Why Winners Are Geniuses and Losers Are Dolts

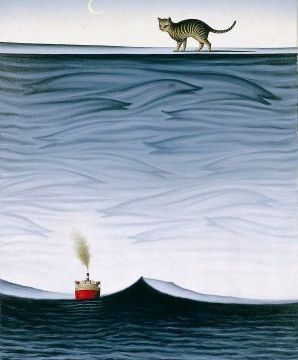

Being a social animal saves you a lot of trouble. You don’t need to grow huge claws or massive armored plates to protect yourself; your weapons and your shield are in your relationships to other members of your pack.

In many bird species, a flock will “mob” a predator. And in Alaska I’ve seen musk oxen form a circle, horns out and tails in, because we were flying over in a small plane; their group bond assured that each individual was better protected (and helping to protect others) from the threat. If our plane had been forced down we human beings would have radioed for help from other people. Those are all examples of mutual protection based on social bonds.

Still, there’s a downside to storing your weapons in the minds of other people: If your social standing changes, then pffft, no more protection for you. Worse yet, social ties can turn against you: Lions’ claws don’t suddenly attack their owners, but animals that live in flocks or packs sometimes turn on one of their members.

The ethologist Irenaus Eibl-Eibesfelt once proposed that human laughter has its roots in mobbing: “Many apes and monkeys that live in groups show their teeth when they do this and emit rhythmic threat sounds. Both these elements are still retained in our laughter and there is no doubt that it is often very aggressively motivated,” he wrote. “The person who is laughed at experiences the laughter as aggressive. But the people who are laughing together feel themselves to be bound together via this ritualized `mobbing.’ ”

Which brings me to my colleagues in journalism.

As Mark Bernstein pointed out in this witty post, in the business press “CEO’s of winning firms are brilliant (and handsome), while the leaders of losing firms are incredible dolts — pursuing obviously-doomed strategies, saying dumb things, and lacking the personal qualities that distinguish winners.”

The media pattern is the same in matters military and political, obviously. At some point, your everyday mistakes and little offenses are no longer like everyone else’s — instead, they’re grounds for universal contempt. Entertainers complain the most about this phenomenon, but they at least have their last-ditch loyal defenders. Nobody ever begged the world to “leave Mark Penn alone!”

So, what makes a band of people turn on one of their own? Bernstein thinks it’s built in to the logic of attention. A mistake could be the reason that you’re losing your battle, so naturally you’ll pay attention to it. On the other hand, if you’re winning, then the exact same behavior doesn’t get that anxious scrutiny. How serious a mistake can that be, if we’re winning?

It’s an interesting idea, and distinct from the usual thinking about why we build leaders up and then tear them down. Perhaps we’re innately biased to be too forgiving when our luck is good, and too harsh when it’s bad.