The Atir-Rosenzweig-Dunning Effect: when experts claim to know the unknowable

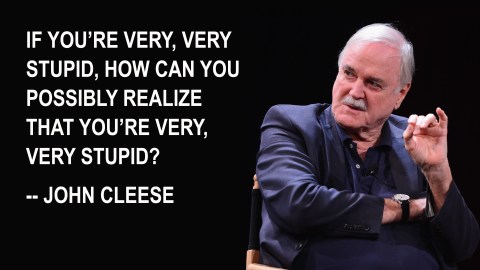

Remember the Dunning-Kruger Effect? The finding by David Dunning and Justin Kruger that incompetence leads to inflated beliefs of competence. If you need a refresher, the concept is succinctly explained below by John Cleese:

.

Dunning has now conducted a new study with colleagues Stav Atir and Emily Rosenzweig, finding that expertise has its own pitfalls. In a series of experiments conducted at Cornell University, the researchers found that people with greater knowledge in a particular domain were more likely to claim knowledge that they could not possibly know.

The researchers first asked the participants to rate their expertise in a particular area, personal finance for example, before being asked to rate their knowledge of a variety of specialist terms, some of which do not really exist, such as “pre-rated stocks, fixed-rate deduction and annualized credit.” The higher the people rated their own expertise in a particular area, the more likely the people were to claim to know all about the nonsense terms made up by the researchers.

But astoundingly the effect wasn’t limited to self-professed expertise. A follow-up experiment found that when tested on their knowledge of terms in a specific domain, the participants’ success really was correlated with overclaiming. A possible explanation for this finding is that the participants with a greater vocabulary in a particular domain were more prone to falsely feeling familiar with nonsense terms in that domain because of the fact that they had simply come across more similar-sounding terms in their lives, providing more material for potential confusion. The finding does somewhat call into question the popular idea drawn from Dunning’s earlier research that expertise invariably leads to a clearer picture of both what we do know and what we don’t know; perhaps in some ways as we learn more, we find that our knowledge of what we don’t know becomes blurred in the process.

Interestingly, the easier the test was in terms of easily recognisable words, the more likely the people were to overclaim knowledge of nonexistent concepts, suggesting that the feeling of mastering a domain is all that is needed to make us claim we know more than we really do.

Another particularly interesting finding was that even when participants were warned that some of the statements were false, the “experts” were just as likely as before to claim to know the nonsense statements, while most of the other participants became more likely in this scenario to admit they’d never heard of them.

One burning question the researchers didn’t speculate on is examples of where this effect may occur in the real world. I couldn’t help but be reminded of Baroness Susan Greenfield, a British neuroscientist who has been broadly pilloried by her peers in the field for making bold and controversial claims in the media about the harmful effects of technology without citing relevant evidence, or publishing any peer-reviewed work on the subject.

But before you begin to gloat in the benefits of ignorance, you should be aware that it seems most of us are actually vulnerable to this phenomenon. A stunning 92 percent of people claimed to be familiar with the nonexistent biological subjects of “meta-toxins,” “bio-sexual,” and “retroplex.” This research doesn’t necessarily challenge the original Dunning-Kruger Effect, but it does add the caveat that when it comes to knowing what we don’t know, in some specific circumstances expertise can be even more blinding than ignorance itself.

Follow Simon Oxenham @Neurobonkers on Twitter, Facebook, RSS or join the mailing list. Image Credit: Shutterstock

Reference:

Atir, S., Rosenzweig, E., & Dunning, D. (2015). When Knowledge Knows No Bounds Self-Perceived Expertise Predicts Claims of Impossible Knowledge.Psychological science, 26(8), 1295-1303. (PDF)