The Genes for White Skin Didn’t Develop in Europe, UPenn Study Finds

I’m a cat owner. I marvel at Selena’s agility and shake my head at the inanities of her behavior, like not allowing me to go to the bathroom for five minutes by myself. If I shut her out, she meows at the door. The truth is, there’s only about a 10% genetic difference between me and her. That’s mind-blowing, considering that there are 3 billion base pairs in the human genetic code.

Between humans and chimpanzees, the genetic difference is only 4%. From one human to the next, it’s minute, just 0.1%. Now, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, have a better grasp on the science behind race and why we have different skin tones. The results were published in the journal Science.

We actually know very little about the genetics behind race. Although we may think of Africans as all having a similar pigmentation, there’s a wide variety of skin tones on the continent. Some studies have isolated a few genes responsible for skin color. Yet, these were only identified among white populations, until now.

A collage of people included in the study. Credit: Alessia Ranciaro and Simon Thompson. The University of Pennsylvania.

Looking at genomes from different populations all over the African continent, researchers found the genetic variants responsible for skin pigmentation namely: SLC24A5, MFSD12, DDB1, TMEM138, OCA2, and HERC2. Geneticist Sarah Tishkoff was the senior author on this study. She said that in their paper, she and colleagues “show that mutations influencing light and dark skin have been around for a long time, since before the origin of modern humans.”

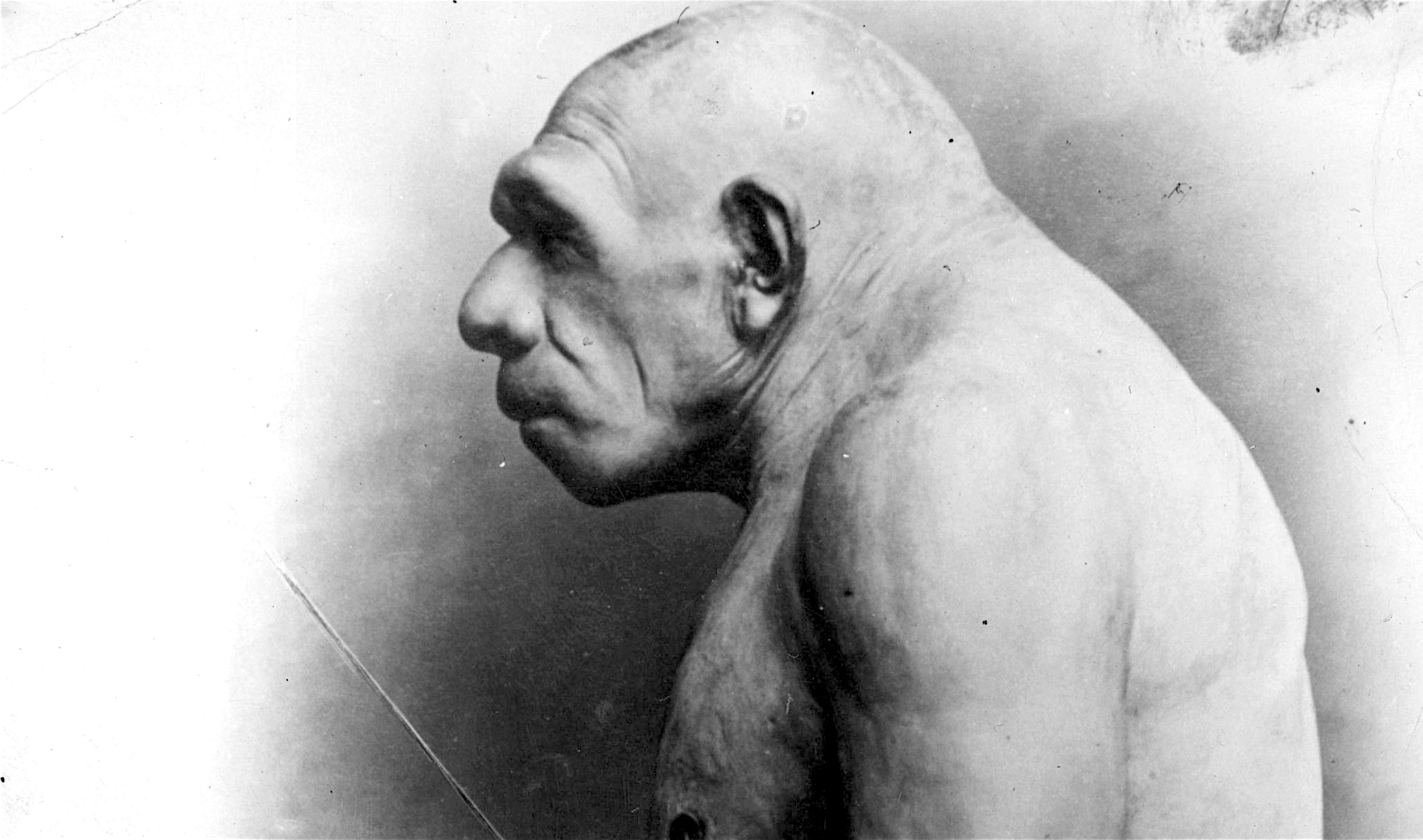

Our ancient ancestor Australopithecus, which lived in Eastern Africa between 3.85 and 2.95 million years ago, probably had light skin underneath dark fur. Chimps, one of our closest living relatives, are the same way. Since their fur protects them from the sun, there’s no need for more melanin.

At some point, an ancestor of ours was born without all that tremendous body hair. It was thought that shortly after, this hominin developed dark skin to protect it against harsh UV rays. So our oldest hairless ancestor may have had white skin, but only for a brief period.

Model of Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis). Credit: Getty Images.

Tishkoff and colleagues took a color meter and used it to reflect the light off the skin of over 2,000 Africans. Those with the lightest skin tone were the San people of southern Africa. While the darkest tone was found among the Nilo-Saharan pastoralists of eastern Africa, particularly the Mursi and Surma peoples.

Researchers collected genetic material from 1,570 Africans. They studied their genomes, examining 4 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in all. These are areas along the genome where a gene has been altered. From there, they identified the four key areas responsible for the variation in skin pigmentation. What surprised researchers most was that the gene SLC24A5—responsible for light skin, thought to have developed in Europe, is actually very common in Africa.

Genes HERC2 and OCA2, a close neighbor of SLC24A5, is associated with light eyes and skin. It was found common among the San, bearers of humanity’s oldest genetic lineages. But this gene is also associated with a condition called vitiligo, which is where a depigmentation occurs on certain areas of the skin. This was an exciting find for the team. It gave greater weight to their findings.

The genes for light skin can be found not only in Europe and Africa, but Southeast Asia and the Middle East as well. “Most predate modern humans,” Tishkoff said. “They’ve been variable for tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of years in Africa. Everyone had the alleles for light skin.”

San children. Credit: Nicolas M. Perrault. Wikimedia Commons.

The prevailing story of human migration is that modern humans traveled out of Africa somewhere between 80,000 and 60,000 years ago, reached Asia and later on, advanced into Astralo-Melanesia. Then, a second wave populated other regions of Eurasia.

According to Dr. Tishkoff, as a result of this study, “it is also possible that there was a single African source population that contained genetic variants associated with both light and dark skin and that the variants associated with dark pigmentation were maintained only in South Asians and Australo-Melanesians and lost in other Eurasians due to natural selection.”

Those areas of highest ultraviolet intensity are where populations seem to have darker skin tones. Also, Africans are far less likely to develop melanoma. The researchers also identified gene variants for dark skin in south Asian Indian and Australo-Melanesian populations. Outside of Africa, these groups are the most likely to have dark skin. They had the same genes as dark-skinned Africans. So dark-skinned populations may have naturally selected for darker skin in regions where it’s advantageous for survival, whereas Europeans did the same for lighter skin, since it allowed them to absorb more vitamin D.

To learn more about race from a genetic point of view, click here: