Dream hacking: Is this the dystopian future of advertising?

- Scientists have shown that it’s possible to “incubate” our dreams with basic ideas using auditory stimuli.

- They worry that marketers could make use of ubiquitous smart technologies to advertise in our dreams without consent.

- Dream-altering technologies could be used for good, as well, making it imperative to adhere to basic ethical principles.

Now that our homes are littered with “listening” smart devices and we are inseparable from our phones, it can seem like sleep is the only part of our lives that is off-limits to marketers trying to influence us. But this blissful bedtime bastion may not hold out much longer. In 2021, a team of 38 experts in the fields of sleep and dreaming signed onto an opinion piece warning that dream advertising is on the way.

It makes sense that marketers would seek to access our dreams. Warranted or not, dreams have special meaning for millions of people. Dreaming is when our brains can form strong associations.

“Dreams are actual mechanisms that have evolved biologically to help us make critical decisions about how to lead our lives in the future,” Robert Stickgold, a Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, an expert in dream studies, and lead author of the opinion piece, told NPR.

The American Marketing Association New York’s 2021 Future of Marketing survey of 400 marketers from various U.S. firms found that three-quarters aim to deploy dream advertising technologies by 2025.

But is this just typical marketing hype, or a candid recognition of an approaching dystopian reality?

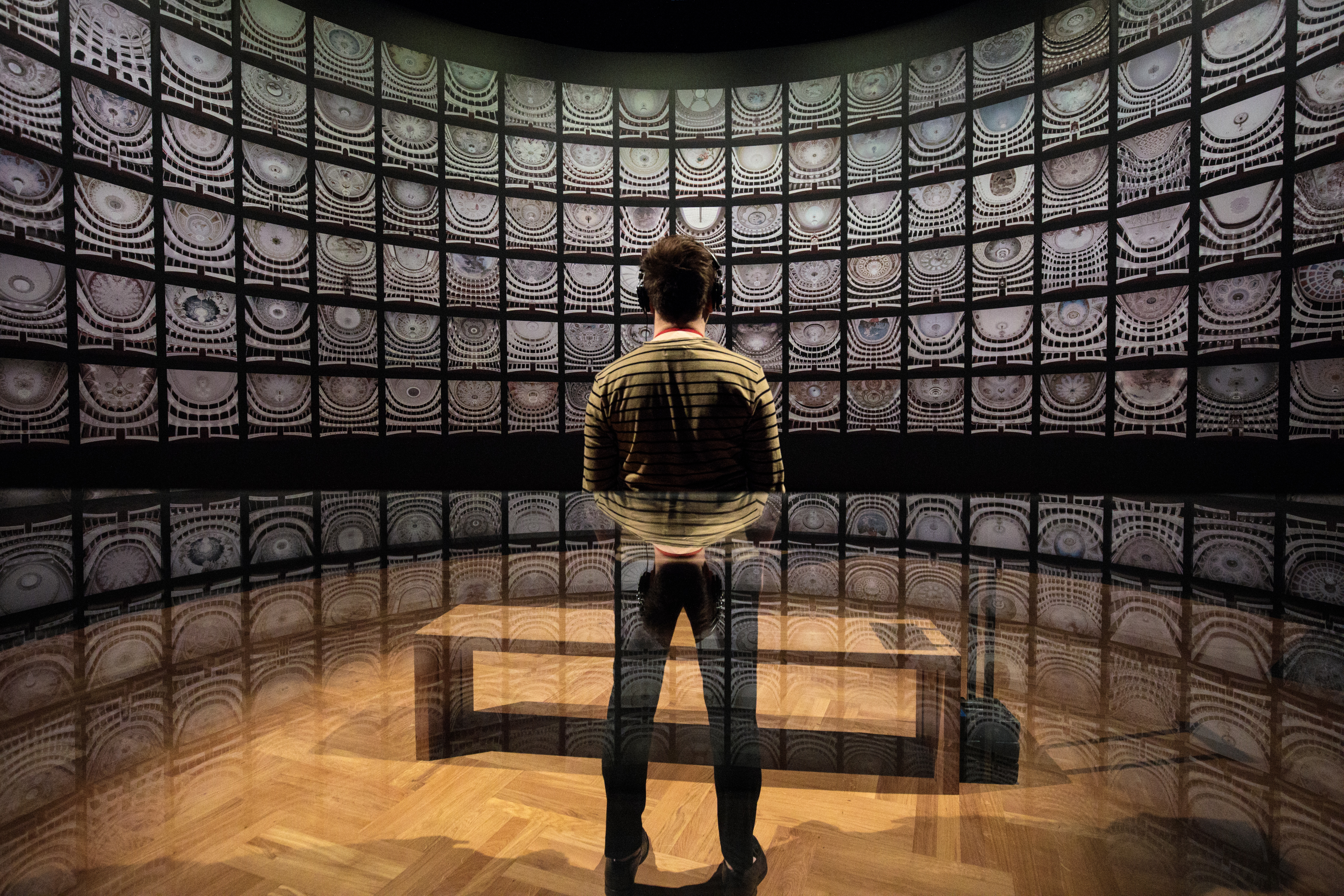

In the lab, scientists have already pioneered methods of altering the content of our dreams, albeit in a very basic way. In 2020, Adam Haar Horowitz, a PhD student in the Fluid Interfaces group at MIT, used a novel device called Dormio to “incubate” subjects’ dreams with basic ideas. The system detects when a wearer enters hypnagogia, the transitional state of consciousness between wakefulness and sleep, then plays them specific auditory stimuli with the aim of altering their dreams. In Haar’s published study on Dormio, he and his co-authors successfully used the system to make subjects dream about trees.

Now, Dormio and “trees” are a long way from realizing fully-formed dream advertising, perhaps the ultimate form of “product placement.” Still, the ubiquity of microphones in the bedroom raises a disturbing, albeit unlikely, possibility:

Most of us have smart devices on our wrists or at our bedsides as we sleep. These easily could be used to subtly initiate dream advertising. Imagine waking up to your phone emitting the enticing sounds of a carbonated beverage filling a cup, and a faint voice whispering, “Coca Cola…” The reason this is unlikely is because such messaging would constitute a blatant violation of consent and privacy, and thus would be quickly quashed in courts when discovered.

Ethics of dream hacking

Still, to prevent companies from even contemplating this sort of strategy, Stickgold and Haar insist policy steps should be taken soon.

“We believe that proactive action and new protective policies are urgently needed to keep advertisers from manipulating one of the last refuges of our already beleaguered conscious and unconscious minds: Our dreams,” they wrote.

After all, the same technologies — intimate implants and futuristic wearables — that could be used for dream advertising could also be utilized for more noble aims. “We envision that nightmare treatments, learning enhancements, overnight therapy, augmentation of creativity, and overcoming addiction are all within the realm of possibility,” Haar wrote with fellow researchers Pattie Maes and Michelle Carr.

But first, scientists and technologists should adhere to some basic ethics, they say: do not incubate dreams without consent; design tools that won’t result in dependency; and minimize impact on sleep quality.