Davos experts warn about future “rogue technology”

At the recently concluded annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, that brought together world leaders and top thinkers in different fields, a panel on the dangers of emerging technology raised some strong alarms.

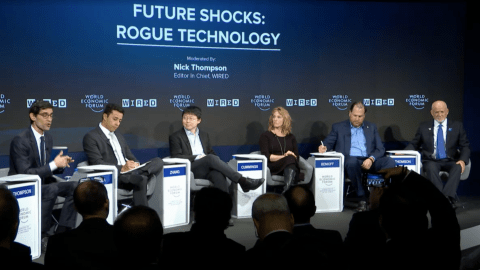

The January 25th panel “Future Shocks: Rogue Technology” featured the chairman and CEO of Salesforce Marc R. Benioff, the director of Duke University’s Humans and Autonomy Lab Mary Cummings, the MIT professor of neuroscience and creator of CRISPR Feng Zhang, Brazil’s Secretary of Innovation Marcos Souza, as well as Peter Thomson, the UN Special Envoy for the Ocean. The event was moderated by Nick Thompson, Wired Magazine’s Editor-in-Chief.

What technologies of the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution are the most exciting and potentially risky? The discussion focused on AI, robotics, and bioengineering.

One innovation Marc Benioff would like to see in the near future are beach-cleaning robots. They could help the environment by making a dent in the “growing problem of plastics in the oceans,” according to Benioff. This same tech can also be adopted into creating autonomous deep-sea robots that mine the ocean’s floor for valuable metals and other materials. One drawback to this tech – there are currently no laws regulating it.

UN’s Peter Thomson agreed that the ocean is the next frontier for exploration that needs a legal framework.

“We know more about the face of Mars than the ocean floor,“ said Thomson. “Seabed mining is definitely coming but it’s not allowed at present. We don’t have regulation, but laws will be ready soon.”

The one government rep on the panel, Brazil’s Souza, acknowledged that lawmakers need to step up because of the sheer speed of technological advancements.

“The characteristic of this fourth industrial revolution is the speed of the technology advancing and, as you know, the government regulation is always behind this […] speed, so it’s a challenge for us,” said Souza. The previous revolutions took longer so we could prepare those regulations properly, but this is going too fast.”

Professor Cummings from Duke leads a tech lab but says “technology is not a panacea”. She thinks we often overestimate what it can do. She is anxious that the tech created for one useful task will acquire a more detrimental purpose in somebody else’s hands – driverless cars or drones can be hijacked, gene editing could lead to eliminating some species. She is also not sure that “a beach-cleaning Roomba robot” is a good idea.

“My concern with deep-sea mining robots is not the intentional malevolent use of technology, it’s the accidental malevolent use,” said Cummings. “AI is definitely opening up a Pandora’s Box. Most applications of AI, particularly when it comes to autonomous vehicles, we do not understand how the algorithms work.”

Cummings is also concerned that some of the technology being developed will be employed before proper testing. She thinks more oversight is needed to figure out which innovations are ready to be used widely and which ones need more development.

“As a researcher, what I worry about is [that] we’re still finding about the emergent properties of these technologies – CRISPR, AI – yet there are many companies and agencies that want to take these technologies and start deploying them in the real world, but it’s still so nascent that we’re not really sure what we’re doing,” explained Cummings. “I do think [there] needs to be more of a collaborative arrangement between academics and government and companies to understand what’s really mature and what’s very experimental.”

MIT’s Professor Zhang, a pioneer of using the gene-editing technique CRISPR, also admonished that we need to take baby steps with some advancements, especially when it comes to altering life’s building blocks.

“When we’re engineering organisms,” said Professor Zhang, ”I think we have to be very careful and proceed with a lot of caution.”

He also thinks it incumbent upon researchers to create “containment mechanisms” that can curb the spread of a technology that turns out to be dangerous after its implementation.

On the other hand, he is excited about the possibility of transferring traits from one organism to another, something he’s working on in his lab. This can help resurrect or protect some species.

“As we sequence more and more organisms, we can now find interesting properties that these organisms evolved to allow them to most optimally survive in their own environment and transfer some of those into other organisms so that we can improve the property…and prevent the extinction of species,” said Zhang.

Saleforce’s Marc Benioff used an example from his own company to illustrate why technology needs to mature before being spread.

“As a CEO I can ask a question of [Salesforce] Einstein, my virtual management team member, and say ‘how is the company doing’, ‘are we going to make our quarter’, ‘how is this product’, ‘what geography should I travel to and have the biggest impact for the company’, said Benioff. “I have this kind of technology, and I want to make it available to all customers. But I don’t want to turn it over and get a call from a CEO that he or she made a bad decision because we didn’t have it exactly right yet.”

One more obstacle to the testing and fast implementation of technology – lack of educated talent that can develop it, said Cummings. She called out a “global AI crisis for talent” as detrimental, with universities unable to graduate enough people for the burgeoning field, while the education model, in general, is woefully “archaic”. Students are still being trained like they were 30 years ago, warned the professor.

You can watch the full panel here: