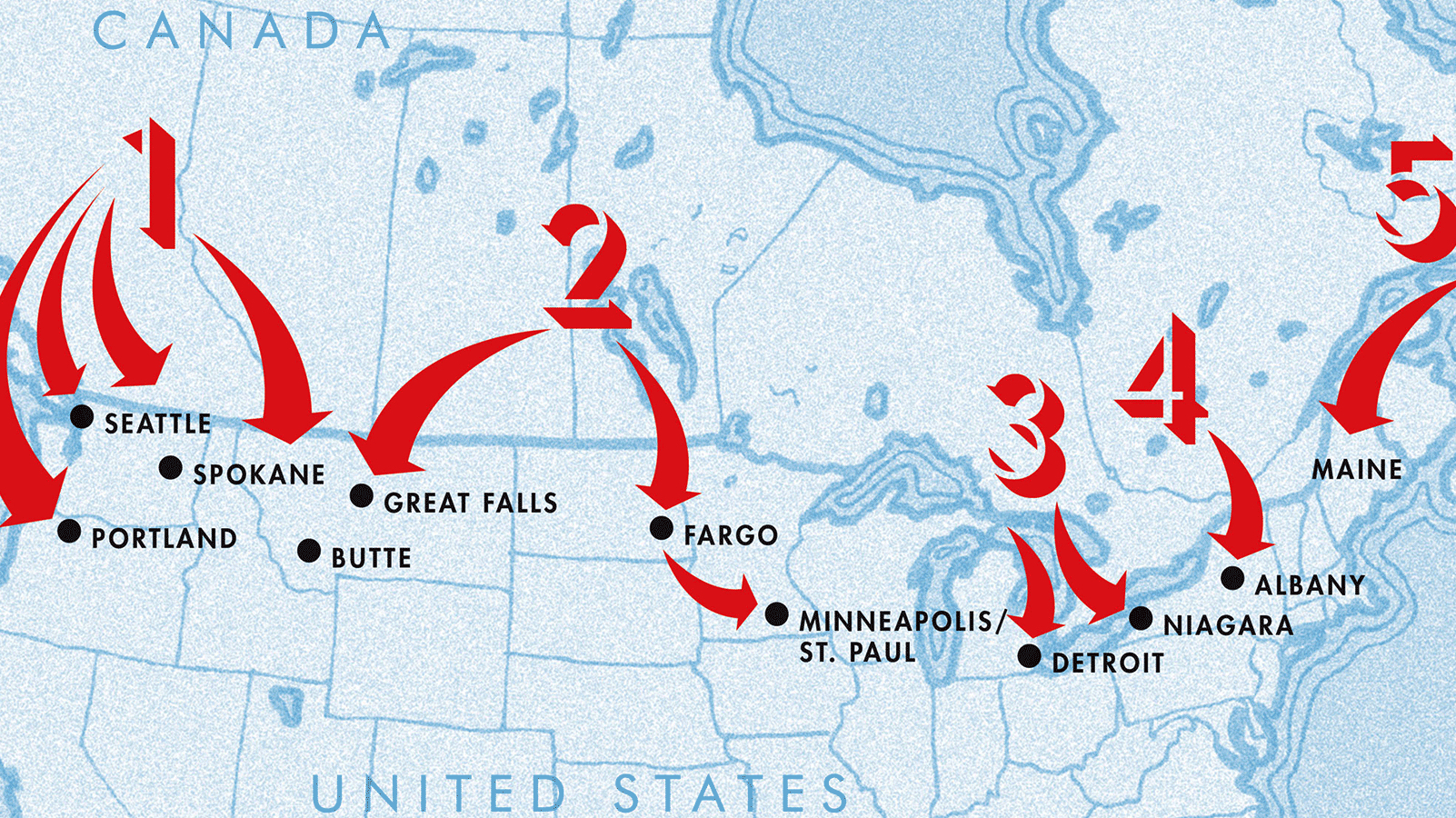

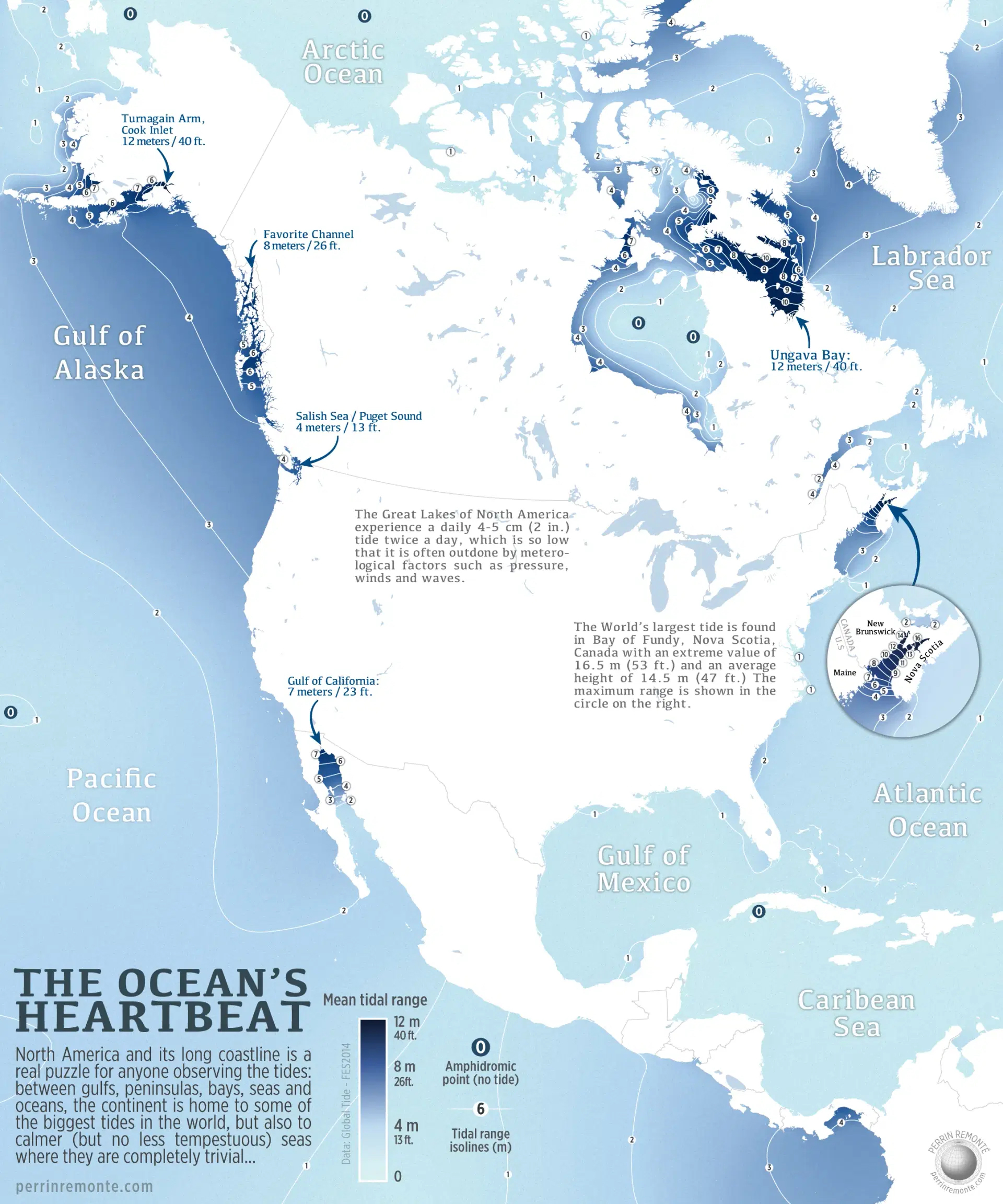

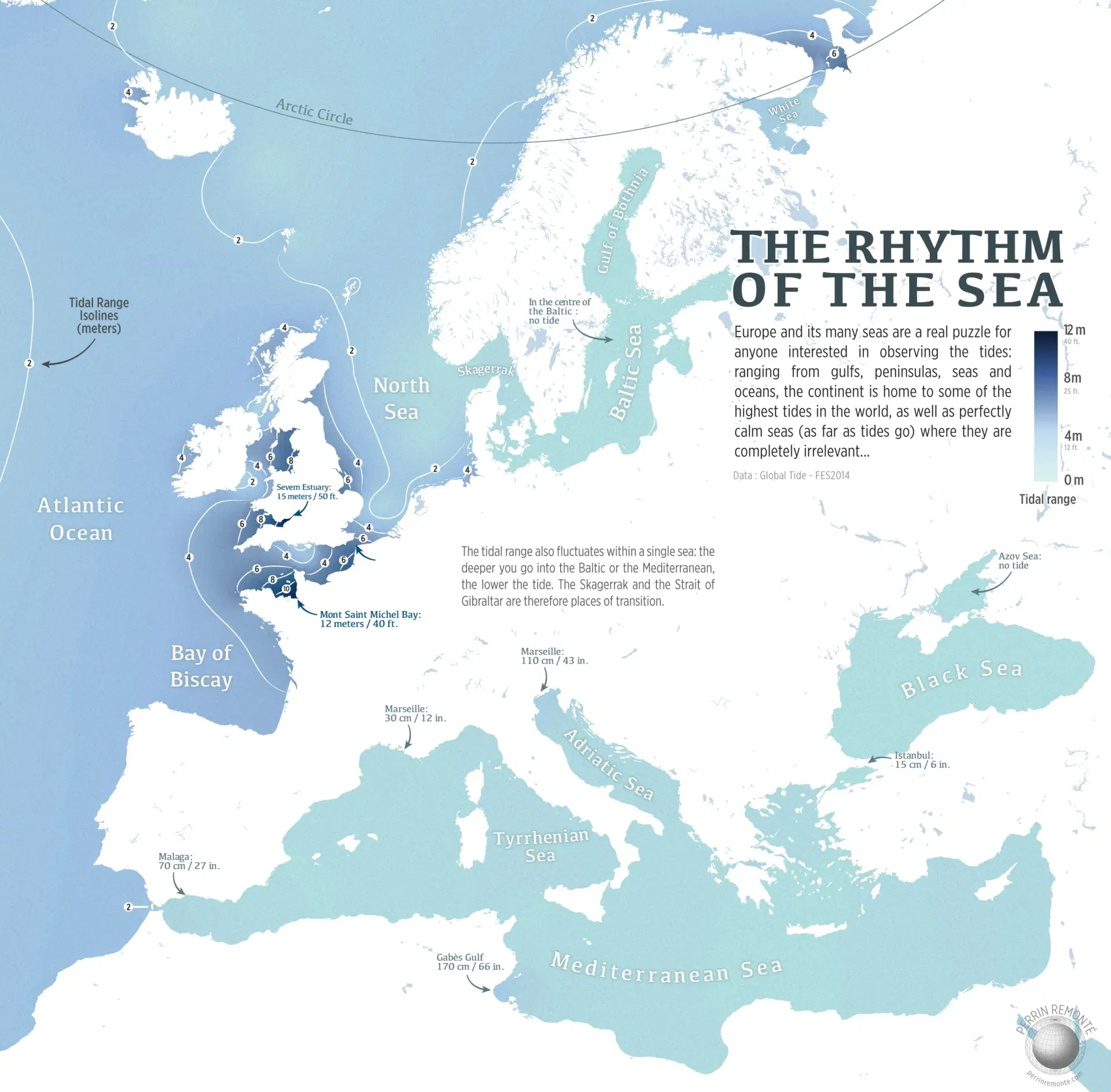

These maps show where you can find some of the world’s largest tidal ranges. Each blue patch, darker if the difference between high and low is greater, is a danger zone. Each one has its own set of horror stories; of drownings accidental and, occasionally, criminal.

The maps also illustrate why tides, which result from the gravitational force of the Moon (and, to a much lesser extent, the Sun), can be so treacherous. The global average for the tidal range is just one meter (3.3 feet), but local variance can be so extreme as to catch the unsuspecting visitor unawares.

Finally, the maps also hint at the mechanics of extreme tidal variation: The range tends to be higher where coastal zones are shaped as funnels (though shallowness and orientation also play a role).

The Bay of Fundy funnel

For the best example of the funnel principle, go straight to the place that has the world’s largest tidal range: the narrowing northern extension of the Gulf of Maine known as the Bay of Fundy — to be precise, the tip of the Minas Basin, the eastern of that bay’s two northern forks.

While tides at the southwestern coast of Nova Scotia, near the mouth of the Bay of Fundy, vary around 4 m (14 ft), the difference in Minas Basin, the narrow top of the funnel, is fourfold: 16.5 m (53 ft).

That amplification of tidal force has some spectacular consequences. During each half-day tidal cycle, around 100 billion tons of water flows in and out of the bay. That’s twice the volume that passes through all the world’s freshwater rivers during the same period.

The tide is so strong — in the Minas Basin, it’s equal to 8,000 locomotives, or 25 million horses — that it pushes water back up the rivers that flow into the bay, causing weird phenomena such as the Reversing Falls in the St John River, where water alternatively flows in both directions across a series or rapids close to the river’s mouth.

Can all that horsepower be converted into hydropower? According to a study by Acadia University, Minas Passage could generate 2,500 megawatts at peak flows, which is roughly equivalent to the output of two nuclear reactors, enough to meet the entire energy needs of Nova Scotia. While smaller pilot projects have been trialed, no undertaking of this magnitude is currently on the table.

Tidal range is about height — and distance

The power of the Bay of Fundy’s tides may not yet be powering Nova Scotia, but they are continuing to shape it. The tides have helped sculpt a series of cliffs and sea stacks that give the local coastline a dramatic character.

Tidal range is expressed in height, but if you’re a nonchalant foreshore walker, it may be helpful to realize that there’s a distance factor as well — important enough to be deadly, in some cases. In some places, the water in the Bay of Fundy retreats up to 5 km (3 miles) from where it was at high tide, and it comes rushing back at a speed of more than 10 m (33 ft) per minute.

According to a story published in 1896 called “A Tragedy of the Tides,” this phenomenon was used to murderous effect in colonial times. It tells of a young couple kidnapped in 1749 by local tribesmen, staked out in Tantramar Creek near Halifax, and left to drown as the tide came in. The speed at which the water rolled in prevented other colonists from saving the couple from drowning.

The Bay of Fundy is the most extreme example of a great tidal range but it’s by no means the only one along the coasts of North America. Other places where tides force water in and out of narrow conduits are Ungava Bay in northern Québec and the Turnagain Arm of Cook Inlet in Alaska (both 12 m, 40 ft); Favorite Channel, also in Alaska (8 m, 26 ft); the top of the Gulf of California in northern Mexico (7 m, 23 ft); and Puget Sound in the Pacific Northwest (4 m, 13 ft). Farther south, the Gulf of Panama also has a tidal range of up to 4 m, complicating maritime traffic in and out of the Panama Canal.

On the other hand, the Great Lakes are so (relatively) small and isolated that they experience a tidal range of no more than 4 to 5 cm (2 in.). That’s little enough to be nullified by the right amount of wind or atmospheric pressure.

Amphidromic points and tideless seas

The North American map also shows several amphidromic points: in the Arctic Ocean, in Hudson Bay, off Cuba, and near Hawaii. At these points, also called tidal nodes, there is virtually no change in sea level due to a combination of interference in these bodies of water, combined with the Coriolis effect.

Europe also has its share of tideless seas, notably the Sea of Azov — the eastern ear on the dog’s head that is the Black Sea — and the middle of the Baltic Sea.

There’s very little tidal action throughout the Mediterranean, though it generally increases toward the Strait of Gibraltar, its only unobstructed opening to the high seas. Tidal range is just 15 cm (6 in.) in Istanbul, 30 cm (12 in.) in Marseille, and 70 cm (27 in.) in Malaga, which is closest to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the range is 2 m (6.6 ft).

Located at the thin end of the Adriatic wedge, Venice (mislabelled as Marseille on this map) has a tidal range of up to 110 cm (43 in.), but that’s still not as much as the Gulf of Gabès in Tunisia (170 cm, 66 in.).

Most of the ebbing and flowing in Europe takes place off British shores, and in the English Channel, which separates the UK from France.

At its narrowest, the estuary of the Severn River, an aquatic shard piercing the southwestern flank of Britain, has a tidal range of 15 m (50 ft), the second largest in the world. Surfers make a sport of riding exceptionally high manifestations of the Severn Bore, the local version of the tidal countercurrent. In 2006, a railway engineer named Steve King surfed the Severn Bore inland for a total of 12 km (7.5 miles), a Guinness World Record.

The Morecambe Bay Cockling Disaster

A bit north on this map is Morecambe Bay, the indent just above the “8” on England’s west coast. As the UK’s largest expanse of intertidal mudflats, this is a favorite but dangerous place to pick cockles. In 2004, a group of 21 Chinese illegal immigrants, unfamiliar with the area’s fast-moving tides, were taken by surprise by the rising water and drowned. The Morecambe Bay Cockling Disaster is the deadliest tidal catastrophe in living memory.

On the other side of the English Channel, one of the world’s highest tidal ranges created one of the wonders of the medieval world: Mont Saint-Michel. This island fortress just off the French coast, located at the point where Brittany and Normandy meet, is accessible over land at low tide, but completely surrounded by water at high tide, making a prolonged siege impossible. Indeed, despite several attempts, the English never managed to capture the island during the Hundred Years’ War.

Attracting more than three million visitors annually, Mont-Saint-Michel is France’s most popular tourist destination outside of Paris. Those visitors are warned not to stray from the causeway that links the island to the mainland, as walking across the flatlands can get dangerous when the tide comes in.

While the tides around Mont-Saint-Michel surprised plenty of pilgrims in the Middle Ages, they pose less of a hazard these days. Land reclamation in Mont-Saint-Michel Bay and canalization of the local Couesnon River have contributed to a slow silting-up of the bay.

In recent years, a hydraulic dam and a new bridge replacing the old causeway have been built, helping to prevent Mont-Saint-Michel from becoming permanently attached to the mainland.

The tidal nature of the island has been saved, which is great. But pilgrim, beware of the rising water.

Strange Maps #1259

Maps by French cartographer Perrin Remonté, reproduced with kind permission. Check out his X feed and his website.

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook.