Researchers Track Unemployment Trends Using Cellphone Data

There’s much someone could glean about a person when they have their personal data in-hand. Even the metadata — where we go, how long we go there, and what we type into Google search — can say a lot. But what could someone do with just phone data? Apparently, quite a bit. As a team of researchers found a way to predict, with considerable accuracy, whether or not someone recently lost their job, using calls as a predictor.

The researchers wrote in their paper, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface:

“Here we present novel methods to detect mass layoffs, identify individuals affected by them, and predict changes in aggregate unemployment rates using call detail records (CDRs) from mobile phones.”

In the first part of the study, the researchers “[used] data already passively collected from mobile phones.” The calls were placed out of a plant in Europe that closed down in 2006. The researchers were able to use the cellphone data collected by three towers, which included all the calls made by individuals from this plant before and after the plant shut its doors. (A bit creepy.)

They wrote:

“Users highly suspected of being laid off demonstrate a sharp decline in the number of days they make calls near the plant following the reported closure date.”

From this data they were able to see some interesting trends in usage. For instance, “The total number of calls made by laid off individuals drops 51 percent and 41 percent following the layoff when compared to non-laid off residents and random users, respectively.”

“The number of outgoing calls decreases by 54 percent compared to a 41 percent drop in incoming calls (using non-laid off residents as a baseline). Similarly, the number of unique contacts called in months following the closure is significantly lower for users likely to have been laid off.”

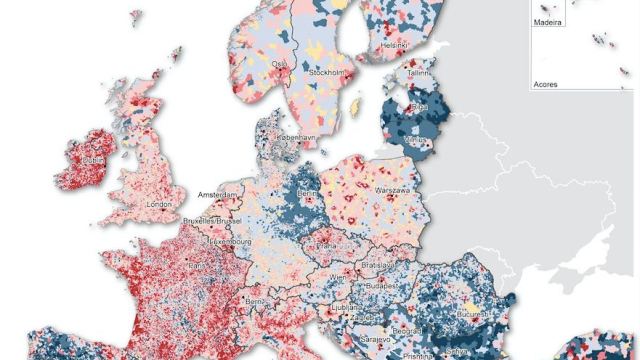

The researchers then used this data as a way to predict rising unemployment rates on a larger scale — in provinces. As to why the researchers used this method of collection rather than surveys, they argued that “surveys can be slow to collect, costly to administer, and fail to capture significant segments of the economy.” They also noted that they can suffer limitations of size.

The researchers make a fair point that using cell data is more efficient than traditional collection methods. But is it right? If anything, this study shows how dangerously accurate metadata can be. Brad Templeton, a board member of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, would agree, as he argues that we’re all a part of a surveillance apparatus that’s beyond what George Orwell could have imagined.