Being on the Losing Side of an Election Is More Depressing than a Terror Attack

Feeling blue this week? Chances are you’re a Democrat. I was so addled by the Republican sweep on Tuesday that I could not so much as glance at the front page of the New York Times on my Wednesday-morning train ride. (Instead, I chewed on an article about doughnuts in the Dining section.) A new Harvard Kennedy School study by Lamar Pierce, Todd Rogers and Jason Snyder, “Losing Hurts: Partisan Happiness in the 2012 Presidential Election,” tries to explain the depths of losers’ misery. Winning delivers less of a thrill than you might have imagined, and being on the losing side of an election makes you unhappier than do national tragedies like a school shooting or, yes, a terror attack.

Pierce, Rogers and Snyder came to these conclusions after inquiring into the self-reported happiness levels of Americans for several weeks both before and after three big news events in 2012 and 2013: the presidential election in November 2012, the Newtown school shooting in December of that year and the Boston Marathon bombing in April 2013.

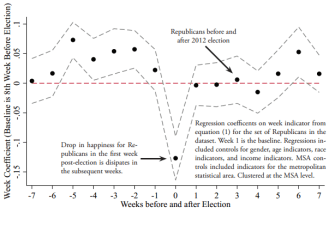

Start with the 2012 election. Republicans were initially quite glum about Mitt Romney’s loss. “We find that over the 8 weeks before and after the election,” the authors write, “happiness is relatively constant except for Republicans in the week immediately following the election. The evidence strongly suggests that Republicans experience sizable hedonic impact from the event.” (The “hedonic impact,” as you may have gathered, was a dose of melancholy.) There is a silver lining, though. Despite the hard hit to their happiness (see the figure below), Republicans “[got] over it quickly.” The V-shape of the graph suggests that political dramas do not continue to plague partisans on the losing side. In fact, the depression lasts only about a week:

Why did Republicans recover from their Obama blues so fully in the weeks after the election? People have a “tendency to adapt to bad events more quickly than they expect,” say the authors, citing previous research studies. Another plausible explanation is that only true hits to one’s life satisfaction—being fired from your job, say, or losing a close relative—will continue to hammer away at your happiness over time. Emotional responses to events with only a marginal perceived impact on your life will not trouble you for long.

So far, nothing seems too counterintutive. But the authors’ second point packs more surprise:

Both the Newtown Shootings and Marathon Bombings caused significant negative hedonic shocks, but these changes are much smaller than those suffered by partisan losers caused by the election outcome.

Even when the events are analyzed only for people likely to have stronger emotional attachments to these events—parents, for the school shooting, and Boston residents, for the marathon bombing—the phenomenon holds. For these individuals, supporting a losing candidate was still, remarkably, the more unhappiness-inducing event. “The impacts [of the school shooting and marathon bombing] are still only approximately half the size of the hedonic impact to partisan losers of losing an election.” The conclusion is striking:

[O]ne can reasonably conclude that the Republicans’ hedonic response to the election was much stronger than parents’ hedonic response to the Newtown Shootings and Bostonians’ hedonic response to the Marathon Bombings.

There are several possible reasons Republicans suffered so mightily in the immediate aftermath of the election. Maybe they thought they had a real chance of taking the White House out of Democratic hands, making the loss sting all the more. Maybe they thought Mitt Romney would save the United States from economic and moral devastation and were fearing for their children and the future of the country. But another explanation seems more plausible, and it applies equally to partisans of any stripe. Attachment to a political party constitutes an important element of many people’s individual identities and “these identities,” the authors argue, “also have important consequences to people’s hedonic lives.”

When your candidate loses, it’s a slap in the face not only to the candidate or to your party but to you. Many studies have shown how profoundly partisanship filters into our subconscious and colors our judgment. One recent piece of research suggests that “partyism” is now a stronger source of prejudice than racism. Yet the speed with which most of us recover from post-Election Day doldrums suggests that the emotional hit has more to do with our conceptions of ourselves than with our honest appraisal of how much worse things will actually get under new political leadership. So, three days after the election, it’s almost time for bereaved Democrats to bravely read the front page again. We’re just two short years away from another election-induced hedonic impact of one sort or another.

image credit: Shutterstock.com