Here’s the view from humanity’s furthest spacecraft

Credit: NASA's Eyes, public domain

- Jimmy Carter was U.S. president and Elvis Presley was still alive in 1977, the year Voyager 1 was launched.

- Back in 1990, Voyager 1’s last picture showed Earth as nothing more than a ‘Pale Blue Dot’.

- Voyager 1 is now traversing interstellar space – here’s what our solar system looks like from there.

Voyager 1 lifting off from Cape Canaveral on September 5, 1977.Credit: NASA, public domain

What’s the farthest place that humanity has gone? For a practical answer to that question rather than a philosophical one, direct your gaze to Ophiuchus, an equatorial constellation also known as Serpentarius.

Speeding towards Rasalhague and the other stars that make up the ‘Serpent-bearer’ is Voyager 1, the furthest human-made object in the Universe. It’s currently 14.1 billion miles (22.8 billion km) from the Sun and speeding away at roughly 38,000 mph (61,000 km/h).

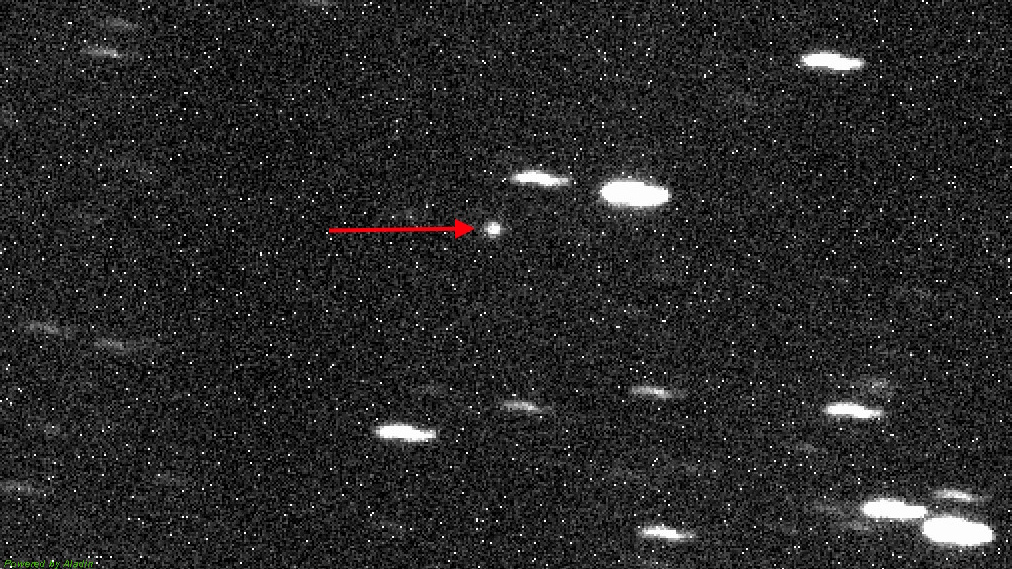

That’s too far to observe Voyager 1 twinkle in the night sky. But you can turn the tables and see what it sees, as it looks back at us. Via NASA’s Eyes website (and app), you can pay a virtual visit to where the spacecraft is now and explore its vantage as it hurtles towards the edge of the solar system.

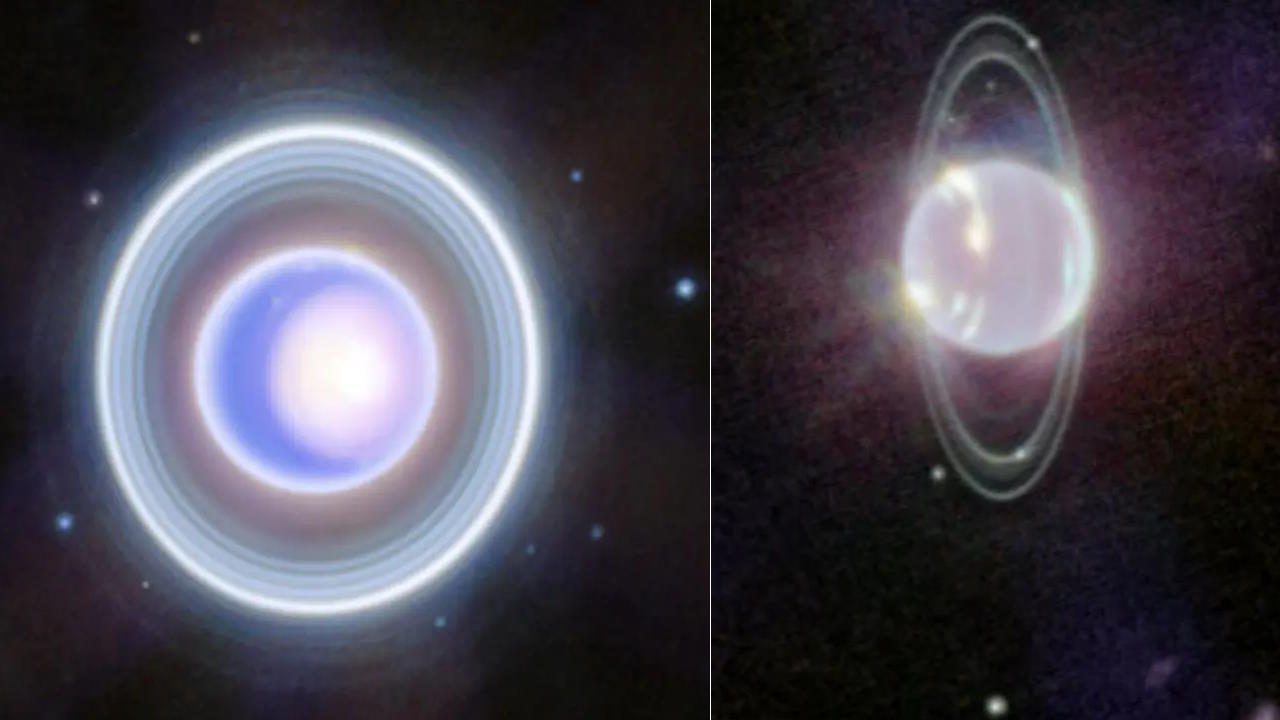

There’s Jupiter and Saturn, so seemingly close together; and Uranus, Pluto and Neptune, their orbits farther away. At the center of it all, the Sun. Nearby, the inner planets, including Earth: so close to it that they don’t even get a name-tag. Those planets and their trajectories are so familiar yet now so distant, it’s enough to make you homesick by proxy!

You can click and drag your way around Voyager 1, shifting your perspective to explore the region – spotting Sedna, Halley’s Comet and a few other less familiar members of our solar family.

Where it’s at: this is what the view of the solar system is from Voyager 1 as it speeds into interstellar space. Credit: NASA’s Eyes, public domain

Although it’s still sending data back to Earth, most of Voyager 1’s instruments have now been powered down, and the craft is expected to go entirely dead by 2030 at the latest; but its incredible journey isn’t over. In fact, it will most likely continue long after you, I and everything we know will have disappeared. Here’s how it all started.

The year is 1977. Jimmy Carter’s first year as president. Elvis Presley’s last year alive. Star Wars hits the big screen. On September 10, Hamida Djandoubi becomes the last person ever to be guillotined in France. Five days earlier, Voyager 1 takes off from Cape Canaveral.

Voyager 1 is a small craft, weighing barely 1,820 lb. (825.5 kg). Its most prominent feature is a 12-ft (3.7-m) wide dish antenna, for talking with Earth – when there’s no straight line of communication, a Digital Tape Recorder kicks in, able to hold up to 67 MB of data for later transmission. In all, Voyager 1 carries 11 different instruments to study the heavens.

Voyager 1 and its range of instruments, which have been progressively shut down as the craft’s power waned. Credit: NASA/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The idea for the Voyagers, 1 and 2, grew out of the Mariner program’s focus on the outer planets. The Voyagers got their own name as their field of study started to diverge towards the outer heliosphere and beyond.

The heliosphere is the ‘solar bubble’ created by the solar wind, i.e. the plasma emitted by the Sun. The region where solar wind slows down to below the speed of sound is called the termination shock. The heliopause is the outer limit of this bubble, where outward movement of solar plasma is nullified by interstellar plasma from the rest of the Milky Way. Beyond lies interstellar space.

The Voyagers were built to withstand the intense radiation in those far reaches of space – in part by applying a protective layer of kitchen-grade aluminum foil.

Humanity’s farthest probe into the Universe was launched on September 5, 1977, confusingly 16 days after Voyager 2. More than 43 years later, the craft is still sending data back to Earth – but not for very much longer. Here are a few snapshots for the family album:

- December 19, 1977: Voyager 1 overtakes Voyager 2. Voyager 1 is travelling at a speed of 3.6 AU per year, while Voyager 2 is only going at 3.3 AU. So, Voyager 1 is constantly increasing its lead over its slower brother.

- Early 1979: Voyager 1 flies by Jupiter and its moons, taking close-ups of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot and spotting volcanic activity on the moon Io – the first time ever this was observed outside Earth.

- Late 1980: flyby of Saturn and its moons, especially Titan. The flybys of the two gas giants gave ‘gravity assists’ that helped Voyager 1 continue its journey.

- February 14, 1990: Voyager takes a ‘Solar System Family Portrait’, its final picture and the first one of the solar system from the outside. It included an image of the Earth from 6 billion km (3.7 billion mi) away, as a ‘Pale Blue Dot‘.

- February 17, 1998: Voyager 1 reaches 69.4 AU from the Sun, overtaking Pioneer 10 and becoming the most distant spacecraft sent from Earth.

- 2004: Voyager 1 becomes the first craft to reach termination shock, at about 94 AU from the Sun. The Astronomic Unit (AU) is the average distance from Sun to Earth (about 93 million mi, 150 million km or 8 light minutes).

- August 25, 2012: after a few months of ‘cosmic purgatory’ and 10 days before the 35th anniversary of its launch, Voyager 1 became the first human-made vessel to cross the heliopause, at 121 AU, thus entering interstellar space.

- Soon after, Voyager 1 entered a region still under some influence of the Sun, which scientists dubbed the ‘magnetic highway’.

- November 28, 2017: all four of Voyager 1’s trajectory correction maneuver (TCM) thrusters are used for the first time since November 1980. This will allow Voyager 1 to continue to transmit data for longer.

- November 5, 2018: Voyager 2 crosses the heliopause, departing the heliosphere. Both Voyagers are now in interstellar space.

Artist’s impression of Voyager 1 passing the rings of Saturn in 1980.Credit: NASA/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

While both Voyagers have now left the heliosphere, that doesn’t mean they’re outside the solar system yet. The latter is defined as the vastly larger region of space, populated by all the bodies that orbit the Sun. The limit of the Solar system is the outer edge of the Oort cloud.

As available power declined, more and more of the Voyager 1’s instruments and systems have been turned off – prioritising the instruments that send back data on the heliosphere and interstellar space. It is expected that the last instruments will cease operation sometime between 2025 and 2030.

Travelling at just about 61,200 km/h (38,000 mph) relative to the Sun, the craft will need 17 and a half millennia to cover the distance of a single light year. Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun, is 4.2 light-years away. If Voyager 1 were going in that direction, it would need almost 74 millennia to get there. But it isn’t. So, what is next?

- In 2024, NASA plans to launch the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP), which will build on Voyager’s observations of the heliopause and interstellar space.

- In about 300 years, Voyager 1 will reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud.

- In about 30,000 years, it will exit the Oort Cloud – finally leaving the solar system altogether.

- In about 40,000 years, it will pass within 1.6 light-years of Gliese 445, a star in the constellation Camelopardalis.

- In about 300,000 years, it will pass within less than 1 light-year of the star TYC 3135-52-1.

- According to NASA, Voyagers 1 and 2 “are destined – perhaps eternally – to wander the Milky Way.”

Flying on board Voyagers 1 and 2 are identical ‘golden’ records, carrying the story of Earth far into deep space.Credit: NASA, public domain

Both Voyager 1 and 2 carry a Golden Record that contains pictures, scientific data, spoken greetings, a sampling of whale song and other Earth sounds, and a mixtape of musical favorites, from Mozart to Chuck Berry.

Perhaps in a distant future and place, some alien intelligence with a record player will have a listen to Blind Willie Johnson hum Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground, and think of us: “What a strange old planet that must have been.”

Image taken from the Voyager 1 page at NASA’s Eyes.

Strange Maps #1065

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.