How exercise helps your gut bacteria

National Institutes of Health

- Two studies from the University of Illinois show that gut bacteria can be changed by exercise alone.

- Our understanding of how gut bacteria impacts our overall health is an emerging field, and this research sheds light on the many different ways exercise affects your body.

- Exercising to improve your gut bacteria will prevent diseases and encourage brain health.

Exercise gets a lot of attention for a lot of little things — like the mere fact that it can make you feel happier, that its good for your muscles and bones, increases your energy levels, benefits your mental health and memory, and lowers the risk of chronic disease — but did you know that exercise also helps your gut bacteria?

What is gut bacteria?

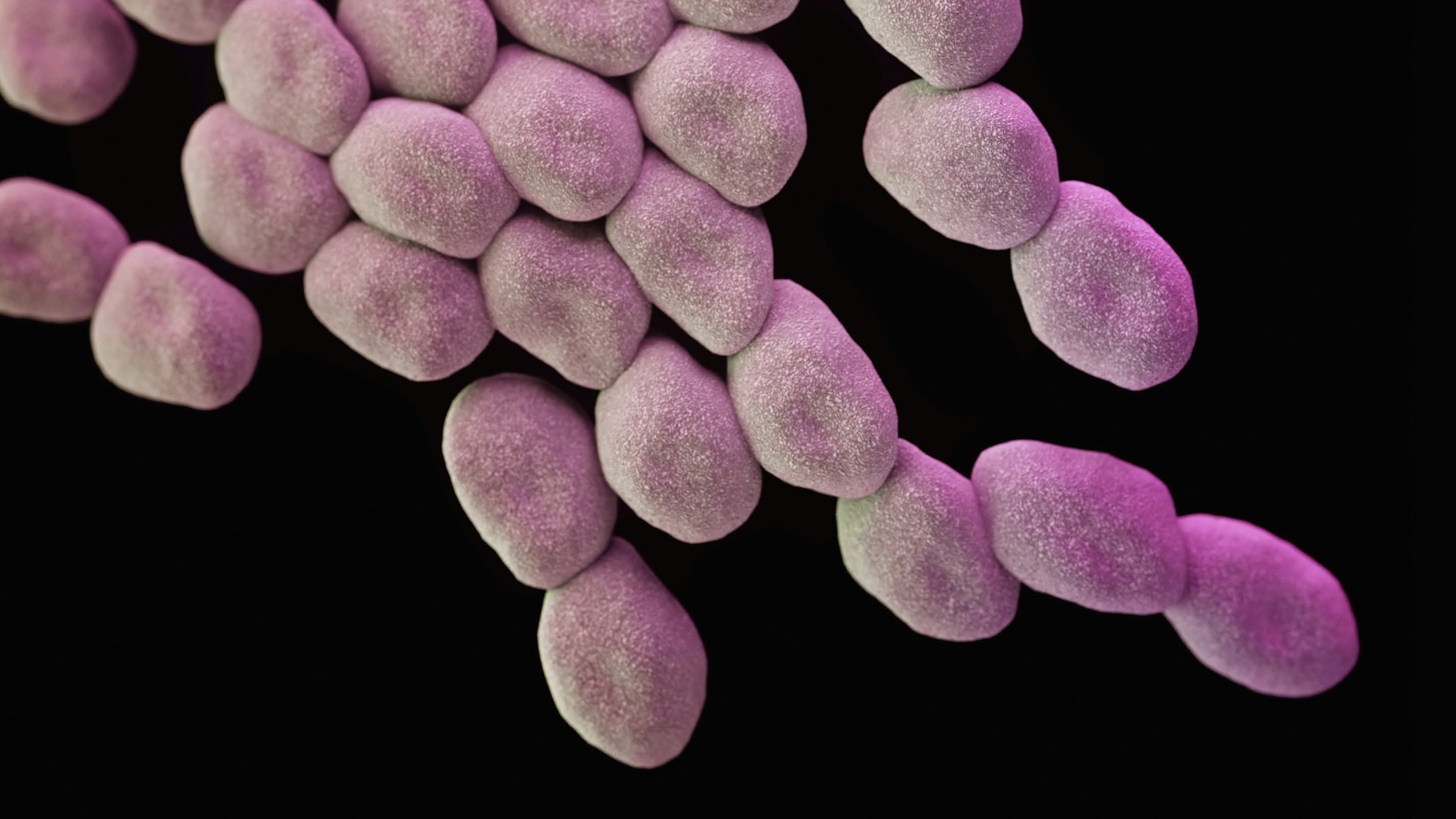

The 100 trillion bacteria in your gut come in 300-500 different varieties. There are nearly two million genes contained within that bacteria. All that bacteria helps regulate your gut. It also has an impact on your metabolism, mood, and the immune system, as well as on illnesses — in particular, type II diabetes, heart disease, inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, colon cancer, anxiety, depression, autism, and arthritis. The sheer scale of bacteria in the gut is a testament to the gut’s complexity. As recently as 2013, a paper in Gastroenterology & Hepatology called the recent awareness of the gut’s importance “a new era in medical science.”

You don’t have to train as a sprinter to give your gut bacteria a boost, but it won’t hurt. Image source: Roman Boed via Flickr

How exercise helps

Something new emerges from the world of gut bacteria seemingly every other day. That’s why it’s worth taking a look at two studies from the University of Illinois that were published near the end of 2017. One study focused on mice; the other study focused on humans. With the mice, the fecal matter from mice who had exercised was transplanted into mice who had and hadn’t exercised. The mice who had exercised had a healthier reaction to the fecal matter transplant than the mice who hadn’t, demonstrating the beneficial effects of exercise on the gut.

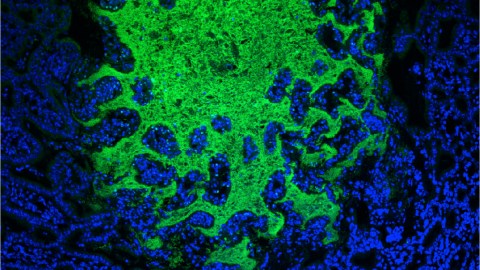

In the human study, 32 obese and lean individuals were tested. They did supervised cardiovascular exercises for 30-60 minutes three times a week for six weeks. Short-chain fatty acids — in particular, butyrate, which promotes healthy intestinal cells, reduces inflammation, and generates energy — increased in the lean participants as a result. Short-chain fatty acids in general are formed when gut bacteria ferment fiber in the colon. In addition to butyrate’s specific role, these fatty acids also improve insulin sensitivity and protect the brain from inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases.

Butyrate’s role in your gut manifests itself in a variety of ways: if you have Crohn’s disease, an increase in butyrate production can strengthen your intestines. It also plays a role in guarding the body against diet-induced obesity.

The study also found that lean individuals produced more butyrate than in obese individuals. Why this happened is still unknown and represents the next question for researchers to explore.