In space, there really might be no place like home

Few topics in science command as much attention as the discovery of extrasolar planets — those as-yet-unseen worlds, light years beyond our own Sun. In the quest to learn whether we are alone in the cosmos, astronomers are teasing out subtle wobbles and periodic dimmings of distant stars: telltale signs that a planet, much too faint to see directly in telescopes, is nevertheless present.

Alien giants, more massive than Jupiter, were the first to be discovered, whizzing around their nearby stars in frenetic orbits of a few days. Their great mass created the maximum possible stellar perturbations. But since we’ve passed the 20th anniversary of the discovery of the first exoplanet, the focus has shifted from behemoths to worlds more like Earth.

‘Earth-like’ evokes different meanings for different people. Astronomers tend to focus on three characteristics that they can confidently measure: radius, mass and orbit. Earth-like radii are inferred from the maximum dimming of the star as the planet eclipses a tiny fraction of its light, while mass can be calculated from the extent of stellar wobbling. Orbital parameters must place the planet within the ‘habitable zone’ — the donut-shaped volume of space where liquid water might persist at or near the planet’s surface. Growing numbers of discoveries — Kepler 186f, Kepler 438b, Kepler 452b (all identified by data from the Kepler space telescope) – approximate these astronomical constraints. Almost monthly headlines herald the most ‘Earth-like’ planet yet.

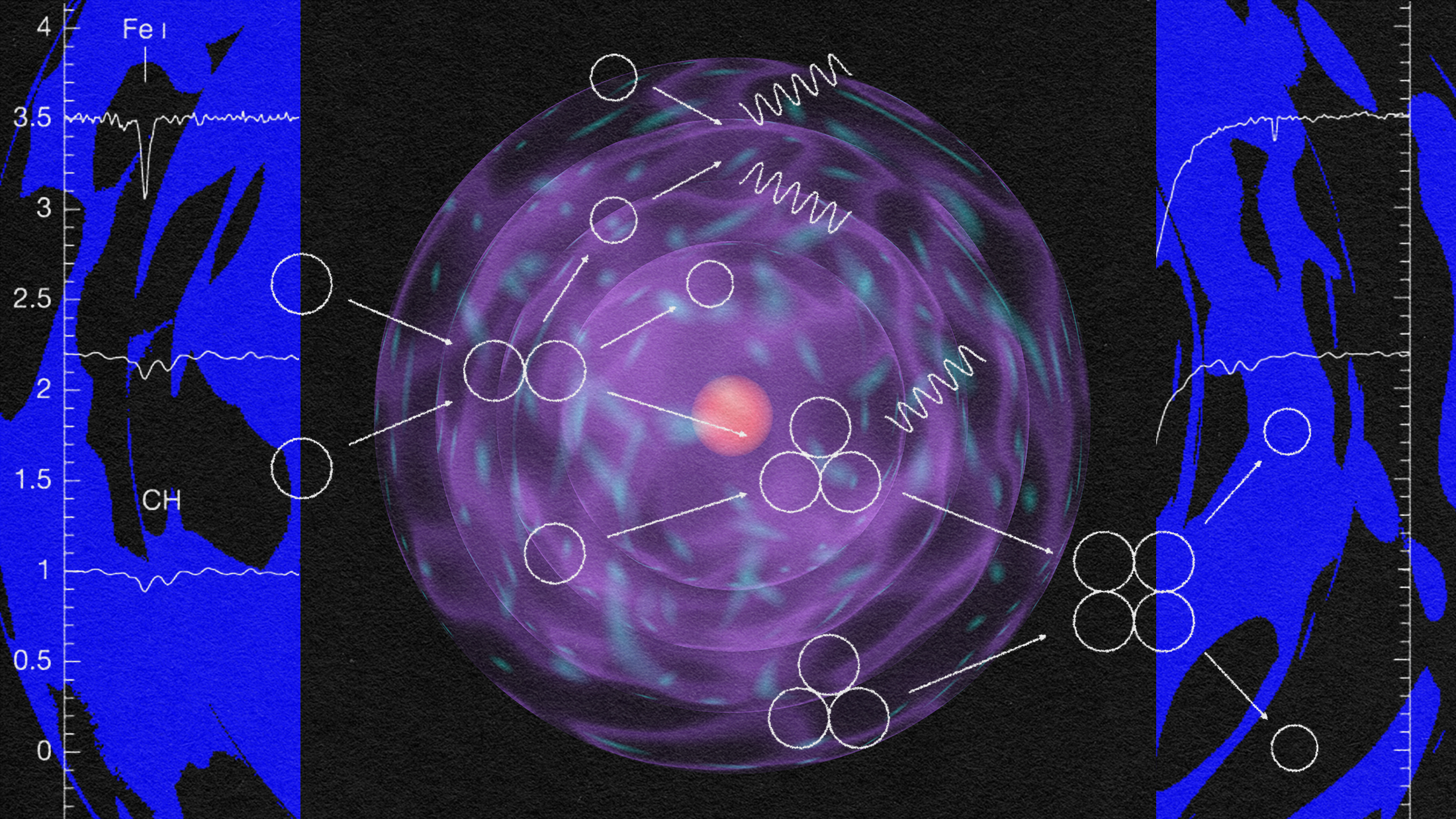

Those giddy articles usually fail to mention that radius, mass and orbit are, by themselves, rather poor indicators of Earth’s potential planetary twins. What’s missing is chemistry. The visible light from distant stars — data easily acquired with modest telescopes — reveals that these celestial objects differ widely in their chemical composition. Some stars have a lot more, or a lot less, magnesium or iron or carbon than our Sun. And it’s likely that those critical differences are mirrored, at least to some extent, in the makeup of their companion planets.

Element ratios matter. Recent studies by mineralogists and geochemists (including my own research team at the Carnegie Institution of Science) suggest that even small differences in composition might render a planet inhospitable to life. If there’s too much magnesium, then plate tectonics — the engine essential to life’s cycling of nutrients — can’t get started. Too little iron, and the planet never forms a magnetic field, which is necessary to protect life from lethal cosmic rays. Too little water or carbon or nitrogen or phosphorus, and life fails.

So what are the chances of finding another Earth? With more than a dozen key chemical elements, the likelihood of replicating all the critical compositional parameters is small — perhaps only 1 in 100 or 1 in 1,000 ‘Earth-like’ planets will be compositionally similar to Earth. Nevertheless, with a conservative estimate of 1020 planets similar to Earth in radius, mass and orbit, countless worlds must be rather like our own.

And that realisation should give us pause. It’s only human to want to find planetary partners that remind us of Earth, just as we seek friends and lovers who share our tastes, our politics, our beliefs. But to stumble across someone (other than an identical twin) who is exactly like us in every respect – dresses the same, has the same profession and hobbies, uses the exact same idiosyncratic phrases and body language – would be a little creepy. In the same way, I think we’d find it disturbing to discover a clone planet.

Not to worry; it isn’t going to happen. Consider Earth’s mineralogy. Our recent research reveals that, while the Earth’s crust is packed with minerals common to any likely exoplanet, most mineral species are rare. It would be virtually impossible to replicate mineralogical details on another Earth-like planet. And if Earth’s inanimate mineralogy is unique in the cosmos, then Earth’s biology is surely even more distinctive. So, as we confidently search for ever more ‘Earth-like’ planets, we can be equally confident that there is only one Earth.

Robert Hazen

This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.