Dense stellar clusters may foster black hole megamergers

Black holes in these environments could combine repeatedly to form objects bigger than anything a single star could produce.

Jennifer Chu | MIT News Office

When LIGO’s twin detectors first picked up faint wobbles in their respective, identical mirrors, the signal didn’t just provide first direct detection of gravitational waves — it also confirmed the existence of stellar binary black holes, which gave rise to the signal in the first place.

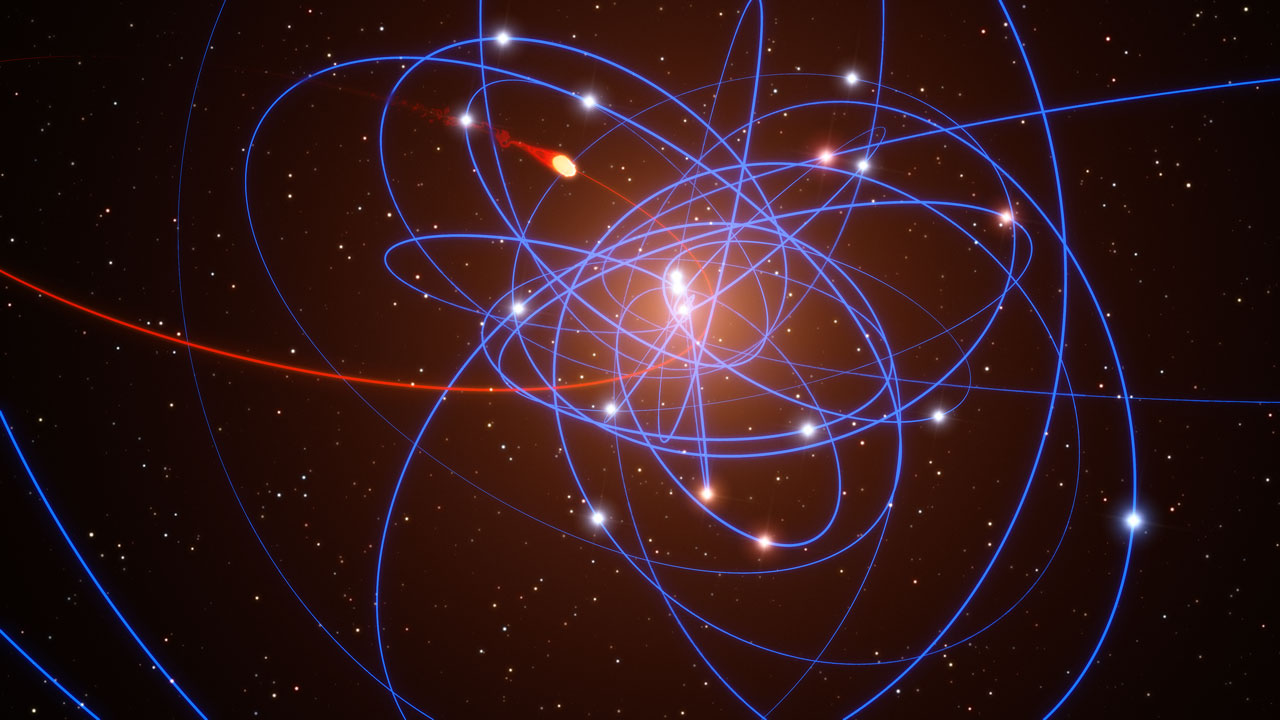

Stellar binary black holes are formed when two black holes, created out of the remnants of massive stars, begin to orbit each other. Eventually, the black holes merge in a spectacular collision that, according to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, should release a huge amount of energy in the form of gravitational waves.

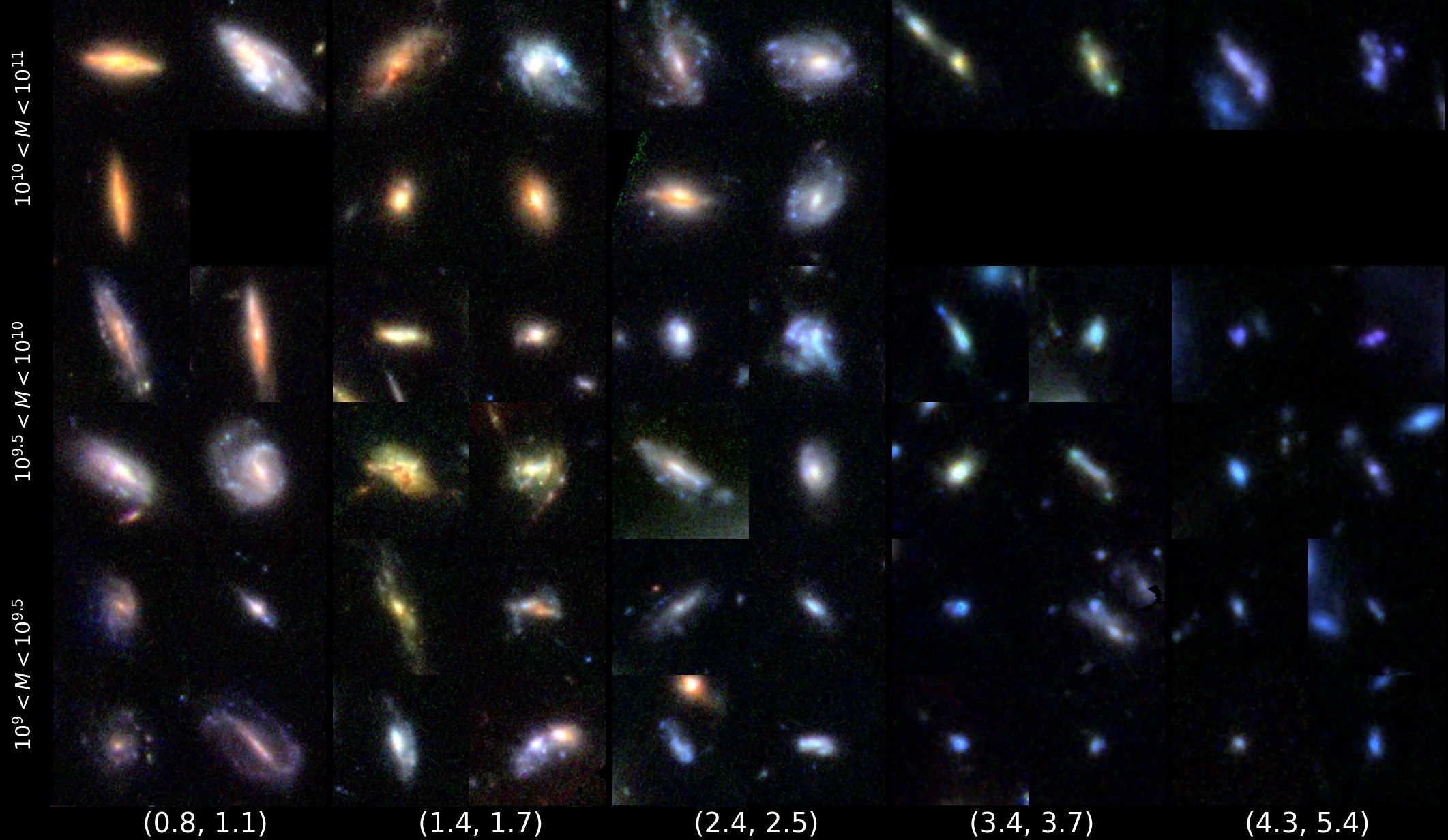

Now, an international team led by MIT astrophysicist Carl Rodriguez suggests that black holes may partner up and merge multiple times, producing black holes more massive than those that form from single stars. These “second-generation mergers” should come from globular clusters — small regions of space, usually at the edges of a galaxy, that are packed with hundreds of thousands to millions of stars.

“We think these clusters formed with hundreds to thousands of black holes that rapidly sank down in the center,” says Carl Rodriguez, a Pappalardo fellow in MIT’s Department of Physics and the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “These kinds of clusters are essentially factories for black hole binaries, where you’ve got so many black holes hanging out in a small region of space that two black holes could merge and produce a more massive black hole. Then that new black hole can find another companion and merge again.”

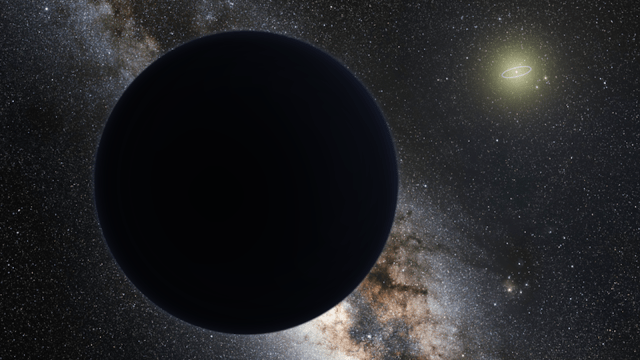

If LIGO detects a binary with a black hole component whose mass is greater than around 50 solar masses, then according to the group’s results, there’s a good chance that object arose not from individual stars, but from a dense stellar cluster.

“If we wait long enough, then eventually LIGO will see something that could only have come from these star clusters, because it would be bigger than anything you could get from a single star,” Rodriguez says.

He and his colleagues report their results in a paper appearing in Physical Review Letters.