Watercolours of the War Between East and West

9/11 was the beginning of a new kind of war — asymmetric, global, high-tech. But it’s also the continuation of a conflict as old as recorded history: the struggle between East and West.

Ted Danforth had a printing shop in Manhattan a few blocks from the World Trade Center when those two planes hit. In his victory video, Osama Bin Laden later hailed the attacks as revenge for “80 years of humiliation and disgrace” for “our Islamic nation.”

Why 80 years exactly? That puzzling reference piqued the interest of Danforth, and the printmaker-scholar’s research blossomed into a series of lectures that now culminate in The Eastern Question.

This highly original book reveals how ancient threads of history, geography, and politics interlace to form the fabric of today’s troubles — a conflict so old, in fact, that it predates both America and Islam by many centuries.

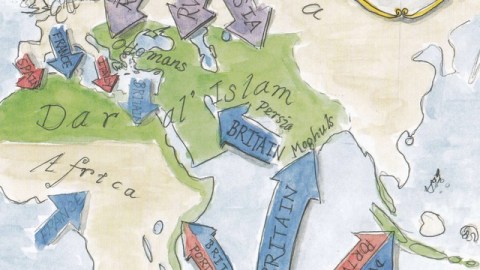

Illuminating the book are 108 watercolour maps and drawings, all by the author, to illustrate and clarify The Eastern Question‘s many excellent points.

As this blog is about maps rather than books, I’ll just zoom in on a few examples of the curious cartography in The Eastern Question. For a more comprehensive overview of the book itself, find a proper review, or better still: Get the book — both entertaining and educational, brimming with broad vision (“Imagine the fallen Roman Empire as a giant broken egg”) and big on anecdotes (the Turkish name “Istanbul” derives from Greek signposts reading eis tèn polin, “towards the City”); it’s one of the best geopolitical capers of the past years.

Europe is a fluid concept. It used to stop where the Ottoman Empire started. The back and forth between both is transposed on a battlefield of another type — American football. Constantinople’s fall to the Turks in 1453 was the start of Ottoman ascendancy. Its main opponent was Europe’s frontline state, the Habsburg Empire. The Ottoman high-water mark was the failed siege of Vienna in 1683. By the end of the First World War, when the Allies briefly occupied Istanbul, history seemed to have come full circle.

Few people think of Attila as one of the fathers of Europe, but Völkerwanderung he initiated chased a lot of tribes to locations that still bear their imprint: the Angles to England and the Franks to France, for example. Danforth suggests an interesting visual analogy: “Imagine (Attila) as a pool player striking the racked-up balls at the beginning of the game and, with one powerful strike of the cue, scattering the tribes of Europe.”

For much of its millennial struggle with Islam, Europe was the weaker of both sides. Hence the Arab incursion into Spain, all the way up to Poitiers, and the Turkish conquest of Byzantium and the Balkans. That Europe didn’t fall, is due to its peninsularity, a natural defence. Picture the continent as a classic fortress, containing three concentric walls. The Ottomans breached the Eastern Orthodox counterscarp, allowing the Grand Turk to pitch his tent before Vienna. But the bastion held, and Catholic Habsburg saw off the threat. The innermost circle of defence, the cavalier of Protestant northern Europe, was never directly in danger.

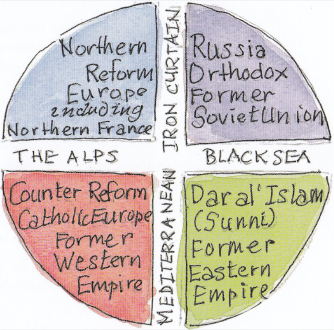

T-O maps were popular in the Middle Ages. They showed the circle of the known world divided into Europe, Africa and Asia by the T-shaped waters of the Mediterranean and Red Seas, with Jerusalem at its symbolic centre. This updated version divides the orbis terrarum in quadrants to make geopolitical sense: “Starting in the lower quadrant, we have the Former Eastern Empire — now Dar al’Islam, the most powerful state of which was the Ottoman Empire. It lies to the east of Europe and is divided from it by the Mediterranean Sea and the Balkans. In the lower-left quadrant, we have Counter-Reform Catholic southern Europe. In the upper-left quadrant, we have the rising power of northern Europe — the lands of the Reform, the Enlightenment, and the modern corporation. To the east is Orthodox Russia, later the Soviet Union. Between them, during the Cold War, was the Iron Curtain. And coming full circle, to the south of Russia, across the Black Sea, was the Ottoman Empire.”

Crucially, “with the decline of the southern quadrants in the 17th century, the struggle between East and West moved north.”

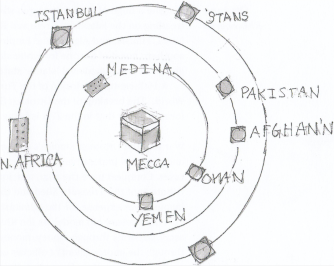

Danforth manages an entire book about East and West without once referring to that tired Rudyard Kipling quote (“never the twain shall meet”), for which he is to be commended. Instead, he observes the conceptual difference between churches and mosques. Christian places of worship face east (hence our word “orientation”), while the qibla (“direction”) of worship in a mosque is always towards Mecca. As the author notes, almost esoterically: “The difference between mosque and church is the difference between Time and Space. The Western church reflects Time in the form of Space, while the mosque reflects Space in the form of a circle whose center is the Ka’aba in Mecca.”

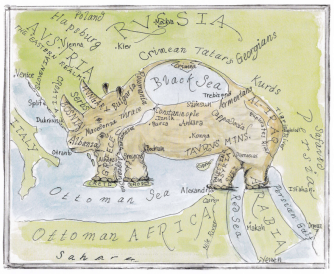

Long-time readers of this blog may remember the Southern Ontario Elephant (#340). They will be delighted to make the acquaintance of his distant cousin, the Ottoman Rhino. “Imagine a huge African rhinoceros sticking its horns into the Balkans, its forefeet treading on the islands of Crete and Rhodes, its back feet on Egypt and Arabia.”

This is what Osama was talking about: the “humiliation and disgrace” suffered by the Islamic nation during the long ascendancy of the West, which got so used to conquest that it stopped considering its consequences.

After the Enlightenment, Europe no longer perceived geopolitics as the struggle between religious world views. That didn’t stop the East from still doing so.

The Middle East is ground zero for the most inextricable, seemingly interminable conflicts in the war between “East” and “West.” It becomes hard to distinguish one brand of fanaticism from the other. As the French saying goes, les extrèmes se touchent — nicely illustrated by these two maps, each representing an irredentist daydream of Spanish-castle proportions: “The dream of a ‘Greater Syria’ was shattered in 1920, the ‘Year of the Catastrophe’ (Am al-Nakba) when the promised independent Arab state of the British was turned over to the French under the terms of Sykes-Picot. Today ISIS, a classic Islamic rebel state, is fighting for an ancient concept of the region. Both ISIS and Syrian dreamers see the present-day borders of the country as illegitimate imperial divisions imposed on the region as part of the settlement of the Eastern Question.”

“On the other hand, some in Israel, and even in the U.S., dream of a ‘Greater Israel,’ whose borders are essentially coterminous with those of a ‘Greater Syria.’ This is eretz yisrael, the Promised Land of Genesis (15:18), stretching from ‘the river of Egypt’ to the great river, the river Euphrates.”

Danforth’s fascinating crash course in geopolitics is worth reading again, not just for the maps, but also for the deep historical context it provides to so much of the world’s current conflicted state. Unfortunately, it is a book without a neat conclusion (or as Europeans call it, an “American ending”). The realisation that there are impersonal forces at work in the world that are both more consequential and less visible than human stupidity is liberating and depressing at the same time.

Images reproduced with kind permission. More on the book on its companion website.

Strange Maps #746

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.