Can New Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations Help Reduce the Harm of Cancer Phobia?

For decades, cancer has been the disease people fear most. Understandably. Study of the psychology of risk perception has established that we worry more about risks over which we have no control, and “You have cancer” has always seemed like an inescapable, can’t-do-anything-about-it death sentence. We are more afraid of threats that involve greater pain and suffering — what the academics call “dread” — and many of the more than 150 types of cancer certainly involve great suffering. We are more afraid of risks that seem like they are imposed on us, caused by something done to us by others, and decades of advocacy campaigns have created a widespread belief that cancer is caused by external environmental triggers far more than is the case.

Against all this fear of cancer we are only beginning to realize that the fear itself may cause serious harm, in some cases more than the disease itself. The American Cancer Society’s new recommendations on breast cancer screening (spelled out in far more detail here) imply precisely that. They recommend that:

+ women not otherwise at high risk not begin screening until age 45, the average age at which breast cancer really begins to spike (previously they recommended starting at age 40),

+ that women screen less frequently after age 55 (once every other year instead of annually, because breast cancers grow more slowly after menopause),

+ and that breast exams no longer need be part of regular visits to the doctor.

It recommends all these changes, it says, because the evidence shows that earlier screening, more frequent post-menopausal screening, and regular exams by doctors don’t save any lives.

It’s going to be really hard for women who have always believed that earlier and more frequent screening gives them something they can do to reduce their risk, to let go of that reassuring sense of control, and screen less.

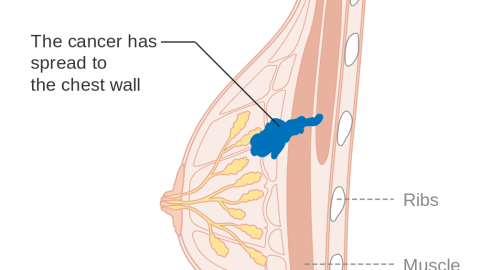

What it also says, bravely, is that those earlier and more frequent screenings appear to do more harm than good. They turn up all sorts of false positive or equivocal results that scare women into biopsies, follow-up tests, mastectomies, and cause chronic worry and stress, all of which do real physical harm, even though the evidence finds that, across the whole population, screenings earlier and more frequently than these recommendations do not save lives. Many early screening tests turn up Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS), which in many cases never grows or spreads, and frequently just disappears on its own. Yet many DCIS cases get treated like full-blown life-threatening disease because, let’s face it, when a woman hears she has a lump or a shadow in her breast, and its description has the word carcinoma in it, what’s she going to do? Wait and see what happens?

These new recommendations will be surely controversial. Experts will debate the epidemiological evidence of whether early and more frequent screening save lives. But the real controversy won’t be among those experts and it won’t be about the facts. It will be among the women who face these difficult scary choices, and who will view these objective recommendations and the factual evidence through the subjective emotional lens of how the threat of breast cancer feels.

It’s one thing for experts to warn what our fears might cause, as Dr. Nancy Keating essentially did in the Journal of the American Medical Association:

For many years, we convinced everybody, including doctors, that mammograms are the best tests and everyone has to have one. But now we’re acknowledging that the benefits are modest and the harms are real.

It’s another for 42-year-old Eunice, who has always been told that screening should start at 40 that now, “Don’t worry, Eunice. It’s okay to wait.” It’s another thing to tell 59-year-old Amy, who has always believed that she can reduce her chance of breast cancer with yearly exams that, “Don’t worry, Amy. Every other year is enough.” It’s another thing to tell middle-aged Mei Lee that having her doctor — a trusted medical expert — do a reassuring breast exam whenever she visits, is reassurance that has no value.

[T]he real controversy won’t be among those experts and it won’t be about the facts. It will be among the women who face these difficult scary choices…

That may be what the facts and the experts say about risks for the average women population-wide, but the deep fear of cancer is going to make it really hard for individual women to consider such expert advice objectively and change how they feel.It’s going to be really hard for women who have always believed that earlier and more frequent screening gives them something they can do to reduce their risk, to let go of that reassuring sense of control, and screen less. Even though that may actually be what’s best for their health.

This isn’t just about breast cancer, or gender. Men make these choices with prostate cancer, screening earlier and more frequently than evidence-based guidelines suggest, doing themselves harm with procedures or surgeries their conditions don’t require. This is also not about what’s right or wrong. Who is to say that a woman who removes a DCIS lump, or a 40-year-old man who risks impotence to remove a slow growing prostate tumor that would probably never harm him, are wrong? Not me. Indeed the fear of cancer is so real it can do lots of serious harm all by itself, from the myriad profound effects of chronic stress, which, among other things, weakens the immune system and makes it more likely you’ll get sick — including develop cancer. Getting rid of the stress from persistent fear is good for health too.

This is about how these new breast cancer screening recommendations are an important step as we enter a new era in our relationship to our most feared disease. Not only are we learning that we are not powerless against cancer — more and more forms of the disease are being successfully treated — but we are just beginning to recognize that fear of cancer can be a risk too, and sometimes that fear can do more harm than the disease itself. For bravely sending that message to women, despite the controversy these new breast cancer screening recommendations will spark, the American Cancer Society is to be applauded.

—

(Image: Lilli Day, Getty Images)