Braille-Inspired Design for The Blind

Design, at its best, improves our quality of life, an enhancer of the senses and an enabler of our best possible selves. Nowhere is its power more palpable than in instances where a deficit of the senses impairs that quality of life. Last week, we looked at how designers are revolutionizing corrective eyewear for those with imperfect vision. Today, we’re looking at an even more onerous design challenge: Helping those with no vision at all.

No conversation about design for the blind can begin without recognizing that the Braille system is indisputably one of design’s greatest claims to good. Consequently, many of the design-driven approaches to blindness incorporate Braille to make everything from utilitarian necessities to playful diversions accessible for the blind. To mark the 200th birthday of Louis Braille last year, The Netherlands’ national post service launched a series of postage stamps by graphic designer Rene Put, featuring typographic abstractions alongside embossed Braille text, making them legible for both the sighted and the blind. The project was a winner at the Dutch National Awards in November.

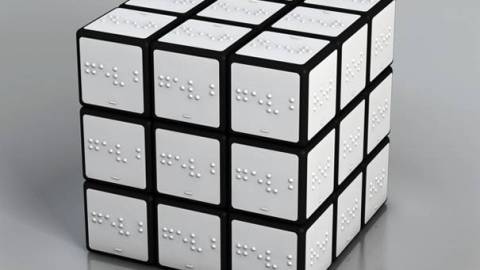

From German designer Konstantin Datz comes a Braille Rubik’s Cube, a lovely celebration of making a cultural classic as inclusive as possible.

Along the same lines of making playtime an equal-opportunity endeavor, Tactile Mind, an erotic book for the blind, offers 17 raised images of nudes for adults. Creator Lisa Murphy was inspired by the realization that the blind have been generally left out of a culture saturated by sexual imagery — a point further illustrated by the fact that between 1970 and 1985, Playboy, the quintessential epitome of lascivious image with a side of vastly ignored text, published a Braille version in partnership with The National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS), but the magazine only included the text of the non-Braille version, omitting the images altogether in a bout of tragicomic irony.

And in 2008, designers Son Seunghee, Lee Sukyung and Kim Hyunsoo won a Red Dot award for their Braille Polaroid Camera, which allows blind people to to capture and print Braille images of the world around them using a built-in Braille printer.

While these projects do offer an interesting direction of design thinking as a tool for enriching the day-to-day quality of being and pure life enjoyment of the blind, the central caveat is that many of them remain at the concept stage and never reach a mass market. Meanwhile, ambitious nonprofit efforts are taking tangible steps towards liberalizing content for the blind — just last week, the Internet Archive launched a new service bringing more than 1 million books to the visually impaired. And if design is to truly become a change agent, it has learn to be as grounded in policymaking and advocacy as it is in conceptual aestheticism.

Maria Popova is the editor of Brain Pickings, a curated inventory of miscellaneous interestingness. She writes for Wired UK, GOOD Magazine and Huffington Post, and spends a shameful amount of time on Twitter.