When It Comes to Neanderthals, Humans May Be the Borg

Editor’s Note: This article was provided by our partner, RealClearScience. The original is here.

In 1856, a group of quarrymen discovered the remnants of a strange skeleton in Germany’s lush Neander Valley. They thought it was a bear. They were wrong. In fact, the quarrymen had unearthed the first scientifically recognized remains of Homo neanderthalensis, an ancient human ancestor.

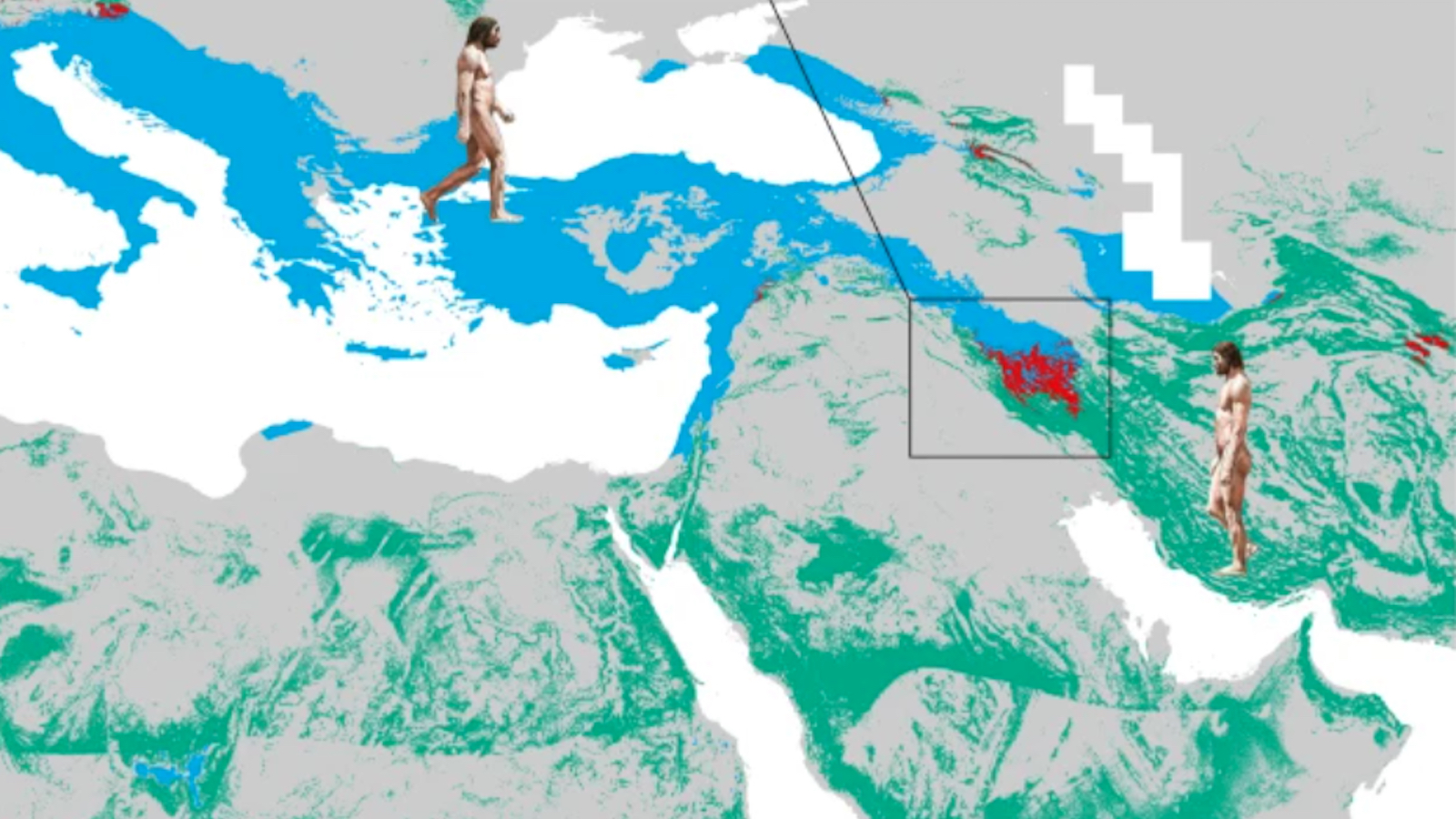

Colloquially known as Neanderthals, the species quickly became synonymous with the prototypical “cavemen,” you know, the grunting, apish type. Stocky, bigheaded, and wide-nosed, they fit that brutish description well. Neanderthals’ simpleton status also made it intuitively clear why they died out: they were plainly inferior to humans, so when Neanderthals and Homo sapiens — humans — began cohabitating the same regions of Europe and the Middle East around 50,000 years ago, humans either outcompeted them or actively hunted them to extinction.

In the past few decades, however, anthropological discoveries have contradicted those stereotypical views. Neanderthals actually had slightly larger brains than modern humans! Moreover, they were accomplished big game hunters, crafted advanced tools, ritualistically buried their dead, and utilized language and symbols.

According to archaeologists Paola Villa and Wil Roebroeks, these recent discoveries counter the notion that human superiority somehow led to the demise of the Neanderthals. They state their case in the form of a systematic review of archaeological records, published in the online open-access journal PLoS ONE.

The extinction and competition hypotheses for the demise of the Neanderthals, notably suggested by interdisciplinary scientist and author Jared Diamond, hinge on the idea that humans were more advanced than Neanderthals. Commonly claimed are the following: that humans had more communicative abilities, were more efficient hunters, had superior weaponry, ate a broader diet, and had more extensive social networks.

But the archaeological record doesn’t back any of those claims, the authors found.

“The results of our study imply that single-factor explanations for the disappearance of the Neanderthals are not warranted any more,” the duo writes.

Villa and Roebroeks’ findings raise an intriguing question: If Neanderthals weren’t driven to extinction, well, then, where did they go?

According to Villa and Roebroeks, the best explanation now is familiar to anyone who’s acquainted with the Borg, a ruthless collective of cybernetic beings from Star Trek. Neanderthals were assimilated… by us. That’s right: Humanity is the Borg.

In 2010, scientists discovered that between one and four percent of the DNA of modern humans living outside of Africa is derived from Neanderthals, providing clear evidence that the two species were interbreeding to some extent tens of thousands of years ago. In January of this year, Benjamin Vernot and Joshua Akey of the University of Washington published a paper in Science that corroborated those results. They found that a fifth of Neanderthals’ genetic code lives on within our species as a whole.

While interbreeding may be the leading explanation for the demise of the Neanderthals today, it may not be tomorrow. There are few topics in science more convoluted than human evolution. But when it comes to unearthing our past, our curiosity compels us to keep digging.

Resistance, after all, is futile.

(Images: AP, Paramount Pictures)