Codex v. Vizplex

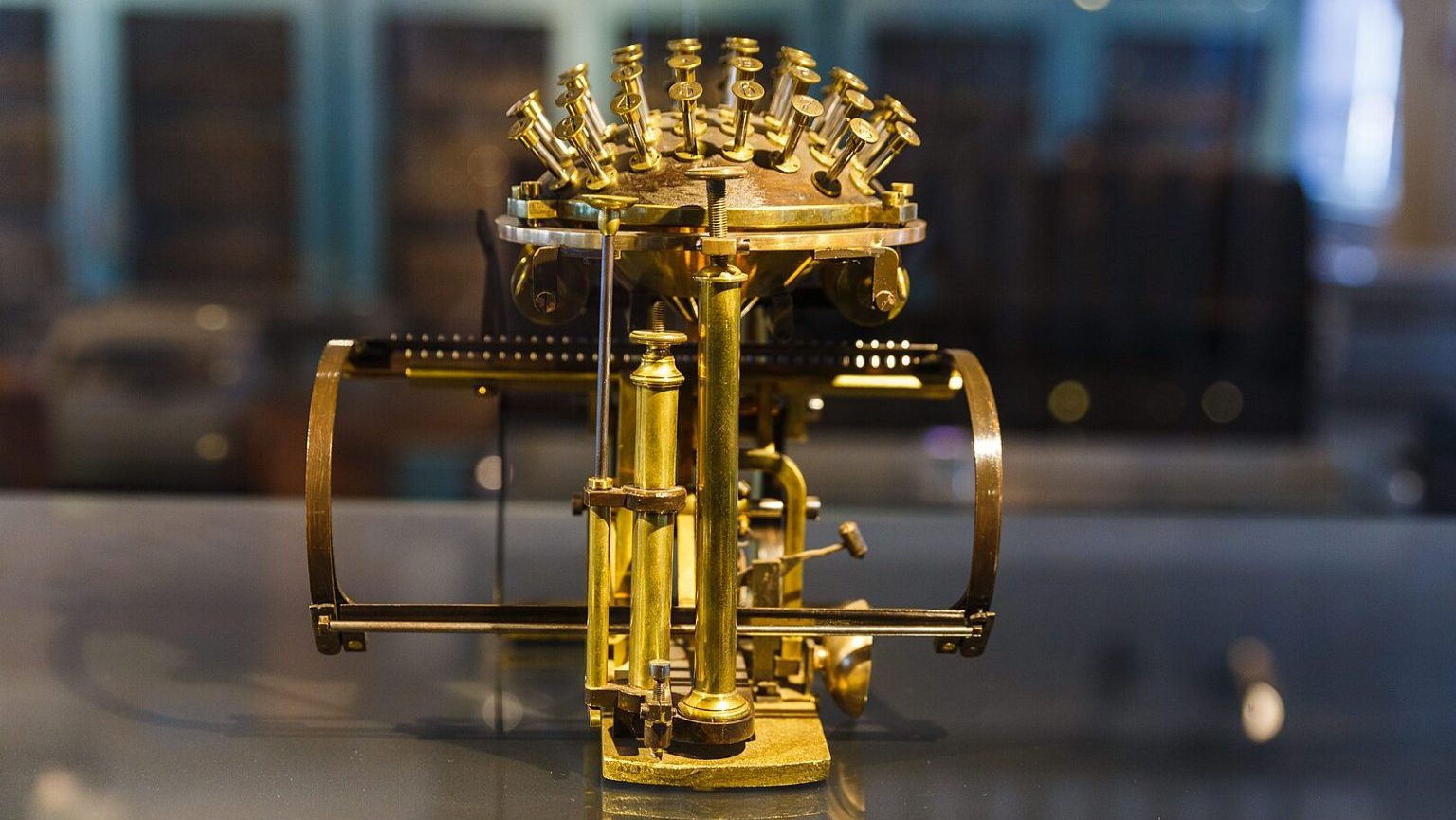

No, I’m not promoting a fight between two futuristic boxers. I’m talking about the publishing industry and how Sunday afternoons of the future will be spent. Will Gutenberg’s printing press go the way of the telegraph, or is Kindle the New Coke of publishing? In one corner is Codex, the traditional ink on paper format, while in the other corner is Vizplex, the microsphere screen you read from if you have been eager enough to buy Amazon’s Kindle (2). The information revolution is well underway, but will the book as we know it really be a thing of the past?

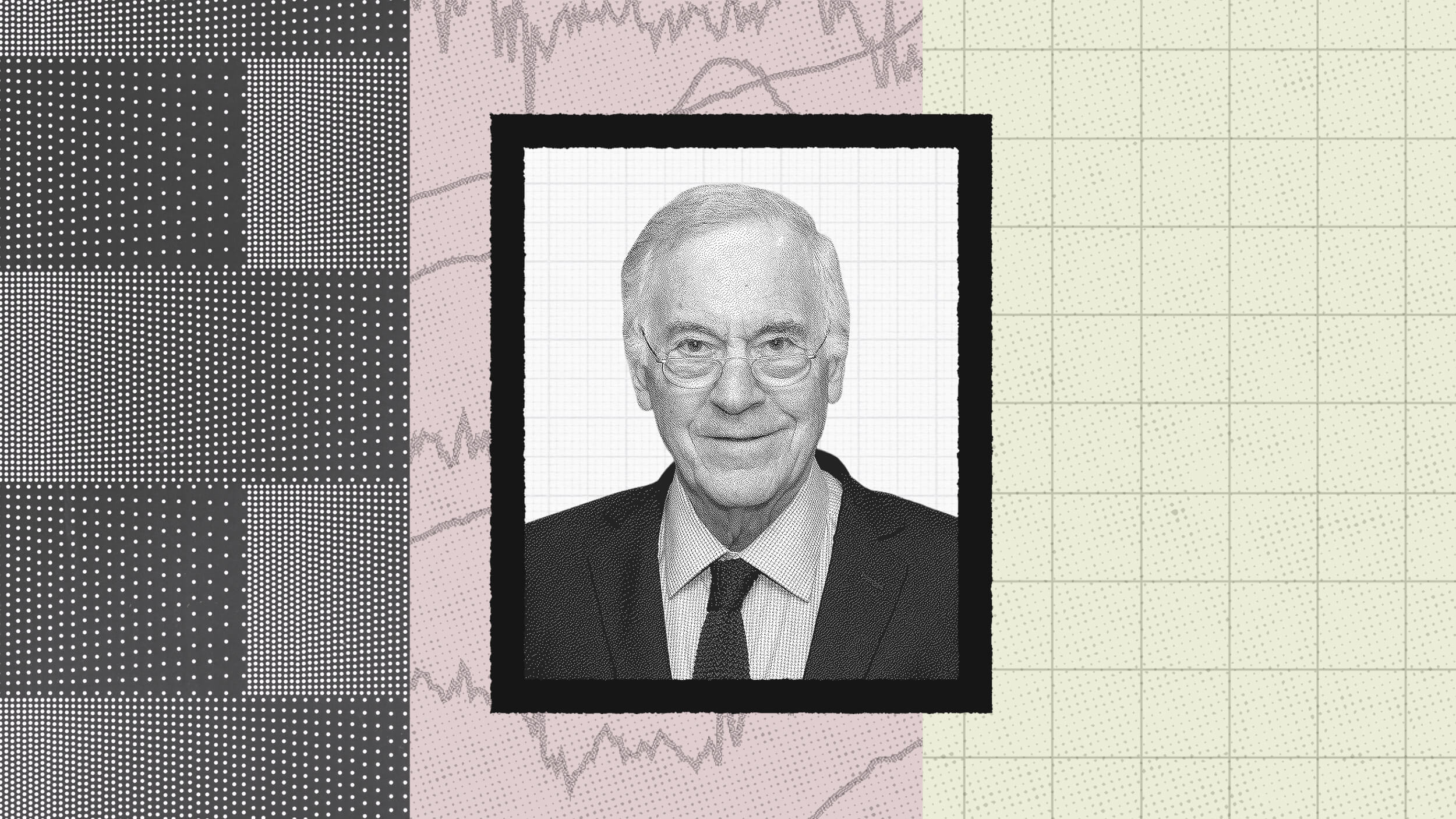

Different points of view yield different predictions, but few people, if any, think current technologies have delivered the K.O. to perhaps the cultural heavy weight: the book. Still, the digital revolution can’t help but influence the way people have read ever since Gutenberg’s vision was fully realized. Jason Epstein, who as the founder of the New York Review of Books has led a very innovative publishing career, sees certain information as no longer useful in codex form. In an insightful 2009 speech, he said ephemeral information like almanacs will be the first to abandon the book format since they are literally out of date as soon as they are published.

Bill Wasik, editor at Harper’s Magazine and Big Thinker himself, thinks the book will survive as an oasis to the pressures of a 24/7 media environment. He predicts the printed page will remain the preferred format for more in-depth ideas, and reliable and thoughtful content.

The American public, at once fickle and unpredictable, has ignored (cheaper) reading devices such as Sony’s Reader, which allows users to access all the public domain books Goolge has digitized. Instead, the people have fallen behind Amazon’s Kindle, which tends to offer more romance titles than classics because, well, that’s what the majority of readers are after.

Another theme touched on by Epstein is the same trend among booksellers who, during the great American suburb migration, placed themselves in shopping malls between Footlocker and Sbarro. Faced with steep rent prices and inventory constraints, they opted for best-sellers over less ephemeral literature. The same thing is currently happening to the long treasured independent used book shops of England. But the digitization of print media removes both rent and inventory from the equation. Content goes directly from the publisher to the consumer. But then where does it go?

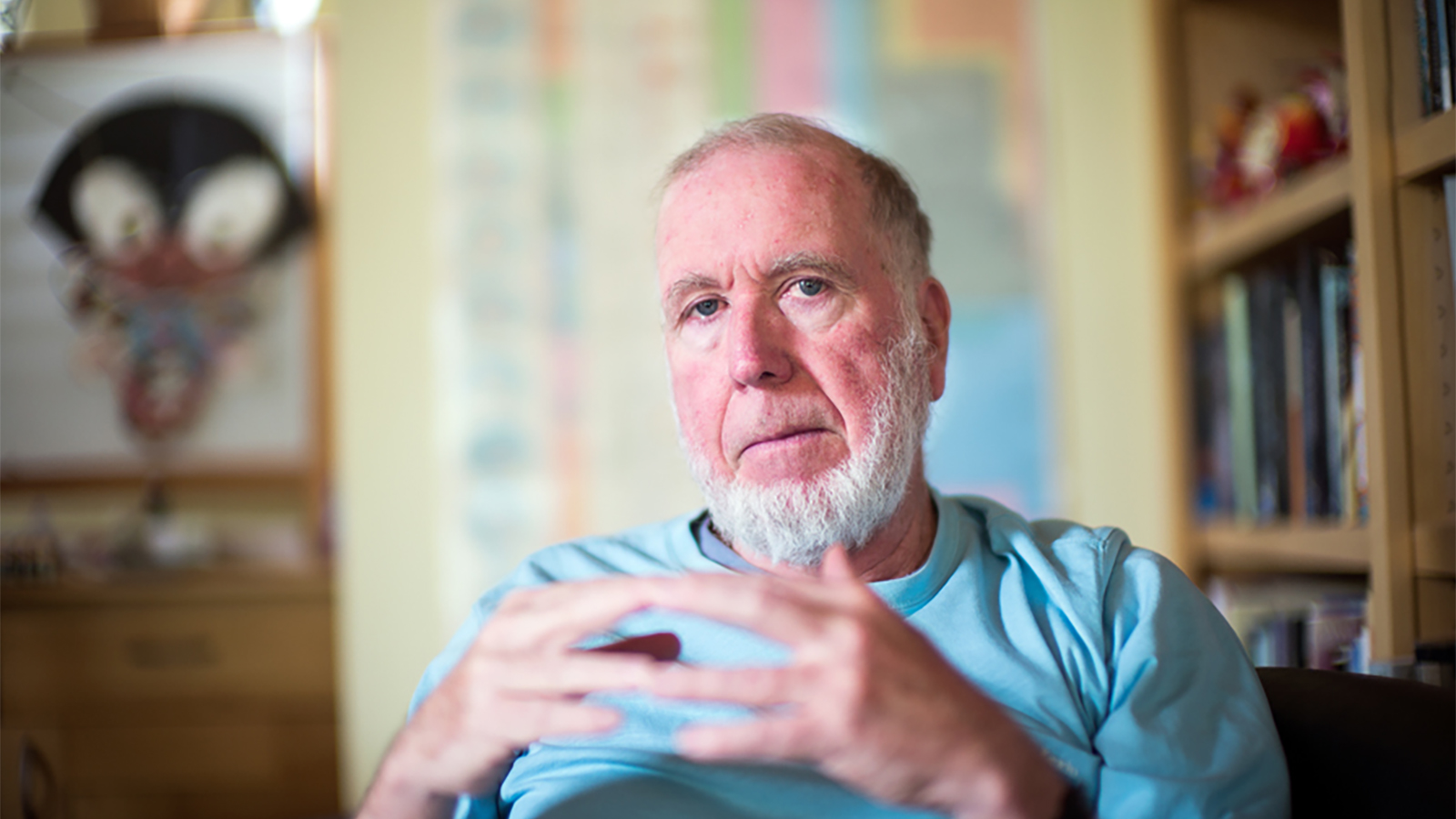

Nicholson Baker writes for the New Yorker that, “Kindle books aren’t transferable. You can’t give them away or lend them or sell them. You can’t print them. They are closed clumps of digital code that only one purchaser can own. A copy of the Kindle book dies with its possessor.” Ironically, until featherweight digital reading devices become more like their seasoned heavyweight predecessor, the book will stay off the ropes and keep its very literal staying power.