How will virtual reality change your mind’s consciousness?

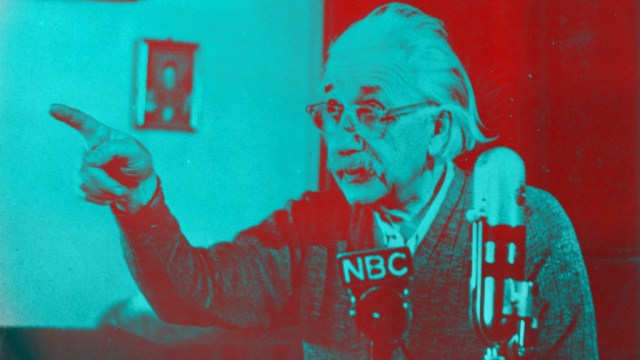

Over a half-century ago, Canadian professor and philosopher Marshall McLuhan wrote one of the most influential books on media theory ever. Understanding Media introduced a number of ideas and phrases that now seem commonplace: “hot” and “cool” media; global village; and, of course, “the medium is the message.” He is credited with predicting the emergence of the World Wide Web three decades before its invention.

In McLuhan’s understanding, the terms medium, technology, and media are interchangeable. The subtitle of his book, The Extensions of Man, posits that any technology (and therefore medium and media) is effectively an extension of our bodies and consciousness. When I’m driving, the car is an extension of myself: its boundaries are now my own; my awareness must now take its full size and power into consideration.

This also includes smartphones, in which people walk around unaware of their environmental boundaries because their consciousness has been subsumed by a device. Where the technology ends and “I” begin becomes hazy. According to McLuhan, there is essentially no such distance. The content of the medium is not nearly as important as the medium itself, for it is the medium that changes societies, much more so than any specific content.

In some ways, the content can even distract us. Facebook is a fitting example. As McLuhan writes, “the ‘content’ of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium.” We might assume technology is always progressing, but that’s not necessarily the case. Notice the other term he assigns to our creations:

Any invention or technology is an extension or self-amputation of our physical bodies, and such extension also demands new ratios or new equilibriums among the other organs and extensions of the body.

GPS is a wonderful technology, but it comes at a cost. Its long-term effect on our memory and visual systems force us to confront its true value. Studies have shown that the more you use maps, the smaller your hippocampus, your brain’s memory center. You are now the only landmark, which is quite useless if you have no idea where you actually are. Don’t misunderstand: using GPS to find your way around new territories is a wonderful advancement. Continual reliance on it in the same neighborhoods is another story.

You are already a cyborg

Technologies don’t necessarily make us useless, however. If anything, the opposite: philosopher and cognitive scientist Andy Clark believes we are all cyborgs, “in the most natural way.” We are what we are as animals thanks to our environment and the technologies we’ve created to engage with it. This is as true for the Uber driver and GPS as the wheelchair-bound and ramps. Our technologies define our realities, as Clark expressed when co-writing a famous paper (with Australian philosopher Dave Chalmers) that expanded the definition of “mind” beyond the body.

A gamer wearing virtual reality (VR) goggles plays a game at a newly-opened VR park at The Dubai Mall on March 6, 2018. (Photo by Giuseppe Cacace/AFP/Getty Images)

While Clark appears more optimistic about mediums than McLuhan, he recognizes the dark side of, say, algorithms, and the invasion of privacy. Yet overall he feels that such “radical honesty” promotes liberalism and democracy—a theory being tested in the age of social media. Essentially, he’s saying you should be able to defend the reality you’ve constructed. The problem is, at least in digital space, we’re not always engaging with an environment whose boundaries we understand, making us vulnerable in a way we’ve never quite experienced.

Clark’s theory of “extended mind” and McLuhan’s media extensions remind us that consciousness is not confined to the body. There need not be any mysticism to this. As journalist Michael Pollan argues in his forthcoming book on psychedelics, if any of us were to experience another person’s mental state it would likely feel like a psychedelic trip, given how foreign the sensations and observations would be.

How will virtual reality change this?

In a sense, we’ve been living in virtual reality as long as we’ve been human beings. The constructs of consciousness demand that our observations and memories inform the reality we create. I can empathize with ideas foreign to me, but I can’t truly understand them. It’s unlikely I’ll consider their potential for inclusion in my comprehension of reality. Debates over facts or “fake news” aside, I live in a very different construct than a Trump supporter. Our ideas on a great many things are divergent.

Yet I share a great many ideas with the Trump supporters I am friends with. When together we rarely discuss politics, but even when we do, our conversations are never belligerent. When occupying the same physical space we are bound together by a shared experience of environment. Trump supporters (or trolls) that have commented on my social media handles are not nearly so kind. With no shared environment, it’s easy to forgo humanity because at that moment your only environment is you.

You need not be physically removed from someone to understand how important environment is. Simply observe the next person you follow that’s staring at their phone. They never walk in straight lines; their cadence is off; they often stop randomly and bump into objects or people. When reality—the shared reality we occupy in a social space—snaps them back to attention, you can recognize the attentional lag in their eyes, at least for the brief moment before they return to their phones.

The society we inhabit affords certain luxuries, such as not having to always pay attention, but is this really a valuable trade-off? As of now, the virtual realities we enter are constructed by other minds. The experience might feel personal, but the contours of the environment are completely new. The 1.0 versions—phones; video games—already hint at the attentional lag between technology and reality. What happens when we truly enter new worlds, ones in which we have no free will because the environment was never shared to begin with?

A young gamer wearing virtual reality (VR) goggles plays in a mock city set-up at a newly opened VR park at The Dubai Mall on March 6, 2018. (Photo by Giuseppe Cacace/AFP/Getty Images)

Recently a close friend bought a new gaming system. At one point, when we were walking around outside, he started laughing. For a moment he thought he noticed a mushroom that would give him a few points. He even took a step in its direction to pick it. The simulated world became part of his direct experience even though his immediate environment did not offer what he believed to be part of it. The more immersive our technologies become, the harder it will be to pull ourselves out of them.

In Understanding Media, McLuhan quotes the poet, W.B. Yeats: “The visible world is no longer a reality and the unseen world is no longer a dream.” This idea might seem new as we approach a world dominated by A.I. and virtual reality, yet it’s long been part of our experience. Our imagination has long offered new and strange worlds, yet in some way we are always in control. As other minds construct our environments, what will be left of us?

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Facebook and Twitter.