Will Neuroscience Kill the Novel?

Virginia Woolf once wrote that “human character changed on or around December, 1910.” It’s a deliberately cryptic remark, but she was referring broadly to the wave of cultural modernism that blasted the complacent world of late nineteenth-century Europe into the fractured cosmos of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, and World War I.

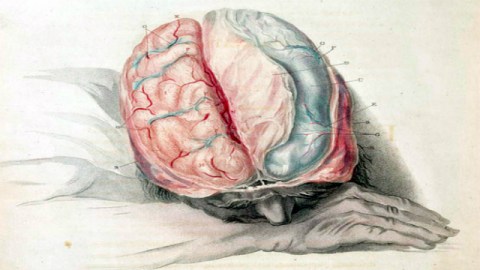

I thought of Woolf’s pronouncement last December, when I read this New York Times article about neuroscientists’ quest to map the human brain in its entirety. The project is only the latest to signal a scientific revolution in our understanding of the self—one that puts Freud’s essentially literary revolution to shame. A century after Woolf’s epochal moment, I wonder if we’re witnessing an even greater cultural watershed.

The implications stagger the mind, or at least engorge the frontal lobe. How will a deterministic, neurological account of motivation change our notions of “guilt” or “innocence” before the law? How will a precise grasp of the neurobiology of attraction affect human mating patterns? (I can’t wait for that pharmaceutical arms race.) And most compelling from Woolf’s perspective: how will knowing our own brains so well change literature?

All fiction has at its heart the enigma of character. Its most basic pleasures involve analyzing how human beings act, speculating as to what motivates their actions, and, ultimately, judging those actions. What happens if science largely co-opts the first two projects, and undermines the legitimacy of the third?

In a 2009 n + 1 article, “Rise of the Neuronovel,” Marco Roth called neuroscience a “specter…haunting the contemporary novel.” Roth charts the two-decade-long surge of neurological references in the work of such authors as Jonathan Lethem, Richard Powers, and Ian McEwan. The trend has given us a slew of neurologically abnormal characters, and even a neurosurgeon narrator in McEwan’s Saturday. It’s also brought an increase in sentences like these: “‘Oh,’ I said, my palms beginning to sweat as random sensuality carbonated up to my cortex.”

Roth skillfully argues that the neuronovel has begun supplanting the psychological novel. Characters (and authors) who once thought in terms of neuroses and libidos now speak of glial cells and synapses and serotoninlevels. Dr. Perowne in Saturday is the modern analogue for psychologist Dick Diver in Tender Is the Night: both come to us as ambassadors from the latest science of mind. And yet where Freud’s discipline always carried a strong whiff of myth, neuroscience is orders of magnitude more complex and precise. Roth’s conclusion is that we now confront “the loss of the self,” and that “the neuronovel, which looks on the face of it to expand the writ of literature, appears as another sign of the novel’s diminishing purview.”

Poignant as this is, I think it overstates the case. The novel will survive, though some of the current vocabulary surrounding it—critical and metaphysical—probably won’t.

Much as evolutionary psychology has drained some of the mystery from collective human nature—helping to explain, for example, why humans instinctively form hierarchies, or why the sexes differ on average in their attitudes toward sex—neuropsychology will drain some of the mystery from individual human personality. And where understanding improves, tempered judgments may follow. I believe it actually will become harder to speak of Faulkner’s Jason Compson as “evil” in a metaphysical sense—or as a raging but thwarted id, or an instrument of repressive patriarchy—rather than positing some kind of defect in his orbitofrontal cortex. The latter description will become the literal one, while the others shade back further into metaphor.

At the same time, I think subjectivity will always be first and foremost the province of art. Explaining a subjective state isn’t the same thing as expressing it. A neurologist may be able to tell you exactly what’s happening in his brain when he stares at autumn leaves, but he’s unlikely to describe them as “yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,” as Percy Shelley did. And of course, to understand one’s own brain in exquisite detail isn’t necessarily to have the means or will to change it. That means human tragedy and comedy won’t be disappearing anytime soon. (Neither will irony. Does anyone doubt that as our knowledge of the brain increases, we’ll find some incredibly stupid ways to use it?)

Neuroliterature suffered a famous real-life tragedy three years ago, when David Foster Wallace—who probed the human mind in the most up-to-date scientific terms available—succumbed to suicidal depression. His example is a terrible reminder that neither we nor our drugs know everything yet. As long as that’s true, the novel will have its niche.

And who knows what forms it will take? We might see fiction starring the neuro-era equivalent of Hamlet (or Alex Portnoy), paralyzed by detailed awareness of his every mental process. We might also see a backlash in the other direction: a New Opacity favoring third person limited narration, and emphasizing everything we still can’t understand about each other. Most likely we’ll see versions of both, plus a dozen other new schools. Regardless, neurology won’t discourage us from self-contemplation any more than astrophysics keeps us from gazing at the stars. A glut of the literal only sharpens our appetite for the metaphorical: “human kind / Cannot bear very much reality,” as T. S. Eliot put it. The day the brain is fully mapped, writers will find a way to turn it into a foreign country.

[Image courtesy Flickr Creative Commons, user brain_blogger.]