Human brains can recover after flatlining, study suggests

When a person’s brain activity flatlines, it doesn’t always mean the damage is irreversible, suggests a new paper published in Annals of Neurology.

The paper outlines the first-ever observations of a phenomenon that occurs as the brain begins to die, and the findings could help medical professionals better determine when someone has officially died, and possibly change organ donation protocols.

In the study, researchers monitored the electrical signals in the brains of nine patients who had suffered serious brain injuries. The patients had “do not resuscitate” orders in effect, had already been outfitted with the brain-monitoring electrodes before the researchers got involved, and were set to have their life-support systems terminated.

The goal was to learn about the sequence of electrochemical events that occur in the brain during the minutes preceding death. Science can already describe much about this process.

Neurons, the basic building block cells of the nervous system, are able to send signals because they contain charged ions that create electrical imbalances between themselves and their surroundings. But when the heart stops and blood ceases to flow, these cells lose the oxygen they need to survive. This emergency situation causes the cells to draw on fuel reserves.

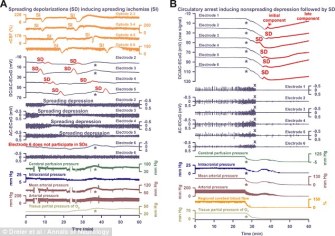

Then, the neurons go “silent” in an effort to conserve energy, resulting in a “wave of darkness” that occurs all at once. What’s happening, as Rafi Letzter at Live Science writes, is that the brain cells are using the “energy stores to maintain their internal charges, waiting for the return of a blood flow that will never come.”

This phase, known as depolarization, is short-lived.

“Within about three minutes the brain’s fuel reserves have become depleted,” lead study author Jens Dreier, a professor at the Center for Stroke Research Berlin, told Newsweek in an email.

It’s around this point in the process that brain activity flatlines, and researchers previously thought that this marked irreversible brain damage. However, that might not be the case.

“That’s really the fundamental insight here,” Jed Hartings, a neuroscientist at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and a member of the UC Gardner Neuroscience, told Newsweek.

The researchers observed that, as has been shown in previous experiments with animals, the brain undergoes a second “wave of darkness” that, unlike the first wave, spreads more slowly as cells run out of fuel reserves. Brain damage could still be reversible shortly after this second wave begins, but minutes after that could represent a more accurate marker of irreversible brain damage, or brain death itself.

The findings could affect protocols surrounding organ donation. Currently, some protocols allow surgeons to begin removing organs from people just five minutes after their heart stops beating. That might be way too soon.

“The nerve cells are not dead at five minutes,” Dreier told Newsweek, citing experiments done with animals. He added that it’s very likely a person will recover if their circulation resumes after five minutes.