What Killed off the Neanderthals? You Might Not Like the Answer

PIERRE ANDRIEU | Credit: AFP/Getty Images

Beginning about 400,000 years ago, Neanderthals began moving across Europe and Western Asia. They roamed widely for hundreds of thousands of years. Then something happened about 45,000 years ago. That’s when a new, invasive species turned up on the scene, homo sapiens—our direct ancestors. This group began migrating across Africa and into Europe. Waves of them came and spread out. The next bit has been a mystery to modern science. 5,000 years later, the Neanderthals disappeared. No one knows why. But a new discovery has us one step closer to a definitive answer.

One thing to note, the process of extinction is so complex, it is hard to understand why certain species vanish today, never mind tens of thousands of years ago. That said, there are many theories. Some have posited that our ancestors killed off the Neanderthals in disputes over precious resources. Others believe the two intermarried. Indeed, a smidgen of Neanderthal DNA has been found in the human genome, and resides within anyone whose ancestry lies outside of Africa, a place where Neanderthals never stepped foot. Another theory is that an alliance between wolves and humans gave them a competitive edge over their hominid cousins.

Until now, one of the leading theories was that climate change and competition did them in. Neanderthals were specialized to hunt large, Ice Age animals. When the last Ice Age rescinded, these animals died off, and the Neanderthals with them. Homo sapiens are also thought to have developed trade routes over long distances, giving them access to food and other resources during times of scarcity. Now a new collaborative study, published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, has added another theory. Homo sapiens would have carried tropical diseases with them out of Africa, infecting Neanderthals and speeding up their annihilation.

A handsome Neanderthal.

Researchers at Cambridge and Oxford Brookes Universities, both in England, posed this theory. They did so after finding genetic evidence that infectious diseases were tens of thousands of years older than first surmised. Since both species were hominin, it would have been easy for pathogens to jump from one to the other. Investigators examined the DNA of pathogens found in ancient human fossils, and the DNA of the fossils themselves, to come to these conclusions.

Strong evidence suggests that homo sapiens mated with Neanderthals. By doing so, they would have transmitted genes associated with disease. Since there is evidence that viruses moved from other hominins to homo sapiens in Africa, it makes sense that these could in turn be passed on to Neanderthals, who had no immunity to them.

Dr. Charlotte Houldcroft was one of the researchers involved with this study. She hails from Cambridge’s Division of Biological Anthropology. Houldcroft called homo sapiens migrating out of Africa reservoirs of tropical disease. She said that many pathogens, such as tuberculosis, tapeworms, stomach ulcers, even the two different kinds of herpes, may have been transmitted from early humans to Neanderthals. These are chronic diseases which would have weakened Neanderthal populations substantially.

We may be reminded by the aftermath of Columbus and how small pox, measles, and other illnesses ravaged the inhabitants of the so-called New World. Houldcroft says this comparison is not accurate. “It’s more likely that small bands of Neanderthals each had their own infection disasters, weakening the group and tipping the balance against survival,” she said.

Early humans.

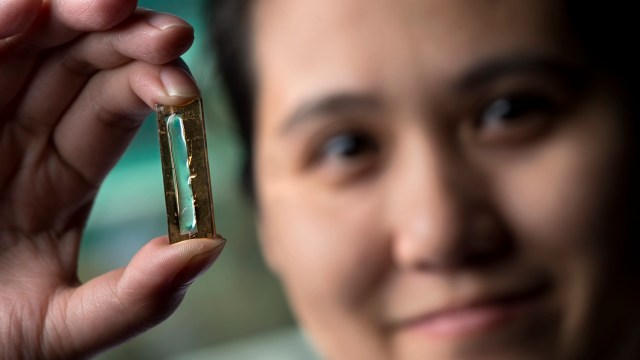

This discovery was made possible through new DNA extraction methods from fossils to search for traces of illness, as well as new techniques in deciphering our genetic code. Dr. Simon Underdown was another researcher whose work helped formulate this theory. He studies human evolution at Oxford Brookes University. Dr. Underdown wrote that the genetic data from many of these pathogens suggests that they may have been, “co-evolving with humans and our ancestors for tens of thousands to millions of years.”

Previous theories state that epidemics of infectious diseases broke out at the beginning of the agricultural revolution, around 8,000 years ago. At that time, previously nomadic populations began settling down with their livestock. Many pathogens mutate and jump to humans from animals. These are known as “zoonoses.” This dramatic change in lifestyle created the perfect environment for epidemics to occur. The latest research suggests however that the spreading of infectious diseases over a widespread area predates the dawn of agriculture entirely.

One example, it was thought that tuberculosis jumped from livestock to homo sapiens. After in-depth research, we now know that herd animals became infected through consistent contact with humans. Though there is no direct evidence that infectious diseases were transmitted from humans to Neanderthals, strong evidence of interbreeding leads researchers to believe that it must have occurred.

While early humans, used to African diseases, would have benefited from interbreeding with Neanderthals, as they would procure immunity to European-borne illnesses, Neanderthals would suffer from the transmission of African diseases to them. Though this doesn’t completely put the mystery to rest, according to Houldcroft, “It is probable that a combination of factors caused the demise of Neanderthals, and the evidence is building that spread of disease was an important one.”

To learn more about the extinction of the Neanderthals click here: